“Danger becomes less scary when it is better understood”

Five Questions to Kim L. Scheppele

Last week, we published the results of our Judicial Resilience Project, in which we used scenarios to analyse how authoritarian populists would seek to attack the independent judiciary in Germany. Our study shows that the judiciary in Germany is more vulnerable than often assumed. From numerous international examples and an extensive body of research on “judicial backsliding”, we know that the strategies authoritarian populists employ to pressure, delegitimise, and ultimately capture judicial systems repeat themselves in strikingly similar ways. Few scholars have described these dynamics as profoundly as Kim Lane Scheppele, the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Sociology and International Affairs in the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs and the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University. We talked to her about the state of the US judiciary, determining tipping points, and how to cope with the daily darkness of democratic backsliding.

1. Dear Kim, in the United States, courts have been among the most important and active bulwarks against Trump’s executive aggrandisement. At the same time, they have themselves become the target of massive attacks. Adding to this is the fact that the Supreme Court, as a court that has already been packed and politically skewed, has by and large supported Trump’s agenda. How would you assess the state of judicial independence in the United States at the end of 2025?

We have a decidedly mixed picture of judicial independence in the US. So far, the lower courts are mostly holding the line against autocracy, but the Supreme Court is actively pushing consolidation of power in the executive on all questions that come to it. Trump’s executive orders and lawless actions have generated more than 500 lawsuits (not counting all of the individual immigration cases). In nearly 170 of those cases, lower courts have issued injunctions stopping Trump from doing what he proposed – and those injunctions are still holding. But in the 30 or so cases that have gone all the way to the Supreme Court, that Court has lifted the injunctions and let Trump destroy laws, agencies, careers, and norms while the cases are pending. This has resulted in massive destruction of the US government, which, if the plaintiffs win in the end, cannot be easily rebuilt. Those of us who care about democracy shudder every time a new case gets to the Supreme Court, but some of what the lower courts are doing will hold – and I have been impressed that so many of these judges (including judges appointed by Trump in his first term) have been holding the line even when they are threatened by Trump.

2. The judiciary’s experience also shows that Donald Trump does not proceed subtly or gradually. He is confrontational by “flooding the zone”. Violating the law does not restrain him; on the contrary, he considers himself above the law. Some argue that Trump therefore goes beyond what you described as “autocratic legalism”. It has now been nearly a decade since your seminal article: Has the phenomenon evolved over time?

Trump is and is not quite an autocratic legalist. On the “is” side, Trump has signed more than 200 executive orders creating new law and instructing his minions to enforce it. These executive orders are what the lower courts are enjoining and what the Supreme Court is upholding. If the Supreme Court turns more of these executive orders into formal and final law, we will have a new constitution very soon. Textbook autocratic legalism. On the “not quite” side: Trump has unleashed a reign of terror in American cities under the guise of enforcing immigration laws and preventing crime. But these actions are totally lawless as masked federal officers kidnap people off the streets and disappear them into an inhumane detention system. In addition, Trump has also governed by whim in both domestic and foreign policy. So Trump mixes legalistic and terror-inducing strategies of control. Because Americans are standing up to the reign of terror, however, Trump may be prevented from engaging in legal autocratic capture, which he might otherwise have succeeded in accomplishing.

3. A central feature of judicial backsliding is delegitimising the judiciary as elitist, partisan, or too slow. All too often, these narratives gain traction because they contain a grain of truth. Criticism of the judicialisation of liberal democracies is not new, but it has resonated more strongly in recent years. To what extent are courts themselves, at least in part, contributing to the problem?

Trump has been attempting to delegitimize the judiciary by calling lower court judges activist, rogue, and partisan, and his supporters in Congress have threatened impeachment of judges. But it is the Supreme Court – packed for years by extremist Republicans – that is the activist, partisan, and rogue court. Trump, like most autocrats, claims that the people have put him there (though sometimes he says that God did it). But in the land of 50/50 elections, where polling is ubiquitous, and Trump’s popularity sits in the mid-30-percent favourability range, it’s hard to claim supermajority support. That doesn’t stop him, however.

