A Problem of Our Own Making

Understanding Child Labor in the United States

In 2023, Packers Sanitation paid a fine of $1.5 million for employing over 100 children in work environments involving dangerous machinery and chemicals across eight US states. A New York Times investigation also uncovered the prevalence of migrant children working in numerous industries across the US, including Ford, General Motors, J. Crew, Walmart, Ben and Jerry’s, Whole Foods, and Target. Child labor has been identified in small and large companies nationwide, bringing the issue to national and international attention.

The United States is the only UN member state that has not ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The failure to ratify the CRC has had severe (and predictable) implications for children’s rights in the country. A Human Rights Watch report published in September 2022 found that no state has legal protections that scored higher than a “C” on obligations listed in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In measuring child labor, they focus on the agricultural sector, where not a single state has laws that align with the CRC.

The recent spotlight on US child labor has coincided with legislation to reduce child labor regulations. A recent report published by the Economic Policy Institute entitled Child Labor Laws are Under Attack in States Across the Country identified attempts across ten US states to roll back child labor protections in the past two years. Child labor protections are weakening in both Republican and Democratic states. Arkansas (HB 1410) eliminated age verification and parental permission; Iowa (HF 2198) lowered the minimum age of childcare workers (SF 167) and lifted restrictions on hazardous work, lowered the age to serve alcohol, extended work hours, and strengthened protection of employers from civil liabilities if children are hurt. Attempts to introduce a sub-minimum wage (such as Nebraska’s LB 15 bill) that would pay children less than adults for the same labor are another example. At the federal level, a bipartisan bill was introduced to Congress in March of 2023 that would allow children to participate in logging under the Future Logging Careers Act despite logging being a hazardous form of employment.

Why has there been an increase in child labor across the US? In many ways, this is the wrong question. Child labor has been a persistent problem in the US for decades. Scholars have pointed out that child labor was significant and increasing at the end of the 20th century (see here and here). Reporting child labor violations in the 21st century is also not new (see here, here, and here). The better question is why this is only just now receiving national and international attention when it hasn’t before. We argue that this results from stagnant wages, growing inequality, and a labor awakening accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is child labor?

The conversation on child labor concerns the worst forms of child labor that harm a child’s education and mental or physical well-being. Most children around the world engage in child labor. Being paid to do chores around the house is child labor, as is k-12 education, which is mandatory in most countries and unpaid. We need a definition of what counts as child labor and what does not. Here we use the criteria we apply in the CIRIGHTS data project, which codes government respect for human rights worldwide. These rules incorporate International Labour Organization conventions (182, 138, 124, 78, 77) and recommendations (190, 146, 125, 79) about child labor.

The CIRIGHTS data project defines child labor as:

- Children younger than 14 working in any job

- Children younger than 18 working aboard ships

- Children younger than 18 working in a dangerous occupation

- Children under 18 working at night (except for vocational training or apprenticeships)

- Children working without a clean bill of health

- Children employed during regular school hours

- Children who are sexually exploited, children serving in armed conflict, slavery, trafficking, debt bondage, and participating in illicit activities

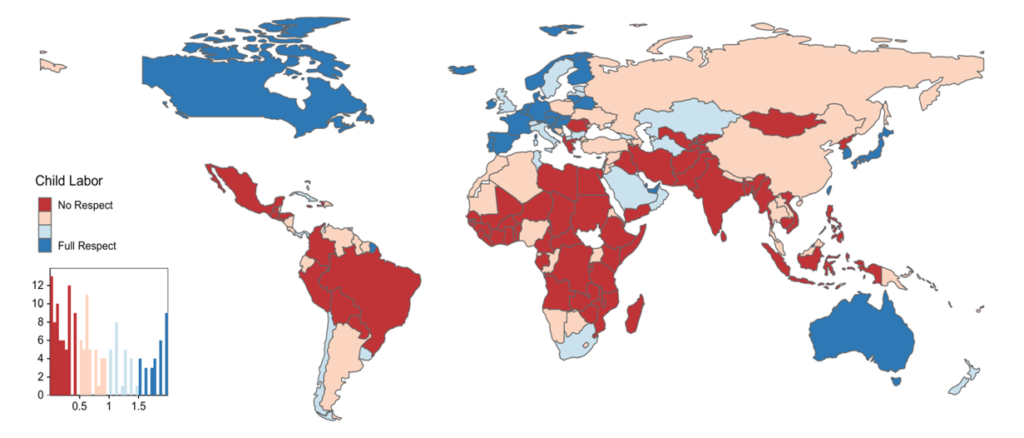

Using this criterion, we score all countries (besides the US) for child labor between 1994 and 2021. We find that child labor has been getting worse and is one of the least respected human rights around the globe. The figure below is taken from our 2022 CIRIGHTS report. It shows the average respect for child labor in the 21st century. A score of two represents full respect and is indicated by a dark blue; a score of zero indicates widespread violations and is characterized by a dark red.

