Red Card for the Red Card

Dear friends of Verfassungsblog,

Red cards have been all over the place in recent times when it comes to the altercation between the right-wing populist AfD party and the German federal government. For readers unfamiliar with the popular pastime of football/soccer: when a particularly bad foul is committed by a player the referee will dismiss her from the game by showing her a piece of red cardboard. Which is what the AfD aspired to do in October 2015 with respect to Chancellor Merkel and her refugee policy by holding a demonstration under the motto “Red Card for Merkel”, whereupon the Federal Minister of Education Johanna Wanka pulled her respective red card to send the AfD off the field, by reason of the AfD being home to a great many people inclined to shove all numbers of red cards into the faces of Muslims and other minorities. Observers might be forgiven for losing track of who plays foul, who is played foul against, and who is blowing the whistle.

This week, the Federal Constitutional Court tried to disentangle the situation at a public hearing. The AfD had filed a constitutional complaint because Education Minister Wanka had published her “red card” press release on her ministerial website. This is, in fact, a problem under the jurisprudence of the FCC: The state, according to the II. Senate, has to abstain from interfering in the formation of the democratic will of the people which is to be formed bottom-up, “from the people to the state organs, not vice versa from the state organs to the people”. Political parties, on the other hand, do exactly that: According to Art. 21 of the Basic Law it is emphatically their job to “participate in the formation of the political will of the people”. Two years ago the FCC let Minister of Family Affairs Manuela Schwesig get away with a similarly harsh comment regarding the even more extreme right-wing party NPD because Schwesig had spoken as a party politician, not as a state official. Democracy must not turn into a closed feedback loop of political will formation. The Federal Constitutional Court has derived from that insight what might be called a “two-hats” doctrine: government members wear a “state hat” when they speak as state officials and a “people hat” when they speak as party politicians, and they need to make sure that they wear the right hat depending on the capacity in which they speak.

This game of headgear-switching may appear somewhat artificial at times. But the approach of breaking closed feedback loops of political will formation has a lot to commend it. Hungarian democracy would be in better shape if Viktor Orbán were obliged to hold his “Stop Brussels” and refugees referenda from his Fidesz party headquarter. On the other hand: that the right hat on the right head alone is not sufficient to break the feedback loop can be seen in Poland. There, the center of power is the party headquarter anyway, and PiS boss Kaczynski does not need to fiddle with hats for everyone to know who the top dog is and whom better not to cross.

