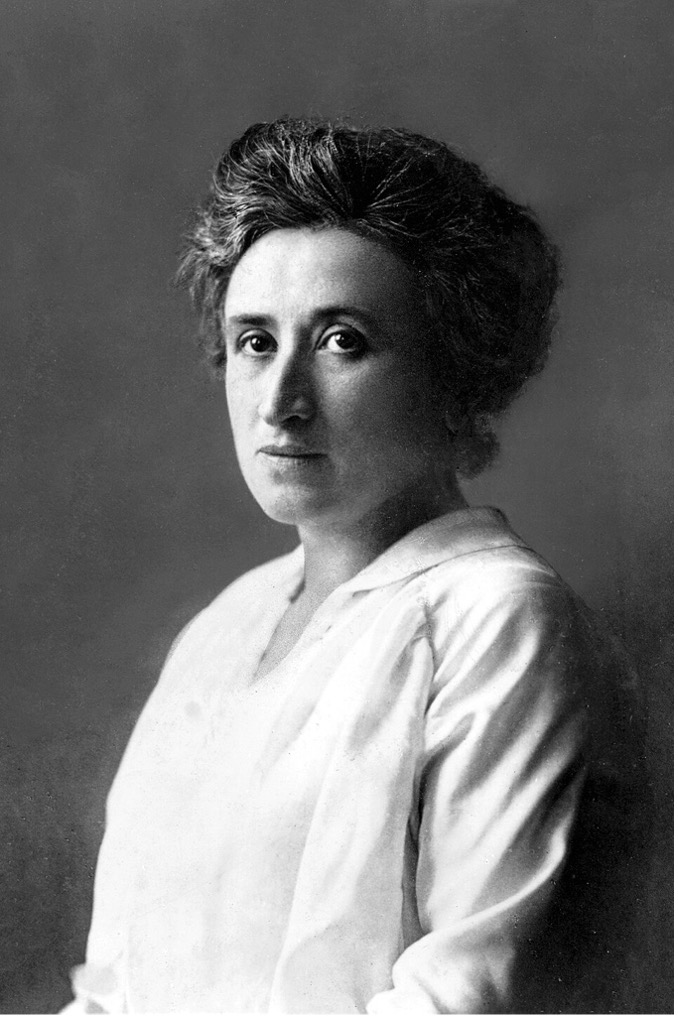

Rosa Luxemburg

A Woman of Dissent

Shaping left-wing politics and writing numerous political papers, her name is familiar to many: Rosa Luxemburg. After growing up in Poland, she pursued a broad and interdisciplinary education. Alongside other subjects, she attended law courses and earned a doctorate with a dissertation on Poland’s industrial development. Following her academic years, she began a political career in Germany – a career that would infamously come to a brutal end.

© Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Childhood and education in Congress Poland

Rosa Luxemburg was born as Rozalia Luxenburg in Zamość, then part of Congress Poland within the Russian Empire. “Rosa” was a nickname she chose for herself, and the spelling “Luxemburg” likely originated from a typographical error that she eventually adopted. Her birth certificate states December 25, 1870, but she celebrated her birthday on March 5 and claimed 1871 as her year of birth. The youngest of five siblings, she grew up in a Jewish household with well-educated parents.1) Her father wanted to secure a better education for his children, and therefore, the family moved to Warsaw when Luxemburg was two years old. A few years later, when she was five, she suffered from a diseased hip. A misdiagnosis of that disease left her with a lifelong limp. While in recovery, Luxemburg taught herself how to read and write. After being homeschooled by her mother, she attended high school in Warsaw. She showed linguistic talent from an early age and spoke Polish, Yiddish, Russian, German, English and French as an adult.

© National Library of Israel, Schwadron collection, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Already during her school years, Luxemburg was involved in socialist politics.2) Despite being top of her class in high school, she was denied prizes because the school administration became aware of her political stance. She was particularly active as an agitator in school and student circles. As police pressure intensified and threatened her with arrest, she left Congress Poland in 1888.3)

Studies across disciplines

Luxemburg moved to Zurich, where she was able to study at the University of Zurich – one of the few universities at the time that admitted women. In Germany and Austria, for instance, women were only granted access to universities around 1900. She began her studies in Zurich in the Mathematics and Natural Sciences Department within the Faculty of Philosophy. After attending courses in zoology and microscopy, she turned toward economics and eventually moved to the Faculty of Law.4) She was also politically active in Zurich. Together with Leo Jogiches, a fellow student and her partner at the time, she helped found a Polish Marxist party in Congress Poland. They also jointly published the magazine Sprawa Robotnicza (“Workers’ Cause”), for which Luxemburg wrote articles under the pseudonym R. Kruszyńska.

