Lucretia Mott (née Coffin)

Uncompromising Non-Resistance

For abolitionists, she cared too much about “the woman question”, for feminists, she was too concerned with anti-slavery reforms. Lucretia Mott was caught in a crossfire of human rights movements. Her relentless activism for universal liberty and freedom allowed her to embrace both efforts.

“(The abolitionist) will not love the slave less, in loving universal humanity more.”

Female anti-slavery and free produce movements

On 3rd January 1793, Lucretia Coffin was born in Massachusetts. The Quakers (Society of Friends) informed her upbringing on the island Nantucket where she spent the first 10 years of her life until the Coffin family moved to Boston. Like her siblings, Lucretia attended a public Quaker school where children were taught about the horrors of slavery.1) The Quakers were important abolitionists. While slavery remained legal in Massachusetts until 1783, the Nantucket Monthly Meeting had already repudiated slavery in 1716. The education in Quaker tenets, e.g. the immorality of slave labor, continued at the Nine Partners Boarding School that Lucretia attended from age 13 onwards. There, she met James Mott, whom she married in 1811. The couple moved to Philadelphia, a city that due to the growing community of free Blacks was becoming a “hotbed of abolitionism” by the 1830s.

The profound suffering of slaves moved Lucretia to take action. She was one of the few women attending an anti-slavery convention in Philadelphia in 1833 which formed the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). As a woman, she was not entitled to become a delegate or signatory to the convention’s Declaration of Sentiments.2)

Only days after the convention, Lucretia and other female abolitionists founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). The Society mirrored Mott’s convictions. They advocated for immediate emancipation and opposed political action. This was in line with William Lloyd Garrison’s teachings of “no-governmentism”, rejecting any participation in a political system burdened with slavery. The interracial constitutional committee emphasized the PFASS’s commitment to racial equality. The existence of an interracial organization in and of itself challenged the fear of miscegenation in a predominantly racist America.3)

In 1837, female abolitionists gathered to hold the first national Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women. A second convention held a year later was attacked by a violent mob hurling bricks at Pennsylvania Hall while the convention took place inside. Thousands of aggravated individuals spread throughout Philadelphia, attacking other symbols of racial integration.4) The events did not intimidate Lucretia and the PFASS into abandoning their efforts; in 1839 they held a third Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women.

The attack, however, impacted African American women who expressed their concerns about becoming the mob’s next target. The PFASS urged them to attend despite the “risk to their physical bodies or their social respectability”, ignorant of the fact that unlike white women, African American women could not count on protection based on their gender.5)

In 1840, Lucretia and James travelled to London for the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention as a delegate of the AASS, the PFASS, and the American Free Produce Association. She followed the debates closely, in particular those on free produce. The abstinence from slave-grown products was one of Lucretia’s strongest convictions. By choosing abstinence, every individual could liberate themselves from the “grasp of slavery”.6) Elizabeth Coltman Heyrick’s pamphlet from 1837 spoke to Mott and she agreed that “when there is no longer a market for the productions of slave labor, then, and not till then, will the slaves be emancipated.”7) Few abolitionists supported the Free Produce Movement, many deemed it ineffective. Abolitionists were also split on the practice of buying slaves’ freedom. Lucretia felt strongly that this aided the institution of slavery and constituted an implicit concession of the slaveholders’ misconception that human beings are property.8)

Another dividing factor was whether abolitionists should resort to violent resistance. The dissent became particularly apparent when the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was passed, regulating that escaped slaves had to be returned to their master upon capture. While united in their opposition to the law, the proposed means of resistance differed immensely among abolitionists. Garrisonians like Mott and the PFASS rejected any use of “carnal weapons for the deliverance from bondage” and reiterated their commitment to non-resistance. They favoured petitions and fundraising. The increasingly violent clashes between pro- and anti-slavery forces leading up to the Civil War challenged their hardline stance. Even though they concurred with the motives, they distanced themselves from their methods.9)

With the ratification of the 13th Amendment, many abolitionists believed their work to be done and joined freedmen aid associations instead which focused on providing education for freed slaves. Lucretia and the PFASS vowed to continue their efforts until true emancipation was reached. Lucretia also joined the Friends Association for the Aid and Elevation of the Freedmen (FAAEF) but distinguished between the goals of the anti-slavery and freedmen’s aid movements.10)

CC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; “Lucretia Coffin Mott” by Joseph Kyle

Women’s rights advocacy

Racial equality and the abolition of slavery always remained at the heart of Lucretia’s activism. Nevertheless, she often included women’s rights in her sermons and speeches.