Attacking the judiciary for being anti-democratic is, of course, an old rogue argument. And if by “democratic” you simply mean that the current occupant of the office is elected, then saying judges are anti-democratic makes sense. But if you think about democracy as the potential to change leaders at the next election, then that shifts the debate over how democracy is defended. If courts try to keep pathways open for democratic rotation if the voters want that, then courts defend – rather than undermine – democracy.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

4. In 2013, you concluded your commentary on “The Rule of Law and the Frankenstate” with a plea for a “forensic legal analysis”: the systematic use of “what-if questions” to expose the vulnerable points of constitutional orders. With our Judicial Resilience Project, we put forward a methodological framework that allows such institutional stress tests to be carried out prospectively and transparently. We found that working with scenarios and combining comparative, doctrinal, and qualitative analysis is particularly effective. This approach allows us to anticipate authoritarian-populist strategies and thus prepare more effectively. What continues to occupy us, however, is how to determine when a system is beginning to tip. What indicators allow us to pinpoint institutional “points of no return” – including in today’s US judiciary?

It’s wonderful that you are thinking holistically because constitutions are meant to work as a system and not as a checklist. So, looking at the relationships among the parts is precisely the way to go. And using scenarios for institutional stress tests is brilliant!

So how does one tell when a system is beginning to tip from democracy into dictatorship? Most of the autocratic takeovers in recent years have occurred when an elected leader attacks the institutions and rules that prevent him from governing by whim. So, the main point of focus should be on the executive and the pattern of actions that this executive undertakes. One or two actions to evade checks on power may be simply enthusiasm; more are signs of danger.

Pay special attention to constitutional “resonant frequency” points – that is, the point where threats are boosted to the point where they destroy the integrity of the thing threatened. The best historical example comes from Germany in 1933, where the parliament was first dissolved and then a state of emergency declared, when the only check on an abusive emergency declaration was the (now dissolved) parliament. The best modern example is the Hungarian constitution, which permits amendment with a single two-thirds vote of the unicameral parliament in a system where the election law makes gaining a two-thirds majority very possible.

5. Many of us find it taxing to engage daily with the ways in which liberal democracies are currently – and may in future be – under threat. How do you cope with this personally? What motivates you to continue researching, explaining, and warning? And how can we protect ourselves and others from the impact that this unrelenting doom and gloom can have on our emotional state and mental health?

I believe that danger becomes less scary when it is better understood – so learning all I can about systems in danger is a way to cope. Staring danger in the face is itself energizing and generates the energy to keep going. Yes, it is exhausting sometimes, but looming dictatorships often generate better political humour, so I really appreciate and collect political cartoons.

But here’s the best part: Times like this also create tremendous solidarity among those who work together to push back against dictatorship. I’ve made so many great friends fighting autocracy in Europe, and now have new friends in the US who are all in for fighting autocracy here. Some of the best people you’ll ever get to know are the ones who take the current threats as a call to action. For example, I’ve been honoured to get to know those of you on the Judicial Resilience Project!

*

Editor’s Pick

by JASPER NEBEL

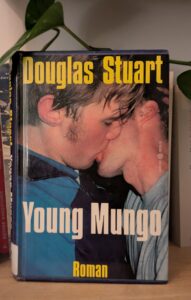

Even the cover is a statement: two men kissing, sweating, living in and for the moment. But the photo – taken in 2002 by Wolfgang Tillmans in a London club – is misleading. While Douglas Stuart’s latest novel Young Mungo does revolve around homosexual love, its setting could hardly be more removed from a gay party. Readers follow 15-year-old Mungo through 1990s Glasgow, an environment sharply at odds with his empathetic nature: his mother is severely alcoholic, and his brother leads a criminal youth gang. This despair manifests physically in Mungo as a tic: whenever he feels uncomfortable, his face twitches. Beyond these everyday hardships, terrible things happen to Mungo – some scenes are tough to take in. Relief comes only when Mungo encounters someone around whom he no longer feels uneasy, someone who makes his face stop twitching. By the end, one can’t help but despair a little over his story. It left me, at least, with a gentle sadness.

*

The Week on Verfassungsblog

summarised by EVA MARIA BREDLER

In Germany, we do not abduct people from the streets like KIM LANE SCHEPPELE reports for the US. But a notion of “we” is readily invoked here too, including in debates on migration. Some call for “us” to “finally speak more honestly” about migration and crime. Who exactly is this “we”? CHRISTIAN WALBURG (GER) reconstructs the discourse and offers reassurance: there are gaps, but the picture of a dominant tendency in the discourse to downplay migration and crime does not reflect reality.

States don’t just construct a discursive “we”; they also create a legal one, separating citizens from others – and those who fall through all the cracks become stateless. After months of devastating violence in Gaza, several Western states recognise Palestine, while Germany continues to resist. SENOL BECIROVSKI (GER) explores what this means under residence law for the stateless Palestinian diaspora in Germany, concluding that recognition would be largely symbolic and would not solve their legal problems – it might even make them worse.

