The Risk of Tunnel Vision in Targeting Russian Disinformation

Disinformation as an essential weapon of war

Contrasting the kinetic warfare that broke out after Russia’s full-fledged invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 with confrontations in the digital space shows that both war arenas came with different implications for NATO and EU member states. While Western powers were able to largely abstain from physical hostilities, limiting their involvement to providing weapons and military material to Ukrainian forces, in the digital sphere such abstention was not possible. Here, confrontations with Russia have not only affected all NATO and EU member states but they preceded the commencement of the recent military escalation. At least since the Maidan protests in Ukraine and the subsequent illegal annexation of Crimea by Russia, Russian intelligence has been flooding Western media spaces with false and deceptive news. The objective of this “firehose” approach to disinformation has been to undermine social cohesion in the West and to fuel distrust of democratic institutions.

Partially coinciding with and partly triggered by the renewed Russian assault on Ukraine, the European Union adopted legislative responses to Russia’s disinformation campaign. On 2 March 2022, it banned two Russian media outlets, Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik, which were perceived as key pillars of Russian propaganda. In parallel and unrelated to the war, it has passed the Digital Services Act (DSA), a landmark piece of legislation that increases pressure on social media platforms to address the problem of disinformation. Nonetheless, Russian disinformation efforts partly appear to have adapted to such containment efforts.

This article aims to illustrate the nature of Russian disinformation, its major themes, tactics, and narratives, and discuss how Russian intelligence has attempted to circumvent the EU’s efforts to contain disinformation as well as how Russian disinformation embodies a persistent threat to the digital health of Europeans. This contribution, however, expresses some caution. Although Russian disinformation remains an active threat, it has frequently been used as a smokescreen. We will demonstrate for the case of the Italian parliamentary elections and the debates surrounding “anti-gender” issues how fears of Russian disinformation have obscured the influence of domestic disinformation actors.

Russian disinformation strategies: fast response and repetitiveness

Russia’s disinformation efforts strongly rely on the persuasive potential of high-volume, diverse channels and sources, along with rapidity and repetition. When diving deeper into how deceptive actors employ these strategies, there are a couple of recurring tactics, themes and geographical aspects that are noteworthy.

Russian disinformation actors employ a variety of tactics to efficiently spread false narratives online. First, they rely on using fake accounts to amplify their narratives. In September 2022, Meta said it has removed networks of such accounts that were based in Russia, explaining that they had reportedly impersonated news websites to criticise European countries for supporting Ukraine since the full-scale invasion. Another common tactic involves the creation of anonymous and impostor websites. Russian government accounts have been linked to registering websites with slightly misspelt names of well-known news outlets containing deceptive information. Lastly, Russia has used influencers and internet trolls to assert its interests and undermine competing narratives by posting manipulative messages on social media, or in the comments section of news articles.

The logic behind these tactics is the attempt to increase the reach of disinformation narratives, as well as to contribute to large quantities of false and deceptive content. Speed and amount are paramount to the Russian strategy. By being always present on multiple channels, it seeks to be more persuasive. Furthermore, endorsements by many people increase people’s trust and confidence in the information, often without any regard for the veracity of the information or the credibility of the individuals who make the endorsements.

Russian propaganda is rapid, and continuous and most important relies on repetition. The pro-Kremlin narratives seem to follow the same pattern: distract from the issue, deny pieces of evidence, demonise the target, shift the blame and repeat. Implementing the element of repetition allows deceptive actors to increase the acceptance of a narrative as true. People tend to believe and endorse narratives that they have encountered multiple times, and even when they are less interested in a topic, people tend to accept, more likely, what seems familiar to them – hence repetition is effective.

