“Almost Genocide”

Accountability and the Emergence of Intent Over Time

In a valuable recent post, Kai Ambos and Stefanie Bock reflect on the unfolding situation in Gaza, and on whether Israel’s actions may constitute genocide as a matter of international law. Their piece is a laudable and direct assessment of a question that many are asking, but, at least in Germany, retains a quasi-taboo status. They find that it is more probable than not that Israel’s actions amount to genocide. In other words, one might say that they think of the situation in Gaza as an “almost-genocide”, moving ever-closer to genocide, as time goes by. In the short post, they clearly and skilfully encapsulate the components of a debate that has been going on for months.

The following post takes the Ambos and Bock post as a point of departure, but does not directly engage the doctrinal question the authors explore. My purpose, rather, is to examine the underlying assumptions of their observation: what initially did not look like genocide now probably does. While it is not difficult to see how the material element of violence is expanding and becoming more egregious with the passing of time, slightly more confusing is the transformation of intent into the “specific intent” attached to the prohibition of genocide. I focus on the latter issue.

This post proceeds in six parts. Section 2 examines how genocidal intent can emerge over time. Section 3 challenges the volitionist assumption that intent must precede action, drawing on phenomenology to show how circumstances can not only reveal but also constitute mental elements. Section 4 explores the political dimensions of temporal identification in the Gaza case. Section 5 argues that forward-looking analysis is essential to prevent accountability from becoming an ever-receding horizon. Part 6 concludes, reflecting on implications for the ICJ’s approach to intent in South Africa v. Israel and the preventive function of genocide law.

The Emergence of Genocidal Intent

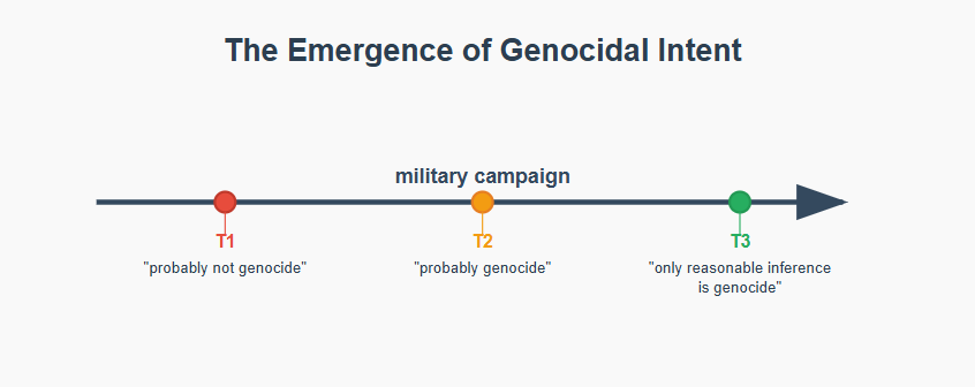

Ambos reminds us that at an earlier stage (let’s call it T1), he did not believe a legal analysis of Israel’s actions would meet the threshold of genocidal intent (19.1.24). Currently, however (T2), he and Bock have come to believe that “the dynamics of the conflict now speak more in favour of genocide than against it” (6.4.25). Thus, Ambos and Bock conclude: “While it was relatively easy to dismiss […] the genocide claim in the first few months of this Gaza war invoking the high threshold of the intent to destroy, this becomes more difficult with each day this war continues in this brutal and disproportionate manner.”

Focusing specifically on the question of genocidal intent, it may be useful to distinguish two interlinked questions that this timeline of transformation raises:

- Could both Ambos’s assessment in January 2024 (T1) and the authors’ joint assessment in June 2025 (T2) be correct for their own times?

- Can genocidal intent itself change over time? Can a state that lacked such intent at T1 come to possess it at T2?

