The Plan to Abolish Asylum

From Protection to Fiction

The German title of Peter Høeg’s novel Der Plan von der Abschaffung des Dunkels (The Plan to Abolish the Darkness – English title: “Borderliners”), which lends this editorial its title, describes a system that seeks to improve people by controlling them. At first glance, this has little to do with the German constitutional right to asylum. That right appears unshakeable: anchored in the Basic Law as a lesson drawn from the mass persecution and murder perpetrated by Nazi Germany against its own citizens, grounded in the conviction that states must not close their borders when people flee for their lives.

Yet in everyday politics we are witnessing the abolition of asylum without formally repealing the right to asylum. The right itself remains in place as a symbolic guarantee, while access to it is systematically curtailed – and in part obstructed – by rigid measures.

From right to exception

Asylum was the moral essence of the post-war era: “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution,” declares Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This claim is legally enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. The lesson of the concentration camp system in general, and of the Shoah in particular, taught us that the right to asylum is meaningless if it cannot be accessed (“to seek”) or if it does not entail enforceable entitlements (“to enjoy”). It also requires procedural realisation: a right to a fair and efficient process. Based on these considerations, the Basic Law states: “Persons persecuted on political grounds shall have the right of asylum.”

Political discourse, however, increasingly embraces a different understanding: the right to refuse asylum, which is allegedly necessary for reasons of sovereignty. For years, German and European asylum policy has been increasingly focused on the art of obstruction. While the legal entitlement remains on paper, it is hollowed out through procedural barriers, fictional allocations of responsibility, and political myths. The so-called “asylum compromise” between CDU/CSU, FDP and SPD in 1992 is emblematic: since then, any asylum application has been deemed inadmissible if the applicant entered Germany via a safe third country. In this way, the constitutional guarantee was largely dismantled through procedural manoeuvres – while politicians continued to profess their commitment to the individual right to asylum. This discrepancy between formal protection and practical (in)accessibility is not a side effect, but the defining pattern of present time.

Access to protection beyond the Basic Law

Despite this procedural hollowing-out, in practice, Germany has so far not drastically curtailed refugee or humanitarian protection. Protection continues to be granted within asylum procedures – though largely on the basis of international, European, and EU-derived law incorporated into domestic law. With the implementation of the EU’s Common European Asylum System (CEAS), itself grounded in the Refugee Convention, distinctions between protection statuses have largely vanished. In most cases, beneficiaries can indeed “enjoy” the rights attached to their status. To this day, people seeking asylum in Germany generally have de facto access to a substantive examination of their protection needs.

Dublin Procedures and CEAS

This access is often delayed by a preliminary procedure for determining responsibility (the “Dublin procedure”). Despite symbolically charged rejections at Germany’s internal Schengen borders such access has not (yet) been systematically refused. In these cases, applicants are often not transferred to the state determined as responsible. Therefore, political debate frequently brands the system “dysfunctional”. This widespread – and incorrect– notion obscures questions of fairness. Contrary to common assumptions, Germany, for instance, has not received an excessive number of asylum applications when measured against its economic capacity and population size, as this week’s EU migration report shows.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Vier Promotionsstellen im Verfassungs-, Unions- und Völkerrecht

Interesse an einer Promotion zu aktuellen Fragen des Verfassungs-, Unions- oder Völkerrechts?

Für das Europa-Institut, insb. am Lehrstuhl für Öffentliches Recht, Europarecht und Völkerrecht – Prof. Dr. Till Patrik Holterhus, MLE., LL.M. (Yale), Direktor des Europa-Instituts – sucht die Universität des Saarlandes ab dem 01.02.2026 vier verantwortungsvolle, motivierte und engagierte wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiter:innen (50% TV-L E13; 3 Jahre).