The United States scores below the median if we apply these same criteria to the United States. The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act outlawed child labor, with many exceptions for the agricultural sector. As a result, child labor has always been a problem in agriculture. Child workers (alongside adult workers) have few worker rights protections in this sector. The ubiquitous child labor in the formal and informal sectors (as discussed in the New York Times piece) would put the US at the bottom of the developed world and on par with many autocratic nations in its legal protections and its protections in practice.

Causes of Child Labor

A simplified explanation by Swinnerton and Rogers (1999) identifies three sources of child labor: the cost of child workers is less than the cost of adult workers, families send their children into the workforce when they do not have enough income to support the family, and growing inequality which allows child labor to occur in developed countries.

Children can be employed cheaper than adults and are less likely to unionize than adults. This makes it more profitable to employ child workers compared to adult workers. As the national movement for a $15 minimum wage began seeing victories, and union drives in companies like Amazon have been successful, labor costs have increased. Employers could solve worker shortages by paying workers a higher wage, improving working conditions, and creating attractive jobs. An alternative is to make it easier to hire children, which suppresses the strength of labor movements, reduces wages, and is the current strategy of many US businesses.

Demand for child labor comes from business groups like the National Restaurant Association, which helped spearhead Iowa’s SF 167 bill. There is also a demand from conservative think tanks like the Foundation for Government Accountability, which has drafted or revised much of the legislation introduced in the past two years. Both lobbying efforts frame child labor as a parental rights issue. Child labor regulations then are seen as an overreach of the government. This argument is the same one that killed efforts to ratify the CRC. Much of this legislation is not aimed at outright saying child labor should be legal but rather removing the mechanisms for identifying and enforcing child labor regulations. For example, in Arkansas, after a public backlash against the Youth Hiring Act (HB 1410) of 2023, they passed SB390 in April 2023, increasing penalties and fines and adding criminal penalties. This strategy of reducing the ability to monitor and enforce child labor protections while marginally increasing penalties will likely be the strategy from now on.

The supply of child labor is largely driven by poverty. Families that would otherwise send their children to school are forced to choose between affording rent, medical treatment and bills, and other necessities and keeping their child out of the labor force. In the US, roughly 2/3rds of bankruptcy fillings are tied to medical bills. The US is the only industrialized country without a universal healthcare system, which has pushed many families into poverty. Since most employees’ healthcare is tied to their job, being fired (including for health reasons) often leaves families unable to pay for medicine or medical expenses. This is one of the many economic strains on families that push children into the workforce. A weak social safety net, stagnant wages, growing inequality, and continual public education funding decline have all contributed to a growing child labor supply.

The US immigration system is another source of child labor. Undocumented workers are at risk of being deported and are economically vulnerable. If migrant children lose their job, they are much less likely to complain about labor violations than US adult workers. US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) also ramped up its repression under the Trump administration. Migrants became even less able to take advantage of institutional protections than in the past. It is common knowledge that the food service industry in the US has a large undocumented population. If adult workers are unable or unwilling to work for low wages, then migrant children can be substituted. The historical inability of migrants to complain about labor rights violations and growing child migration has left migrant children at risk of deportation and poverty.

Solutions to Child Labor Problems?

When the Convention on the Rights of the Child was created, the United States participated under former presidents Ronal Reagan and George H.W. Bush but ultimately failed to ratify the Convention. The argument for why the US did not ratify the treaty mirrors those the Foundation for Government Accountability has used (see above). When thinking about child labor, it is unsurprising that we are lagging behind the rest of the world. The US has only ratified 14 of the 189 International Labour Organization conventions, has not ratified the International Convention on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, and has generally not incorporated economic rights into its domestic legal framework.

The current approach to addressing child labor at the federal level revolves around increasing the penalties for firms. Current penalties are insufficient to deter firms from hiring children. The Packers Sanitation fine of $1.5 million is about $15,000 per child found working. Given the firm’s size, this fine is insufficient to deter future violations, let alone signal to other firms that child labor is too risky. A bipartisan House bill introduced in March 2023 aims to raise penalties to ten times their current level. A bill introduced in April 2023 aimed to increase the penalties to $700,000 per violation and include up to 10 years of jail time for repeat offenders. Much of the federal effort to reduce child labor has been aimed at increasing the cost to businesses of hiring children. However, efforts to ban child labor or simply deal with business demands can make things worse. Simply raising fines is unlikely to reduce child labor. About 1,000 federal labor inspectors are responsible for monitoring all businesses across the country, making finding and enforcing these penalties unlikely in states that have rolled back child labor protections.

A comprehensive approach is needed to address both the supply, demand, and inequality that makes child labor possible. Any solution will be more complicated and require more discussion than is possible here. Choosing between what is politically feasible versus what is necessary to address the real causes of child labor is always an issue in politics. However, scholarly research has pointed to some policies which are effective such as improving worker rights and strengthening labor unions, improving the healthcare system, investing in education, strengthening the social safety net, liberalizing the immigration system, ratifying international human rights instruments related to economic rights, and addressing other children’s rights in the country such as child marriage, corporal punishment, and juvenile justice issues.