As for the first question, it may be solved relatively easily, even without a theory of the transformation of the underlying state intent. Such a solution would assume that genocidal intent probably existed all along Israel’s response to Hamas’s horrendous attack on October 7. While Ambos initially did not identify it, other legal experts did see what was coming. Surely, this is the argument that lawyers who submitted the application in South Africa v Israel have made. Perhaps they had their ear closer to the tracks and so could hear the train coming. According to this view, the reality of genocidal intent is consistent. Ambos was simply wrong in T1. (I should already say that I similarly believe the genocidal intent emerged with time).

But the second question is more interesting and does require a theory of the emergence of intent over time. Stated simply, it is whether and how intent can transform from non-genocidal to genocidal. This question touches upon perhaps the most basic legal question about genocide: what is the requirement of “specific intent” (dolus specialis)? And how is it illuminated by the evolution of intent? I believe there might be a risk, conceptual and practical, that doctrine will try to gloss over this evolutionary aspect and try to treat genocidal intent as necessarily fixed and internally coherent.

The latter approach would falsely assume that genocide, once committed, must have been the plan all along. Conversely, it would hold that if Israel’s intent was not genocidal at T1, it cannot (or is very unlikely for it to) become genocidal at any subsequent moment during a campaign; I believe, contrary to some commentators, that the attack on Gaza initially had a legal justification. Even if it was not wise to attack Gaza before negotiating a hostage deal, there was no legal imperative not to do so after the Hamas attack of October 7, 2023.

Furthermore, it is almost certain that—assuming they will continue to partake in the process – Israeli lawyers will emphasize such an argument before the ICJ in South Africa v Israel. They will highlight the initially justified moment of the Israeli campaign and argue that the entire following attack needs to be interpreted in its light. But the latter “entailment” would be a sleight of hand, and the ICJ should reject it.

Genocidal intent does not necessarily pop, prefabricated, out of the perpetrator’s state’s head. It emerges – gradually, often unevenly – as a product of action, omission, emotion, and political opportunity. A war that once had legal justification as defence can thus harden into something else: the destruction of a group as such. This is as true in the specific conditions of Gaza, as it is as a matter of principle.

Beyond Volitionism

In terms of an intuitive theory of action—one that resonates with much of general criminal law—we often assume that intent (mens rea) comes first, and the act (actus reus) follows. In philosophical terms, this view is sometimes described as volitionism. The sequencing between intention and action seems to work fine in many ordinary contexts. I plan to buy a train ticket and complete the transaction to purchase it. I reserve a seat for dinner and then go out and sit at the table. As Scott Shapiro has observed, law in general is very much facilitating plans.

But situations where genocidal intent emerges in the course of war help illuminate why volitionism should ultimately be rejected. In such cases, action often precedes intent. The first shots might, for example, aim not only at defence but also at collective revenge; but not necessarily rest on a genocidal plan. But this may create the conditions in which further action becomes possible. Of course, in the jurisprudence of international courts, genocide frequently does involve a “plan” (see e.g. Jelisic, [Appeals Chamber], July 5, 2001, para. 48). I take no issue with that idea. But it is important to remember that the plan itself evolves in reaction to national security conditions and shifting political circumstances.

Indeed, the ICJ’s “only reasonable inference” test already allows for inferring intent from patterns of conduct over time. What it doesn’t squarely capture is the way in which circumstances can constitute the mental element of a state plan. What this means is that, from a certain perspective, the volitionist order should be reversed: the actor acts, and the intention emerges from what the (first) action revealed, enabled, and constrained. This applies to individual actors, but perhaps even more so to non-natural persons such as states, who do not really have a mind to speak of. A legal framework that insists on a fully formed mental element at the outset will fail to grasp the process through which genocidal intent—or state intent more generally—becomes real. As highlighted above with view to Israel’s likely argument, such a framework may very end up being an argument that a state responsible for genocide puts forth to evade accountability.

Within philosophy, the tradition of phenomenology has revealed how intentions do not necessarily precede action, but arise from how agents are practically involved in the world—through use and interaction. Phenomenology thus relativizes the primacy of the mental state of direct consideration of an object: what John Searle called “aboutness”. In the phenomenological view, intention is not static but historically situated and experientially formed in the everyday.