Before female abolitionists like Mott started challenging the notion that women belonged in the “private sphere”, it was largely uncommon for women to speak publicly.11) Lucretia blamed oppressive customs and the misconstrued interpretation and application of Scripture for confining women to this private sphere.12) She asked women to demand “that every civil and ecclesiastical obstacle be removed out of the way”.13)

Mott recognized the inseparability of racial and gender equality. As an elected delegate to the first women’s rights convention in 1848, she urged consideration of how women’s rights interconnect with other causes, namely slavery.14) This not only reflected her egalitarianism but also an early understanding of intersectionality.

Early influences such as coeducational schooling and Nantucket women taking over the family business due to their husbands’ absence during the whaling season instilled a sense of equality in her regardless of gender.

Lucretia’s lived experiences with discrimination fueled her dedication to the women’s rights movement. As an assistant teacher at Nine Partners, she noticed how the female head teacher earned less than young male teachers.15) As an elected delegate to multiple conventions, Lucretia repeatedly experienced discrimination and exclusion. At the Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840, female delegates were refused admission and confined to the gallery, even after some male abolitionist offered their support.

Universal suffrage

After the Civil War, the PFASS shifted their focus to fighting segregation on Philadelphia’s railway lines and to securing African American men the right to vote. The fact that, like the PFASS, many abolitionists excluded (white and black) women’s suffrage from their calls for “universal suffrage” frustrated women’s rights advocates. Lucretia backed both movements, although her support of women’s suffrage was fortified over the course of her life.

In the beginning, Lucretia had not supported calls for women’s suffrage, even trying to discourage Elizabeth Cady Stanton at Seneca Falls. Her lack of support was not founded in disdain for women’s elective franchise but for political participation. Later, albeit reluctantly, she joined women’s suffrage demands. “Far be it from me to encourage women to vote, or to take an active part in politics, in the present state of our government. Her right to the elective franchise, however, is the same, and should be yielded to her, whether she exercises that right or not.” Eventually she asserted the importance of women’s participation in the political sphere for obtaining peace.16)

Lucretia looked past her initial doubts about uniting both suffrage movements when she became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association which advocated for “universal suffrage” irrespective of race or gender.

Hicksite Quaker

At a meeting of the Society of Friends in 1821, Lucretia was moved to speak and afterwards recognized as a minister. Quakers have recognized female ministers since the 17th century.

Mott remained a minister until the schism of 1827 which spawned two branches of Quakers: Orthodox and Hicksites. The schism was triggered by dissent on two main issues.

The first was the shift away from “the inner light” – the Quaker principle that all people are capable of directly experiencing the divine nature of the universe – to scripture for invoking “authority” following the influence of evangelicalism. Lucretia was among many Quakers who were dissatisfied with the new direction and followed Elias Hicks who believed the inner light to be primary to the Bible. Mott condemned man-made rules presented as divine truth and implored “individual authority in matters of religion”.17)

The second topic dividing Quakers was slavery; Hicks criticized the elders for violating the “antislavery testimony”.18)

Pacifism and moral suasion

After the Civil War, Lucretia began actively participating in the Peace movement by co-founding the Universal Peace Union. Lucretia’s condemnation of war and violence reflected the Quaker Peace Testimony. She detested anything that incited violence such as war toys for children, military schools, or capital punishment.19)

Lucretia was uncompromising in her non-resistance. She chose principle over pragmatism. To her, any deviation – even for the right reasons – was unjustifiable.20)

It explains her long-lasting commitment to the Free Produce movement and why she has never budged from her stance on slave liberation through purchase or force. Her lack of pragmatism attracted criticism. She was accused of valuing her purity over the welfare of individual slaves.21)

Her radical pacifism should, however, not be misunderstood as an avoidance of confrontation. While she rejected every notion of physical altercation, Mott sought verbal confrontation. She believed in moral suasion as a powerful tool for instigating change and felt obliged to engage slaveholders in conversations about the immorality of slavery. This active form of moral suasion could be interpreted as “aggressive”.22) Robert Purvis therefore described her as “the most belligerent Non-Resistant”, a characterization Lucretia enjoyed.23)

Freethought and dogma resistance

At a first glance, Lucretia seemed to inhabit many opposing beliefs: a woman of strong faith who continuously challenged religious customs and institutions, an egalitarian who was reluctant to advocate for women’s suffrage and an abolitionist who opposed the liberation of slaves through force or purchase. At a second glance, however, this was the consequential result of her resistance to dogmas. Rather than adhering to other’s fixed conceptions, Lucretia adhered to the rules of reason. This allowed her to unite the support of social movements with her unwavering principles. She believed liberation from dogmatic authority would be achieved through independent and free thinking.24) Lucretia Mott considered this anti-dogmatic approach to be part of a holistic reform.