Bewerbungsfrist: 28.11.2025

Alles weitere hier.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The European Commission has drawn on this alleged dysfunction in pushing for CEAS reforms. At least since the 2016 proposals, the focus on preventing access to substantive asylum procedures has intensified. The reforms target asylum migration from border states to the centre of Europe (so-called “secondary migration”). This has given some reason to claim new legitimacy when calling for restricted access to asylum. Its most visible manifestation can be found in the reinstatement of internal border controls designed to prevent such movements.

The reformed CEAS, due to be applied from mid-2026, likewise reflects many tendencies toward abolishing asylum. Again, without erasing protection norms; instead, it erects legal and practical barriers to accessing them. Because internal redistribution of asylum seekers among EU Member States is met with little approval among the states called upon to shoulder responsibility, national and European actors have intensified efforts to construct “safe third countries” and to externalize responsibility. For many European governments, the desired outcome would be a legal sphere in which the formal guarantee of asylum still formally exists while actual protection is provided elsewhere.

In such a system, a right that once embodied a collective moral commitment risks degenerating into a legal simulation.

The myth of the “migration turnaround”

Politicians currently like to speak of a “migration turnaround”. In reality, the turnaround occurred years ago and is reflected in hyperactive lawmaking that destabilises the legal system itself, along with its implementation. There have been more than one hundred amendments to residence and asylum law in the past decade. These changes are routinely presented as safeguarding the rule of law. In truth, where they do not address skilled migration, they primarily introduce further restrictions that produce a more rigid, distrustful system. A rule-of-law system that reinvents itself every few months loses its internal stability and trustworthiness.

This development follows a specific political logic. The media and political treatment of the “Cologne New Year’s Eve” events, together with European developments – notably the 2016 CEAS reform drafts and the so-called EU–Turkey deal of the same year – triggered a “migration turnaround” that has since intensified. Since then, German asylum law has maintained a state of permanent overcorrection. Each of the more than one hundred legislative amendments in ten years repeatedly promised to “restore order” and “control” and to achieve the “management and limitation of migration”. They aimed not only to facilitate deportations but also to curtail access to protection in Germany. Without examining the effects of previous reforms, new rules were continually enacted, often expedited in response to incidents of violence attributed to foreigners, or parliamentary debate. This simulation of decisiveness, with its exhausting chain of amendments, has almost completely overlooked the administrative authorities tasked with implementing the law. In essence, it is legal hyperactivity masquerading as governance. Asylum law becomes a product of exhaustion – intelligible, if at all, only to specialists. Anyone unable to navigate this thicket of procedures and access barriers stands little chance of obtaining protection. This is not collateral damage; it is part of the strategy.

A strategy not primarily aimed at remedying shortcomings, but at giving the impression of capacity for action – “doing something” about alleged loss of control, “illegal migration”, or alleged misuse. The result is a paradox in which the law becomes the vehicle of its own erosion.

Those who amend the law monthly do not strengthen the rule of law – they render it unrecognisable.

Rhetorical escalation

The rhetoric, too, has sharpened. Where debates once revolved around “implementation deficits”, now a “rule-of-law problem” is invoked. The shift is telling. The issue is no longer inadequate enforcement but supposedly lost “control” and imminent “security threats”. This rhetorical lever legitimises ever-new intrusions into the fundamental rights of people seeking protection, especially restrictions on substantive assessment of protection needs.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Wissenschaftliche*r Mitarbeiter*in (w/m/d) im Umfang von 30 Wochenstunden (75 %) an der Universität Erfurt, Professur für Deutsches und Europäisches Zivil- und Wirtschaftsrecht zur Unterstützung in Lehre und Forschung gesucht.

Weitere Informationen hier.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

As political language narrows to control, deportation, and deterrence, the notions of protection, humane reception, and the assumption of responsibility recede. Asylum is semantically absorbed into a security architecture oriented toward efficiency, border management, and symbolic toughness – often accompanied by experiences of violence for those affected. Ongoing internal border controls, pushbacks without access to the procedure, and sweeping exclusions from benefits are paradigmatic examples. They openly contradict EU law and decisions of both the CJEU and the ECtHR.