Luxemburg first earned the title “Doctor juris publici et rerum cameralium” which, according to the university’s examination regulations, required one written examination in constitutional law and another in economics.5) In March 1897, she submitted her dissertation titled “The Industrial Development of Poland”, which she described as a socialist thesis. Shortly thereafter, she entered into a sham marriage with Gustav Lübeck, a German national, and moved to Berlin in 1898 with her newly acquired German citizenship.

Political rise in Germany

Only days after arriving in Berlin, Luxemburg contacted the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany). At that time, she was already determined to play an important role in the party through her active involvement.6) She soon attended party and international congresses, where she became known for her passionate speeches. At the Stuttgart Party Congress in 1898, for instance, she declared:

“The only means of force that will lead us to victory is the socialist education of the working class in the everyday struggle.”

Luxemburg also wrote numerous articles for the newspaper „Leipziger Volkszeitung“, a daily newspaper of the labor movement in the German and international social democratic movement, and later served as one of its editors.

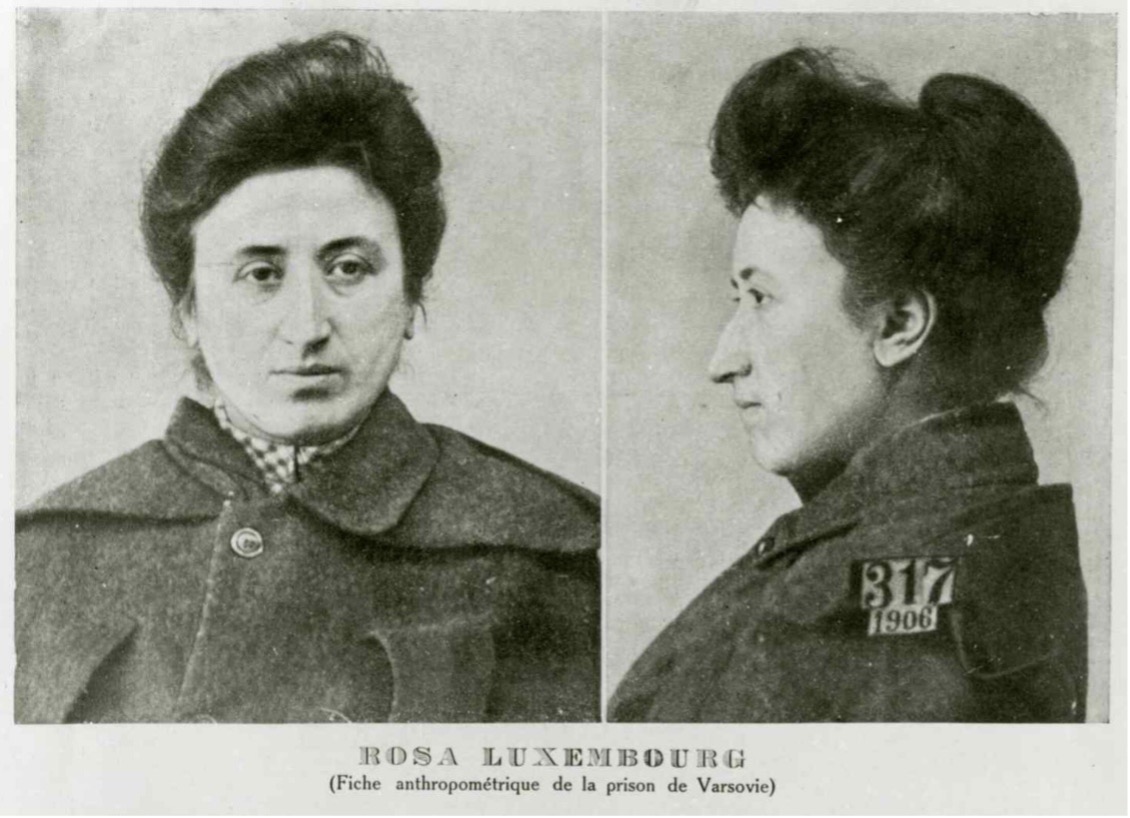

Advocacy for the labor movement, however, came at a cost. Luxemburg was arrested several times for her political activities and served her first prison sentence in 1904. After Kaiser Wilhelm II claimed that he understood the problems of the workers better than any Social Democrat, Luxemburg responded in a campaign speech: “The man who speaks of the fine secure existence of German workers has no idea of the facts.” She was subsequently sentenced to three months in prison for lèse-majesté. In 1906, she served another prison sentence, this time for “provoking class hatred”.

