Brazilian Judges Regulate Elections … and AI

On 27th February, the Brazilian Superior Electoral Court (Tribunal Superior Eleitoral, TSE) issued a set of regulations to govern the 2024 electoral disputes in the country, tackling the use of artificial intelligence (AI) specifically in electoral disputes. Like in many other countries, in 2024, elections will be held in more than five thousand municipalities in Brazil, encompassing more than 150 million citizens casting a vote for city mayors and municipal legislative assemblies. For their comprehensiveness and complexity, these municipal electoral disputes have become essential for the TSE’s experiment with regulatory issues concerning electoral governance, usually testing innovative measures while applying broader electoral and constitutional norms.

Although innovative, these regulations are constrained in their effectiveness and indifference to broader regulatory debates concerning the regulation of AI, showcasing an uncomfortable relationship between judicial and legislative powers regarding digital policy in Brazil that is everything but collaborative (Kavanagh, 2023). Disregarding the complexity of AI, the regulations legitimise the expansion of the judicial branch’s power to deal with digital threats to democracy while not fully engaging with how these threats materialise through the development and use of AI.

The Risks of AI in Electoral Periods

In its most recent Global Risks Report, the World Economic Forum ranked misinformation and disinformation as the global risk in 2024, particularly for their role in disrupting electoral processes and fomenting distrust and polarisation. The use of large-scale and generative AI models diminishes the cost and further amplifies the production of falsified information, allowing synthetic content (e.g., robocalls, deepfakes, AI-powered chatbots) to be easily deployed towards the manipulation of voters and the general public opinion.

Thus, beyond the current paradigm of big data psychographics and algorithmic behavioural manipulation (Howard et al., 2023), AI’s generative capabilities, use of reinforcement learning, and dynamicity create what Fung and Lessig describe as a political campaigning black box in which AI political communication might be severed from its connection with reality by algorithms that prioritise voters changing of their vote instead providing them with accurate information, which might lead to a ‘human collective disempowerment’.

Why is the Brazilian Electoral Courts Regulating the Use of AI?

Avoiding the risks of AI in electoral disputes is thus necessary and cannot be disentangled from the broader discussions regarding the regulation of the technology. In the EU, AI systems deployed to influence voters in political campaigns are classified as “high-risk” and subject to extensive “ex-ante” regulatory scrutiny and possible “ex-post” liability regimes (Kretschmer et al., 2023). As the EU AI Act becomes law before the European Parliament elections in June 2024, member-state electoral management bodies will define how this mandate applies specifically to the oversight of political campaigns before the EU parliament’s new rules governing transparency in electoral campaigns. Meanwhile, the European Commission published draft guidelines on the mitigation of systemic risks for very large online platforms (VLOPs) and very large online search engines (VLOSEs) in the context of articles 34(1)(c) and 35(3) of the DSA (Peukert, 2024).

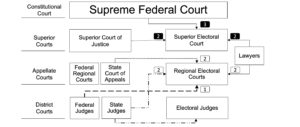

In Brazil, electoral management is done through the judicial system, and a general regulation of AI is still being debated in Congress. The electoral justice framework comprises the Superior Electoral Court (TSE), Regional Electoral Courts (TRE), electoral judges, and electoral boards (Article 118 of the Brazilian Constitution). Although these institutions are prescribed in the Constitution and federal law, they do not have a consolidated composition. Its executive members (Supreme Court Justices, judges, and lawyers) have a mandate of two years and originate from different bodies of the judicial system to oversee electoral disputes (see figure below).

Partial organogram of the Brazilian Judicial System, indicating the origin of executive members of the Electoral Justice branch. (Muniz Da Conceição LH, ‘Electoral Justice and the Supreme Federal Court in Brazilian Democracy’ in Cristina Fasone, Edmondo Mostacci and Graziella Romeo (eds), Judicial Review and Electoral Law in a Global Perspective (1st edn, Bloomsbury Publishing 2024))

Competencies are shared among these courts, which act as administrators and adjudicators of elections for municipal, state and federal offices. The fixed mandate of two years, the heterogeneous institutional background of its members, and the form of selection are mechanisms established to avoid political affiliations and preferences in the administration and adjudication of electoral procedures. Nevertheless, the system is still heavily centralised in the union, and the confluence between the Supreme Federal Court and the TSE raises concerns for the overall functioning of Brazilian democracy (Salgado, 2016).

Because of its amphibious nature as belonging to the judicial branch but performing administrative and regulatory functions, the TSE maintains broad regulatory powers defined in Article 23, IX of the Electoral Code, which provides that the court shall “issue the regulations it deems necessary” for enforcing electoral legislation. This prerogative is exercised towards electoral processes in all of the federation through “judicial resolutions” that, in some circumstances, have an ultra vires effect (Salgado, 2022; Conceição, 2024). A prominent example of this is the TSE’s resolution (23.714/2022), issued expeditiously to combat the spread of disinformation concerning the general elections before the second round of voting in October 2022, expanding the liability of social media platforms and the judicial oversight over big tech companies.

How is the Superior Electoral Court Regulating AI in the 2024 Brazilian Elections?

The TSE issued twelve judicial resolutions regulating and operationalising electoral law norms embedded in the Electoral Code, federal legislation, and the Brazilian Constitution. The resolutions tackle the use of AI in tandem with the institution’s effort to maintain the integrity of the electoral process and curb the effects of disinformation in electoral campaigns, focusing on candidates, campaigns and social media platforms.