Lawyers may suspect that such a turn away from volitionism reduces our ability to pass judgement on action and undermines accountability. It may even be deemed to relativize moral standards. But I don’t think this is true. Jewish religious law scholars have famously recognized that our embeddedness in unchosen conditions coincides with our ability to decide for ourselves: “All is foreseen, and freedom of choice is granted.” Whether for Israel or, potentially, for Hamas fighters, accountability should never be an exercise of de-contextualization.

The Politics of Recent History

Can we pinpoint when, exactly, to locate T1 and T2, in the case of Gaza? In other words, can we determine when the reality of Israel’s campaign transformed from “probably not genocide” to “probably genocide”? Was T2, for example, on May 6 2024, when Israel began its offensive on Rafah, despite allies’ protestations, and President Biden’s warning? Or was T2 on February 5, 2025, when Netanyahu and Trump stood in the White House and declared a plan of occupation and mass deportation? Many other moments along the way may come to mind.

This, of course, is not only a descriptive question. The answer any one of us may give will be deeply entangled with our moral and political judgement. Indeed, for those of us who believe that we can identify probable genocidal intent, where we locate T1 and T2 may function as a kind of litmus test for our moral and political preferences. The identification of transformations may reveal how we think about state violence, civilian vulnerability, and the permissible thresholds of military conduct – with regard to a particular case, or generally.

Ambos and Bock describe a directionality between T1 and T2. In doing so, they inadvertently allude to this normativity of timing, even if not explicitly. Interestingly, however, they stop short of asking what it would take to reach T3 – the point, for it is still in the future – when genocide will become more than just probable. T3 stands for the moment when the Israeli military campaign will meet the ICJ’s famous test from Bosnia v. Serbia, according to which “the only reasonable inference” is the commission of genocide (see figure).

Contrary to commentators who believe Israel’s campaign was genocidal from the start, I am with Ambos who identified T1 in the first months after October 7. Contrary to Ambos and Bock, I believe T3 is also already in the past, or in other words, that Israel is committing genocide.

The Ever-Receding Horizon of Accountability

While Ambos and Bock do not do so, for those who believe we have not yet reached T3, it is important to articulate the necessary and sufficient conditions for getting there.

Looking from T2 only backwards and never forwards to T3 risks creating an ever-receding horizon of state responsibility. If this is true, we will always remain in the asymptotic curve of “almost genocide” and never enter the territory of full-blown “genocide”.

This dynamic is familiar. In the case of the charge of apartheid, scholars and other commentators, including several prominent Israeli politicians, have for years acknowledged that Israel is “approaching” the threshold. A permanent occupation has solidified structural racial or ethnic discrimination. The intent had clearly been emerging. And yet the conclusion remained forever deferred—always “not yet.” This constant “almost” may remind us of the way we regard ourselves, or perhaps a good friend. We or they may clearly be falling down a dangerous path; but we may not be ready to confront that reality. We keep warning, until “it is too late”.

A version of this almost-apartheid reasoning appeared recently in Judge Georg Nolte’s separate opinion in the Advisory Opinion of July 19, 2024: As Florian Jeßberger and Kalika Mehta explain,

“the Court did not have sufficient information to establish the subjective element (the specific intent to establish and maintain an institutionalised regime of domination and oppression by one racial group over the other) on the part of Israel. In his view, the purpose of domination should be the ‘only reasonable inference’ from the conduct of Israel to satisfy the specific intent to constitute apartheid. In this case, he noted that Israel may also be motivated by security considerations and/or driven by the aim of asserting sovereignty over the West Bank.”

Even now, when Israel has arguably embarked on an even more egregious plan, the leader of the Israeli “Democrats” party, Yair Golan, is warning that Israel is in the condition of almost apartheid.