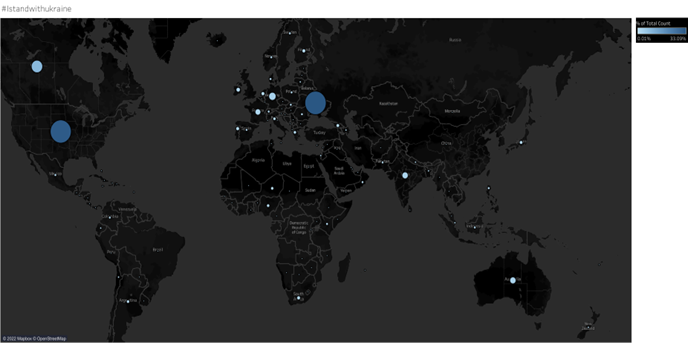

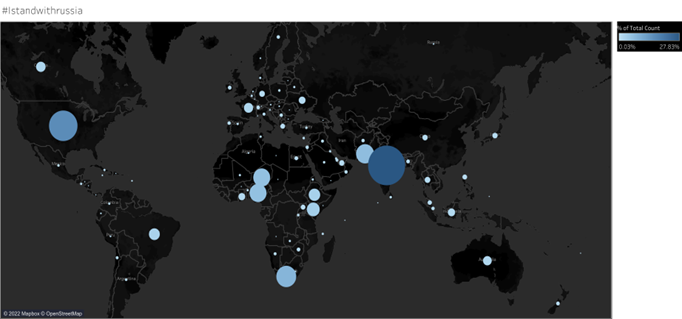

Furthermore, the reach, power and influence of Russian propaganda are particularly potent as Russia spends billions of euros on it. This is especially true outside of the West. One (limited) piece of research by Democracy Reporting International shows that pro-Russian messages have had higher traction in non-Western audiences. The graphs below, for example, illustrate the differences between two sets of hashtags: #IStandwithUkraine and #IStandwithRussia. While the former was far more often reshared among European Twitter users, the latter had a higher prominence in places like Brazil, India, Pakistan, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Graph 1: #IStandwithUkraine

Source: Democracy Reporting International

Graph 2: #IStandwithRussia

Source: Democracy Reporting International

In order not to fall prey to pro-Kremlin narratives the EU took measures to contain Russian disinformation. The most drastic of these was the ban of the two Russian media outlets Russia Today (RT) and Sputnik previously mentioned. Not only was this ban controversial, as some have argued that it was not fully covered by human rights law and could be used as a blueprint by authoritarian leaders (it may be challenged in court), but also the effectiveness of the ban might have to be put in question.

Russian adaptability to containment measures: the limits of bans

Assuming that the bans of Sputnik and Russia Today had no effect would be incorrect. According to research by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) with a focus on France, the ban has resulted in a significant decline in engagement and reach for both outlets on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and Telegram since the ban was implemented. In spite of the fact that they had previously been leading sources for conspiracy theories, false news, and Russian propaganda, resharing of their content had nearly ceased, despite the fact that they were still accessible via a virtual private network (VPN).

However, Russian propaganda has found ways to circumvent the bans to an extent. There are two trends that stand out. On the one hand, stories and messages previously distributed by RT and Sputnik began appearing on websites that existed before the war, but which had not been regarded as mouthpieces for the Kremlin, or on numerous new websites developed since then. As reported by Newsguard, a New York-based monitoring service of online disinformation, by August 2022 there were over 250 pages of this type, many masquerading as think tanks or imitating legitimate news sites. They disseminate false or misleading information about the war in English, French, German, and Italian and portray the Kremlin favourably.

On the other hand, Russian diplomats have taken on a more prominent role in spreading false and misleading information. After the ban on RT and Sputnik, embassies and diplomats started using their – often sizable – following on social media to spread disinformation in a previously unseen manner. Russian diplomatic accounts have aggressively promoted accounts of Ukrainian war crimes and other pro-Kremlin narratives, whether through the promotion of news stories produced by the Russian state media or by disseminating doctored images and videos. As experts have pointed out, it is hard to explain the massive engagement that these messages have received, often with thousands of reshares in a short amount of time, if we do not assume they were part of larger foreign influence campaigns involving bots.

The Focus on Russian Disinformation: A risk of tunnel vision

It is both the sheer volume of Russian disinformation as well as its adaptability to containment efforts that have kept policymakers across the EU on edge. During this year’s elections in Italy and Sweden, there was widespread anticipation of Russian attempts to influence the elections, even culminating in the formation of a new government agency tasked with combating disinformation in Sweden. It is understandable that such fears exist following the, by now undeniable, role of Russia in the 2016 United States presidential election. The risk of placing too much emphasis on Russia, however, should also be considered. It can leave domestic disinformation actors under-explored, and it can also increase Russia´s power as it is perceived to be more dangerous than it is.

It has been demonstrated through research by Politico that Italian politicians and influencers were the main perpetrators of mis-and disinformation before and during the 2022 elections. By no means does this signify that Russia played no role in the creation of false and misleading information. It is even possible that some Italian actors served as Russian proxy agents as messages in support of Russia were prominent among disinformation spread. However, a significant portion of false and deceptive narratives, particularly those aimed against immigrants, seem to have originated from within Italy.

Another example that illustrates this phenomenon is the “anti-gender” mobilisation and building of a disinformation ecosystem around related topics (LGBTQIA+ rights, abortion, and children’s rights, among others) in Europe. When understanding where the funds for actors working in advocacy and on building campaigns online with a false impression of widespread support around these topics is, over 60 percent of funding for anti-gender actors in Europe comes from within Europe. This does not mean that Russia is not an important player in campaigns to mobilise the anti-gender agenda in Europe, in fact, Russia and donors from the US are the two biggest donorrs behind the EU. However, the general feeling of panic about Russian interference in this domain should not overshadow the detrimental role domestic actors have. Disinformation campaigns are an issue to be addressed within the borders of the EU the same way as it is done to foreign actors.

![]()