© Warsaw police, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Soon after, a new opportunity emerges: from 1907 onwards, Luxemburg taught economics at the SPD party school in Berlin. She found great joy in teaching and became a very popular teacher, while also being the only woman on the teaching staff. 7)

Between solidarity and critique of the women’s movement

Being the only woman was a role that Luxemburg often found herself in, notably at party meetings. Nevertheless, several distinguished women’s voices were present in the SPD at that time. One of them was a close friend of Luxemburg, Clara Zetkin, a prominent women’s rights activist who, among other things, initiated International Women’s Day. Luxemburg herself, however, was not active in the women’s movement and wrote next to nothing about women in the numerous political texts she published. In certain debates, however, she did comment on the issues of women. Luxemburg was in favor of women’s suffrage and gave a speech in Stuttgart in 1912 on “Women’s Suffrage and Class Struggle,” in which she strongly criticized the lack of women’s rights under the slogan “Give us women’s suffrage!” (“Her mit dem Frauenwahlrecht!”). In general, however, she showed little interest in the women’s movement, and instead advocated for the Social Democratic labor movement, in which, according to her, everybody should work together toward the same goals – regardless of gender. She believed that the women’s movement distracted from the class struggle and saw an independent women’s movement as a threat to the unity of the working class.

When revolution turned deadly

Shortly before the outbreak of World War I, Luxemburg was arrested in 1914 for giving anti-war speeches. In one of these speeches, she declared:

“If we are asked to raise the murderous weapons against our French and other brothers, then we cry: We will not do it!”

Despite her imprisonment, she remained politically active, writing numerous letters to her allies and composing several publications. In 1914, after the SPD agreed to grant the government war credits, Luxemburg and several party allies founded the “Gruppe Internationale” in opposition to this decision. One of these allies was Karl Liebknecht, a fellow member of the SPD who, like Luxemburg, was arrested for giving anti-war speeches. Over time, the group renamed itself the “Spartacus League” and joined the USPD (Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany) in 1917, forming a subgroup within the party.

With only brief interruptions, Luxemburg was held in various prisons until the end of the war. During this period, she also wrote the text “The Russian Revolution,” in which she criticizes the Bolshevik Revolution and which contains one of her most famous quotes:

“Freedom is always freedom for those who think differently.”

She was released from prison in November 1918. At the turn of the year 1918/1919, the Spartacus League and other communists founded the KPD (Communist Party of Germany), with Luxemburg presenting the party program. A few days later, the so-called Spartacus Uprising took place, in which the communists around Karl Liebknecht and Luxemburg attempted to prevent free National Council elections and instead establish a council republic, a system that aimed to give political power directly to workers’ and soldiers’ councils. The uprising was suppressed by government‑backed Freikorps units. Luxemburg and Liebknecht, who had gone into hiding, were captured, interrogated and killed by Freikorps soldiers on 15 January 1919.

Legacy and memory

Luxemburg’s death was met with widespread grief and outrage. To this day, her life and death continue to be commemorated.

© Lupus in Saxonia, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons,

The foundation affiliated with Die Linke (German Left Party) bears Rosa Luxemburg’s name, making her the only woman among the namesakes of Germany’s political foundations. Her writings continue to be widely quoted and discussed. At the same time, there is now greater awareness of the extent to which she is viewed through a mythical lens. What remains beyond dispute, however, is the depth of her political influence: through extraordinary intellectual and personal commitment, and as a woman in a profoundly male-dominated era, Rosa Luxemburg stands as one of the true pioneers of her time.

Further Sources

- Rosa Luxemburg or: The Price of Freedom Published by Jörn Schütrumpf

- Rosaluxemburg.org/en/

- Digitale Edition der Schriften von Rosa Luxemburg

- Eleanor Penny, Who Was Rosa Luxemburg?. Novara Media

- Podcast: tl;dr #1: Rosa Luxemburg – Sozialreform oder Revolution? (Alex Demirović, Miriam Pieschke)

- Podcast: HerStory von Jasmin Lörchner: Rosa Luxemburg: Blick hinter den Mythos (mit Ralf Grabuschnig von Déja Vu Geschichte)

- Podcast: BBC In Our Time Rosa Luxemburg

References

| ↑1 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 25. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 48. |

| ↑3 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 51-52. |

| ↑4 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 58-61. |

| ↑5 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 96. |

| ↑6 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 144. |

| ↑7 | Piper, Rosa Luxemburg. Ein Leben, p. 329-330. |