These violations are deliberate. They are not concealed but often hinted at or openly acknowledged – as a political message that Brussels, Luxembourg, Strasbourg, or Karlsruhe will not set the terms. The intention is to pressure these institutions into recalibrating their standards to political demands. This undermines the rule of law by denying the principle that state authority is bound by law. The breach becomes a performance of sovereignty – reflected especially in the disregard for the judiciary and the call for courts to adjust their standards to the perceived needs of asylum and migration policy.

When governments bound by the constitution systematically question and circumvent fundamental rights protections for one group, they jeopardise the rule of law itself. When the interior minister claims that current migration policy reflects what citizens expect, the criterion of law is replaced with the criterion of presumed public sentiment. Invoking supposed public expectations becomes a tool for bypassing or neutralising legal standards through moralising rhetoric.

Defending the law against its friends

The tragedy is that this erosion occurs in the name of the law. Those who deliberately blur the line between legality and legitimacy inflict self-harm on the rule of law. A democratic state may make mistakes, even fail. But a state that intentionally violates its own law and presents this as virtue damages the foundation of trust on which any legal order rests.

When migration policy accepts legal violations and relies on protracted litigation, the issue is no longer migration or asylum itself, but the integrity of the law itself. The abolition of asylum by obstructing access is, above all, a political project that not only tests the limits of the rule of law but consciously and systematically exceeds them. This is accompanied by a cultural shift within the legal sphere: as we grow accustomed to state violations of the law being legitimised as an alleged necessity, political rhetoric begins to reshape legal practice. When policymakers, authorities, and statutory frameworks conceptualise asylum seekers as persons “potentially obliged to leave”, this framing shapes decisions, files, and judgments – and above all the lived reality of those affected.

Asylum is the litmus test of constitutional democracy because it protects those with little-to-no political representation. Abolishing it does not eliminate refugees – it merely constricts their already fragile spaces of protection. Asylum determines whether the law withstands what is rhetorically framed as crisis and overload or whether it becomes mere scenery.

This erosion reaches beyond asylum law. Those who partially suspend the law at external borders and systematically block access to justice for certain groups within the country lose the moral authority to advocate or demand human rights standards elsewhere.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Transform your career with Loyola Chicago’s top-ranked LLM for International Lawyers, built on the core principles of academic excellence, affordability, and flexibility. Choose from 160+ courses taught by distinguished and engaged faculty, access tailored career support, and gain hands-on experience in the heart of vibrant Chicago, a major legal and financial hub. Loyola’s LLM empowers ambitious lawyers from diverse backgrounds to excel as ethical global leaders. Further information.

Curious? Attend Germany’s top LLM Fairs next week and meet Insa Blanke in person:

15. 11: e-fellows LLM Day in Frankfurt

17. 11: DAJV LLM Day in Köln

22. 11: e-fellows LLM Day in München

Further information.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In light of this, moral outrage – necessary as it is, and intended to speak to our emotions – must be paired with a renewed sobriety about the law. What offers a way out is not indignation at suffering but a steadfast insistence on the force of law, even when it proves uncomfortable. Asylum protects not only those who flee. As an individual right, it also safeguards the rule of law and democracy from themselves.

The loss of empathy as a legal problem

Something else is required as well – empathy, often dismissed by lawyers as a soft terrain, yet the foundation of every fundamental right. Asylum presupposes that we recognise the suffering of others as legally relevant. When empathy is politically discredited, the law loses its basis.

Contemporary asylum policy thrives on this refusal of empathy. It relies on distance and administrative neutralisation. Those who expand rules of responsibility and admissibility to the point where even the possibility of lodging an application becomes an odyssey evade their human rights obligations. In this sense, the gradual dismantling of asylum in Germany and Europe is not only a legal development but also an anthropological one. The debate seeks to reshape our image of asylum seekers. They are cast as dangerous rule-breakers; their individual circumstances and inherent need for protection are rendered invisible. This trend is more dangerous than any constitutional amendment. Protecting those with almost no voice requires law – and the rule of law – to remain stronger than the fear accumulated in the current migration panic.