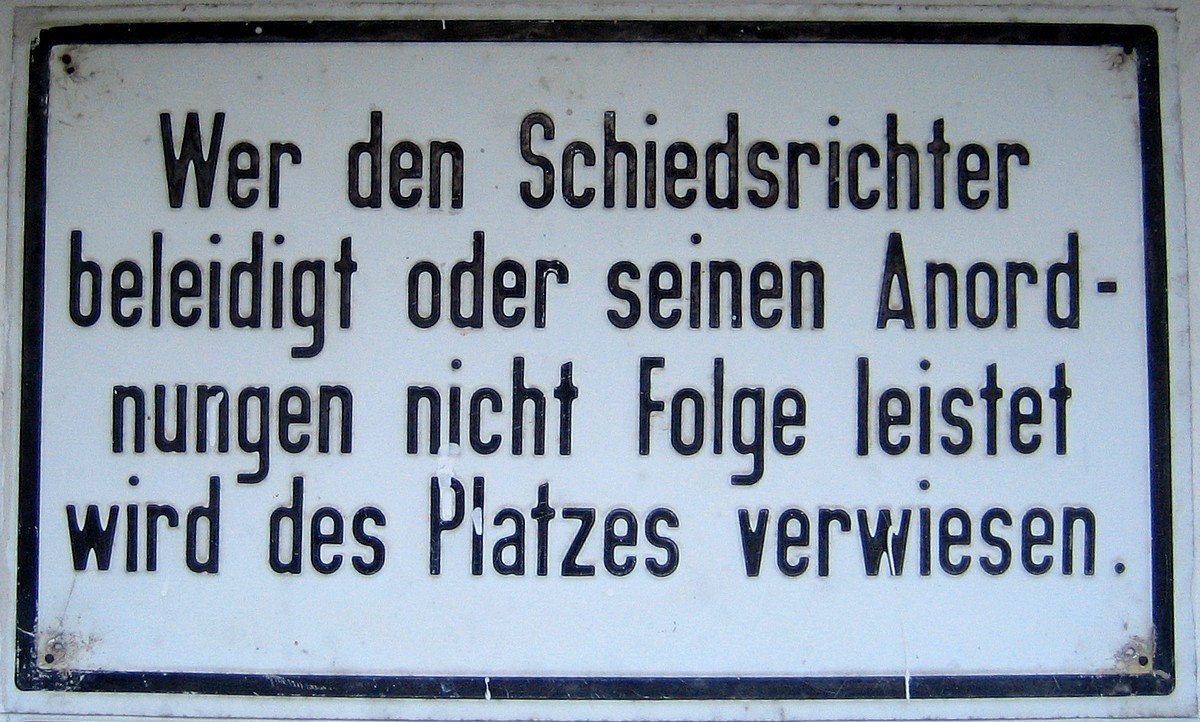

“Those who insult the referee or refuse to follow his orders will be sent off the field.” (c) tin.G, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

To return to the Wanka case: can the Minister defend herself by referring to the German saying that “a coarse log needs a coarse wedge”? Her red card against the red card of the AfD to the chancellor and its general tendency to send off all sorts of players? Exclude from discourse those who exclude from discourse? I do not believe nor hope that the court will accept such an argument. The AfD with all its waving about of red cards and other signals of exclusion should be made object to ridicule, not exclusion, whatever hat one wears at the moment. Pulling red cards instead just confirms that pulling red cards is something a field player is entitled to do. This kind of coarse log needs no coarse wedge, but no wedge at all: a log as coarse as that should not be favoured by the effort to split it.

To trust each other

From Karlsruhe came a rather inconspicuous, yet momentous chamber decision this week, as DANA SCHMALZ reports. In the European asylum system refugees will be deported to where they originally have been granted asylum, in the case of the applicant Greece. German courts just have to check in a general way whether the protection actually exists. In austerity-shaken Greece, however, refugees receive no support at all, so the BVerfG requires the administrative courts to take a closer look.

Reciprocal recognition in Europe is a matter of trust, and trust in the European legal order has been recently made subject of a fundamental essay by Armin von Bogdandy on these pages. JUAN ANTONIO MAYORAL DÍAZ-ASENSIO picks up Bogdandy’s ball and gives it an empirical spin.

The judgment of the European General Court on the “Stop TTIP” initiative is analyzed by SEBASTIAN HESELHAUS with a view to its impact on the European Citizens’ Initiative as a whole: While the Commission’s restrictive attitude towards registering these initiatives has been corrected the Court, the applicants will not benefit all that much in the end as the Court had denied them an interim injunction.

In the previous week, the ECJ had stirred up a lot of dust with its opinion on the Singapore free trade agreement and, according to GESA KÜBEK and DAVID KLEIMANN, done a fairly good job.

Constitutionalism is political compromise, and this is particularly true with the constitution of Afghanistan, written under Western supervision in 2004. ADEEL HUSSAIN shows how in spite – or because – of this constitution Muslim apostates are increasingly threatened by death penalty.

Elsewhere

DANIEL SARMIENTO presents an idea how to purge all the references to the UK from the post-Brexit EU primary law without treaty change: constitutional robotics.

JESSICA GAVRON and JARLATH CLIFFORD analyze the judgment of the Strasbourg Human Rights Tribunal on the complaint of victims of the Beslan attack in 2004 and on the human rights of terrorist hostages in general.

ANDREW COOK reports on the plans of the Tories in the UK to change the electoral law, to repeal the Fixed Term Parliament Act adopted in 2011 and to demand photo ID at the voting booth. ROBERT CRAIG examines how a democratically justifiable substitute for the Fixed-Term Parliament Act should look.

JEAN-FRANÇOIS KERLÉO wonders how President Macron’s intention to make his government appointments dependent of the appointee’s ethical irreproachability fits in with the the French Republic’s system of power.

DARSHAN DATAR draws our attention to a new law in Egypt which empowers the president to bring the independent judiciary under his control.

MING-SUNG KUO and HUI-WEN CHEN reconstruct the ground-breaking verdict of the Constitutional Court of Taiwan on marriage for all as a “3-D dialogue” with its own jurisprudence, with other legal orders and with politics.

News on our own behalf: starting Monday, the fantastic FABIAN STEINHAUER will write a weekly column on Verfassungsblog under the title: “Neues vom Glossator” (news from the Glossator). Those who know him and his wit and erudition will share my elation about this new fixture in the blog’s offer of news and opinion, although, I should add, his highly allusive and double-entendre-rich style exacts a somewhat enhanced command of German. Anyway, reading Steinhauer is always both fun and illuminative, and I am sure you will love it.

All best, and take care,

Max Steinbeis