AI considerations are most prominent in the regulation of campaigning practices and electoral illicit behaviours. It establishes that the use of AI to create and manipulate electoral campaign content must be explicitly and prominently indicated in its distribution, with clear and visible watermarks highlighting the use of the technology. Non-compliance by the candidate or its campaign management may lead to penalties and sanctions analogous to those prescribed for other electoral crimes, following Article 323, para. 1 of the Brazilian Electoral Code. Furthermore, it expressively prohibits the use and distribution of fabricated or manipulated content supporting false or misleading facts with the potential to cause damage to the fairness and integrity of the electoral process, and the use of generative AI deceptively emulating interactions between candidates and the electorate (AI-powered chatbots), indicating the TSE preoccupation with the potential for AI to amplify societal harms related to disinformation against democratic stability itself.

Most importantly, the TSE new resolution establishes that internet application providers allowing the broadcast of electoral content are liable for adopting measures to prevent or reduce the circulation of illicit content that affects the integrity of the electoral process and must immediately remove illegal content from their hosting services. This liability, therefore, includes but is not limited to (i) the development of effective notification mechanisms, (ii) the promotion of accessibility to channels of report, and (iii) the promotion of corrective and preventive measures. However, It is unclear if these liabilities would also be applicable towards the developers of these AI systems. The resolutions also expressively prohibit using technological tools to modify or fabricate audio, images, videos, or any other media intended to spread the belief of a false fact related to a candidate in the electoral process itself, thus prohibiting the use of deepfakes in electoral campaigns.

More broadly tackling the commercial relationship between political candidates, parties, and social media platforms, the resolution also defines the limits of sponsored promotion (boosting) of electoral campaign content. It prohibits promoting derogatory and harmful content against other candidates and sponsoring the publication of false or misleading information. These provisions consider that using internet platforms and digital messaging applications to distribute disinformation and falsehoods to the detriment of an opponent may configure an abuse of economic power or the improper use of the means of social communication. Additionally, directly tackling the use of social media platforms to broadcast live videos and statements by the political candidates, the resolutions define these live events as official electoral campaigning subjected to restrictions regarding the distribution of electoral propaganda on the internet, such as the sharing and transmission in websites and accounts of legal entities.

Institutional Expansion, Dialogue, or Compromise?

The debate between the judicial and legislative powers concerning the regulation, or lack thereof, of digital platforms vis-à-vis the impact of disinformation in Brazilian democracy has been ongoing since the beginning of former president Jair Bolsonaro’s term (Conceição, 2022a, 2022b). The Supreme Federal Court expanded its prerogative to interpret and apply the Constitution, positioning itself more prominently in the political arena to actively protect the country’s constitutional democracy. This expansion contrasted with prerogatives constitutionally conferred to the Federal and State Prosecutor’s Office and the regulatory deliberations of Congress concerning disinformation and AI (bills no. 2630/2020 and 2.338/2023, respectively), for which the Supreme Court Justice and current president of the TSE, Alexandre de Moraes, delivered a set of proposals based on the experience of the Electoral Court in the past five years.

The effectiveness and legitimacy of these attempts are contested since beyond emergency and institutional failure arguments, both the Supreme Federal Court and TSE’s rationale extensively reinterprets the existing normative framework to define new liability mandates for digital platforms. However, such action has materialised without adequately engaging with these regulatory issues’ broader repercussions and technicalities, particularly the ongoing reports from legal specialists convened in Congress to coherently address them. This institutional blindness impacts the development of solutions that address societal harms, specifically by defining poorly articulated liability rules towards only a few stakeholders, ignoring for example, the role of AI developers in propagating algorithmic biases. It also endangers the overall protection of electoral integrity and enlargement of citizen trust in democratic processes, since it fails to promote cooperation with relevant civil society organisations, fact-checkers, and other actors providing oversight to electoral procedures.

For example, imposing liabilities for platforms to immediately remove content containing disinformation and other forms of hate speech might also lead to the use of AI by those platforms to pre-emptively inhibit these types of speech from being shared. As yet still imperfect technological solutions (Dias Oliva et al., 2021), AI-powered content moderation might lead to false positives, unduly restricting speech in electoral contests, false negatives, allowing negative campaigning and misleading content in a biased manner towards candidates of only one side of the political spectrum (Gorwa et al., 2020), or most probably, both. This is just one instance in which, by jumping the gun on the regulatory debates concerning digital platforms and AI, these judicial resolutions become the normative framework that allows electoral judges and courts to act, expanding their power but not providing effective normative solutions, expanding legal certainty and promoting democratic legitimacy.

Justices in the Supreme Federal Court constantly engage with the media to defend this expansion of power, either indicating that these innovations are still within the remit of their constitutional mandate or reiterating the findings of judicial criminal investigations that uncovered an extensive organisation of digital militias with ties to right-wing politicians and former governmental officials. When the ends purportedly justify the means, one must question if the policy goal has been effectively achieved, which in this particular case requires investigating whether these innovative judicial regulations promote the legitimacy and integrity of the judicial system in tandem with the affordances of the Brazilian institutional design as a whole (Gargarella, 2022). Considering the authoritarian threat and political polarisation still looming in Brazilian and global politics, effectively tackling the impact of AI in these contexts should not be based solely on considerations of immediacy but engage the broader regulatory debate beyond the judicial fora and rely on the expertise and consideration of a more comprehensive set of stakeholders.