The abolition of the dark

In Høeg’s novel, a system of rigid control attempts to eradicate darkness – only to create new, unavoidable darkness of its own. Much the same is true of German and European asylum policy. In attempting to impose order and security through rigid control, it obscures the very fundamental right it claims to protect.

*

Editor’s Pick

by VERENA VORTISCH

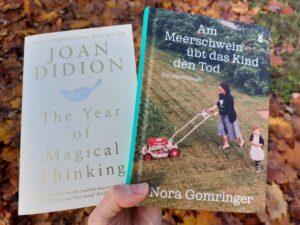

The autumn-winter bleakness is setting in (at least here in Berlin), making it the perfect time to turn, alongside the seemingly endless storms of political injustice, to the finiteness of all (human) existence and read Nora Gomringer’s Am Meerschwein übt das Kind den Tod (The Child Practices Death on the Guinea Pig). Subtitled “A Nachrough” (a bilingual wordplay with “Nachruf”, obituary), it recounts with humour, love, and bewilderment not only the loss of her mother, but also growing up with a famous father, depression, dealing with a family’s Nazi past, and, of course, the eponymous pets.

And while you’re at it, you might (re)read Joan Didion’s great The Year of Magical Thinking, which opens like this: “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant. You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends. The question of self-pity.”

*

The Week on Verfassungsblog

summarised by EVA MARIA BREDLER

Political rhetoric can carry real legal weight, as CONSTANTIN HRUSCHKA notes above. This is evident in Merz’s comment on the “cityscape”: he praised the falling number of migrants while pointing out that “there’s still this problem in the cityscape.” In their sociological analysis, AZIZ EPIK, HELENE HEUSER and NINA PERKOWSKI (GER) explain how Merz thereby legitimises exclusionary practices, arguing that the chancellor’s rhetoric produces the very insecurity it claims merely to articulate.

The cityscape also increasingly includes a new form of protest that does more than dissent – it actively prevents political participation. This raises a pressing question: when do demonstrations themselves pose a threat to democracy? WOLFGANG HECKER (GER) argues that such obstructionist protests cannot be justified and calls for the consistent upholding of democratic rules – especially at a time of rising attacks on the rule of law.

Democratic rules have now been tightened in Parliament. The Bundestag revised its rules of procedure, formalising some established practices while responding more sharply to provocations in the chamber. PATRICK HILBERT (GER) welcomes the reform, suggesting it could contribute to a more respectful debate culture.

Meanwhile, the European debate culture has had to deal with undemocratically elected members within its ranks. The European Parliament has now rejected Hungary’s request to lift the immunity of MEPs Péter Magyar and Klára Dobrev. ATTILA MRÁZ (ENG) sees this as the right decision, based on the wrong premises.

The European Union itself is facing accusations of undemocratic practices. It is increasingly using so-called omnibus legislation – a single, relatively fast vehicle for multiple legal changes. But at what constitutional cost comes that ride? ALBERTO ALEMANNO (ENG) warns that omnibus laws risk undermining transparency, evidence-based decision-making, and public participation in the lawmaking process.

These constitutional concerns are also a weekly preoccupation in the United States. Their Supreme Court recently heard a pivotal case: Learning Resources v. Trump and Trump v. V.O.S. Selections, Inc. examines whether Trump was allowed to use emergency powers to impose sweeping tariffs that functioned effectively like taxes. The Court faces a landmark decision on the separation of powers – one that lies at the intersection of two powerful, and potentially conflicting, trends in the Court’s recent jurisprudence, between limiting and expanding presidential authority. LORENZ DOPPLINGER (ENG) outlines the possible paths the Court could take and what is at stake for the US constitutional system.