Sweden is also narrowing its own “we”. There, a law is planned that could revoke previously granted permanent residence permits for asylum reasons. REBECCA THORBURN STERN (ENG) explains the context of Swedish migration policy and the serious risks the bill could pose for non-citizens.

EU-wide minimum standards are also under pressure in the migration debate. The European Commission has just launched the first Annual Migration Management Cycle, a concrete step towards implementing the New Pact on Migration and Asylum. The pact promises a better balance between solidarity and responsibility than under Dublin III. But HANNAH PÜTTER und SALVATORE NICOLOSI (ENG) already see early signs that the new system could increase mistrust between Member States, restricting both fundamental rights and access to asylum.

Solidarity is also central to the proposed Reparations Loan, which would use frozen Russian state assets to support Ukraine. The European Council will discuss it in December. Belgium has been the loudest critic, calling it a disguised confiscation. What’s really at stake? PETER VAN ELSUWEGE (ENG) explains the risks.

For a more open form of confiscation, the German government has now put forward a draft law: whether paralysed airports or spied-on infrastructure, drone sightings are increasing – yet it is unclear who is allowed to shoot them down. FINN PREISS and LAURIDS HEMPEL (GER) analyse the draft and explain why no constitutional amendment is needed.

Another controversial draft comes from the Federal Ministry of Justice: the Criminal Code is to be amended to strengthen protection against so-called knock-out drops. HANS KUDLICH and MUSTAFA TEMMUZ OĞLAKCIOĞLU (GER) see no need: existing law already covers these situations and allows for heavy penalties.

There is, however, an undisputedly urgent legislative need at the EU level in another context. For fifteen years, the EU has seemed powerless as Viktor Orbán, the “predator of press freedom,” systematically undermined the media. Most recently, Swiss media group Ringier sold its entire Hungarian portfolio to Indamedia, a government-aligned group that already controls 18 online publications and platforms. KATI CSERES and ANA-CATERINA CIUSA (GER) are now hopeful: the recently adopted European Media Freedom Act could finally protect media freedom and pluralism effectively.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Forschungskoordinator*in

zur Unterstützung des Kollegiums im Bereich des Forschungsmanagements.

(Bewerbungsfrist: 31. Januar 2026)

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

This week, we have also concluded our two symposia.

In her contribution to “The European Convention on Human Rights at 75: Transnational Perspectives and Global Interaction” (ENG), NICOLA WENZEL looks at the right to a healthy environment and warns that superficial comparisons overlook the ECtHR’s rich case law — and risk losing key nuances in translation. JANNIKA JAHN examines how divergent approaches to climate-related obligations unfold across regional systems, UN bodies, and the ICJ, with particular attention to the contours of the European approach. DANA SCHMALZ argues that those attacking the ECtHR for an over-reaching jurisprudence regarding migrants’ rights misconstrue the actual case law. DANIEL THYM outlines four scenarios for the future development of the case law and the possibilities for transformation. ARNFINN BÅRDSEN argues that moving forward, it is necessary to take into account both the inherent features of the technology and the rights that come under pressure by our use of it, mapping out what a potential approach of the ECtHR could look like. MARIA PILAR LLORENS chimes in, warning that when implementing AI tools, Human Rights Courts must ensure that they do not compromise the very rights they are tasked to protect. VERONIKA FIKFAK and LAURENCE R. HELFER add on to this by predicting that more fundamental changes to the process of international human rights adjudication – including at the ECtHR –may ultimately be required. BAŞAK ÇALI celebrates 75 years of the Convention in a personal voice, as a child of this Convention. Closing the symposium, JÖRG POLAKIEWICZ sees us facing two truths as the ECHR turns 75: first, the extraordinary resilience of that promise; and second, the magnitude of the challenges still before us.

We also closed the debate on “Algorithmic Fairness for Asylum Seekers and Refugees”. BEN HAYES looks at the OHCHR’s forthcoming guidance on human rights-based digital border governance and identifies where such guidance can help, and where a significant shift in current State practice is needed. NATALIE WELFENS shows how automation, outsourcing, and fragmented accountability reshape rights protection in migration governance, showing through a case study that existing regulatory frameworks remain insufficient. NIOVI VAVOULA discusses the results of the symposium in a concluding afterword.

So who is this “we” and whom can it hold? Are we also the algorithms we use? KIM LANE SCHEPPELE has reminded us that constitutions work as a system, not as a checklist. What matters is looking at the relationships between the parts. That seems to me a pretty good answer to that question: we should not forget the space in between all our multiple “wes”.

*

That’s it for this week. Take care and all the best!

Yours,

the Verfassungsblog Team

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an e-mail, you can subscribe here.