Without a forward-looking framework, legal accountability turns into a mirage: always visible, never reachable. Among the assumptions this perpetual “almost” is some lawyers’ fixation on volitionism: the failure to interpret legal intentions from objective circumstances. This, rather than a departure from volitionism, is what truly threatens our ability to pass judgment and uphold normative standards.

To be sure, however, the move beyond volitionism that I suggest is not intended to expand the notion of genocide or increase the number of cases in which we conclude that genocide has occurred. Indeed, “positive” state actions can, just as well, help reduce the genocidal light in which previous statements of state officials should be interpreted. In this case, such actions may include bona fide provision of humanitarian aid, or a stable ceasefire agreement. The latter remains true as long as a state has not reached T3, from which it may be more difficult to roll back the need for accountability.

What remaining conditions could move us into T3, if Ambos and Bock would choose to specify them?

Many of the obvious candidates are already behind us: sustained mass displacement of the civilian population without plans for return; deliberate and mass destruction of essential infrastructure and homes; recurring statements from officials framing the entire population as an enemy; refusal to allow humanitarian assistance, or a predictably failed distribution system, even when civilian starvation becomes acute; recurrent firing on seekers of that aid. That Israel’s attack has met such conditions has led me to believe that T3 is already indeed a fait accompli.

One can only surmise that, for other commentators who are not there (yet?), a remaining “smoking gun” may be readily available after a Hamas surrender. If Hamas is dismantled or rendered militarily inactive, and the campaign of destruction continues, they too will have to arrive at the conclusion that genocide is “the only reasonable inference.” At that point – when the declared objective of the war is attained and destruction proceeds nonetheless – they will have to change their mind. It would no longer be plausible to read the campaign as a war for national security.

But this narrow understanding of the necessary remaining condition is in some tension with Ambos and Bock’s final note, which I strongly agree with: that “genocidal intent may well coincide with other motives, e.g. certain military objectives or security policy considerations.”

Conclusion

The openness Ambos and Bock display to an emergent notion of intent is a major, if not fully articulated, contribution of their post. They capture something important in their underlying observation that state intent can change over time. A military campaign that began as legal may, given particular circumstances, transform into a genocide.

This is likely going to be explicitly or implicitly denied in Israel’s concluding arguments before the ICJ in South Africa v. Israel. For the ICJ, it is crucial to remember that intent may emerge over time. The idea moves us beyond a static legal imagination – an inheritance of volitionism – and toward an analytically and phenomenologically grounded account of intent, including genocidal intent.

And yet, it is regrettable that the authors do not take up the forward-looking aspect of the emergence of genocidal intent. As is well known, the Genocide Convention is not only retrospective. It requires states to act to prevent genocide when the risk becomes evident—before the threshold is crossed. If intent is not binary but developmental, then prevention must be sensitive to the emergence of genocidal intent. Measures that aim to ensure accountability cannot wait until genocide has become fully legible in hindsight.

To some extent, the ICJ has already reflected this insight in its indication of provisional measures. That provisional measures short of a ceasefire may not have been truly preventive was a predictable outcome. But the issue is not only one of enforcement power, it is also conceptual. By identifying the emergence of genocidal intent without asking what it would take to name genocide’s arrival, we may ultimately miss the preventive function of the Genocide Convention.

Of course, some of us already believe that we can identify T3 – the full emergence of genocidal intent – in the past, not in the future. But even within this group, disagreement remains. Some may believe that genocidal intent was always there (denying T1). Others, me included, may have identified an initial moment of legal justification for war, now long gone.

When the day comes in some years, assuming the ICJ majority does not accept that Israel’s campaign was genocidal from the outset, the court will need to determine whether and when genocidal intent—T3—emerged. For doctrinal and political reasons, the February 2025 announcement of a mass deportation plan, later reiterated by Netanyahu in May, offers a compelling candidate: the plan was unimplementable, yet the military campaign has continued under its pretext. It thus became impossible to justify the ongoing destruction as a matter of national security.