Constitutional frameworks can also be undermined technically. In Hungary, a massive data leak revealed the personal information of nearly 200,000 citizens allegedly connected to an opposition app—including judges. Pro-government media immediately published their names, questioned their impartiality, and even called for dismissals. TOMÁS MATUSIK (ENG) traces what this doxing reveals about the fragile independence of Hungary’s judiciary.

In Poland, another hard-won achievement appears precarious: Prime Minister Donald Tusk has floated the possibility of Poland withdrawing from the European Convention on Human Rights. MAGDA KRZYŻANOWSKA-MIERZEWSKA, TOMASZ TADEUSZ KONCEWICZ, MARCIN GÓRSKI, MONIKA GĄSIOROWSKA and RADOSŁAW TYBURSKI (ENG) explain the risks and potential side effects.

Sometimes, however, the side effects are more promising than the intended outcome. In May, after years of litigation, the Higher Regional Court of Hamm issued its final ruling in Lliuya v. RWE AG, in which a Peruvian farmer sought to hold the German energy giant RWE financially responsible for measures protecting his property from a potential glacier flood. While the court ultimately rejected the claim, VERENA KAHL and EZIO COSTA (EN) expect synergies: the standards set regarding extraterritorial responsibility, causality, and preventive protection could strengthen transnational climate litigation and contribute to climate justice across the North–South divide.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

An der Rechtswissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Wien ist eine Tenure Track-Stelle für Öffentliches Recht im internationalen Kontext zu besetzen. Bewerber*innen sollen über fundierte Kenntnisse des österreichischen Staats- und Verwaltungsrechts, eingebettet in europäische und internationale Entwicklungen, verfügen und bereit sein, dieses in Forschung und Lehre umfassend zu vertreten. Besonders erwünscht ist zudem ein Fokus der Forschung auf der öffentlich-rechtlichen Rechtsvergleichung, die auch nicht-europäische Rechtsordnungen einschließt.

Nähere Informationen entnehmen Sie bitte der Ausschreibung. Die Bewerbungsfrist läuft bis 10. Dezember 2025.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This week, we launched our debate “Enabling Access, Fostering Innovation: Towards a Digital Knowledge Agenda in Europe” (ENG): In the EU, existing copyright rules pose significant barriers to research and education. Instead of promoting access to knowledge resources, copyright creates legal uncertainty for researchers and educators and enables information intermediaries to exercise strict control over the use of protected works. This symposium proposes ways out of the copyright conundrum by rethinking copyright as an access right. CHRISTOPHE GEIGER and DAMIAN BOESELAGER open the discussion, highlighting why reforms of the EU copyright law regime are essential. THOMAS MARGONI explores the issue of applying the “old” copyright law to digital content and examines the impact of a landmark CJEU decision. KATHARINA DE LA DURANTAYE shows how the widespread use of digital tools during the pandemic revealed shortcomings in EU copyright law. GIULIA DORE highlights the “Secondary Publication Right” as a key instrument for restoring authors’ autonomy. MARTIN SENFTLEBEN argues that it is time for a general research exemption – a EU-wide rule that reconciles copyright protection with the right to research. JONATHAN RENAUX argues that a fifth Freedom for research and education could make knowledge in the EU more accessible, looking at it through the lens of fundamental rights and internal market law. BERND JUSTIN JÜTTE explores how copyright law in the EU has generated chilling effects on innovation and creativity. Building on this, he and CHRISTOPHE GEIGER argue that the European copyright law regime must be rebalanced to ensure that users’ rights are effectively protected and enforced. Illustrating the stakes for users’ rights, ULA FURGAŁ warns that the press publishers’ right to control content sharing constrains academic discourse.

And if you really have read this far, you must possess a dopamine-disciplined attention span that safeguards your own creativity and innovation. Or perhaps you simply scrolled down. But shortcuts, in the end, are just another form of creative problem-solving.

*

That’s it for this week. Take care and all the best!

Yours,

the Verfassungsblog Team

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an e-mail, you can subscribe here.