The only compromise Lucretia made was that of remaining in the Society of Friends despite her fundamental disagreement with Quaker leadership on Scripture, slavery and the role of women. Many abolitionists withdrew from denominations that failed to condemn slavery.25) Lucretia stayed a Friend intending to reform the Society from within. Doubts about the genuineness of her convictions were unfounded; she continued to attack ecclesiastical power, i.a. the doctrine of atonement.26)

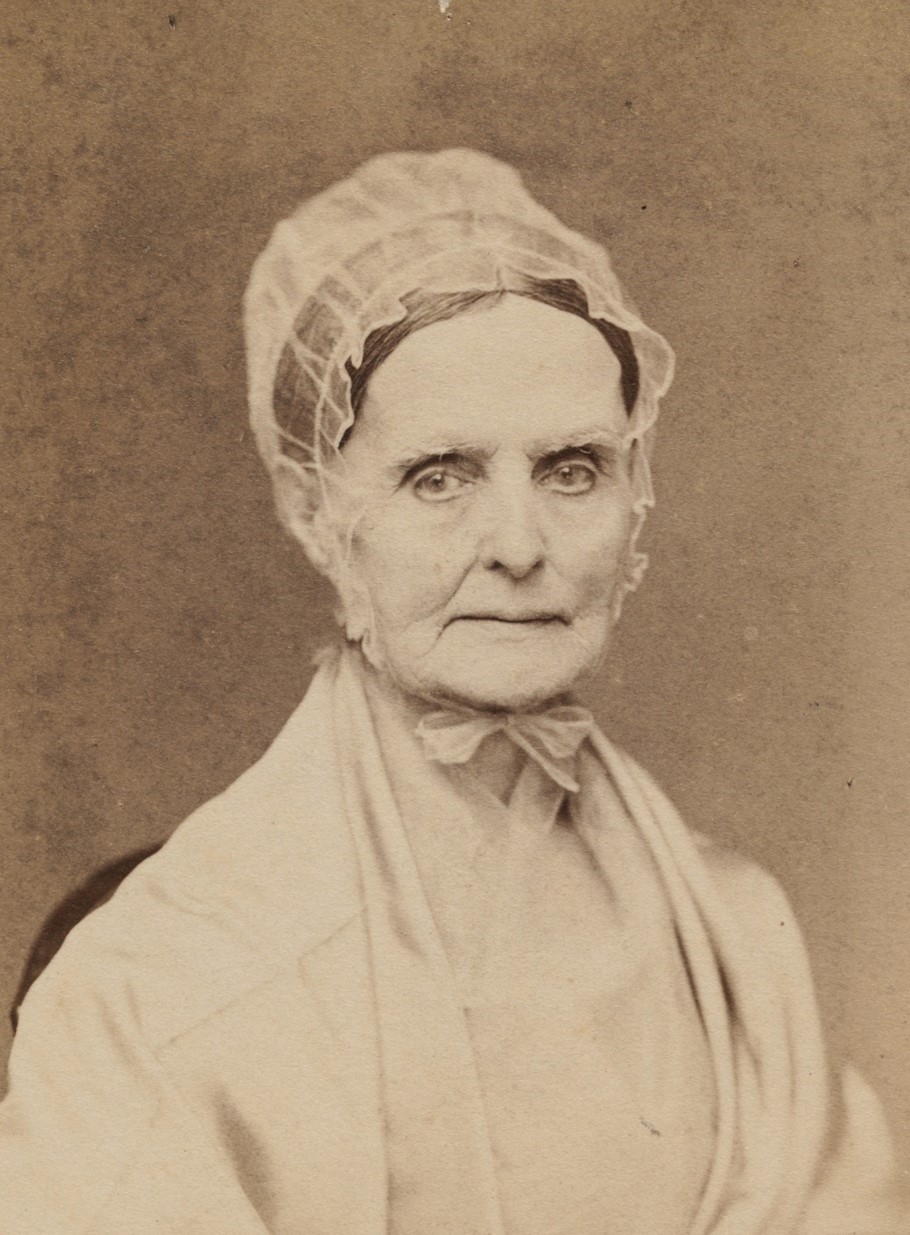

CC: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, “Lucretia Coffin Mott” by Frederick Gutekunst

Lucretia Mott relentlessly dedicated her life to advocacy. The mother of six was an eloquent and impactful speaker who enchanted and appalled audiences equally. While her ideas are widely accepted and praised today, they were the reason for agitation, incomprehension and paternalism among her contemporaries. This could not deter her from fighting for what she believed in.

Further Reading

- Cromwell, Otelia, “Lucretia Mott”. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1958.

- Bacon, Margaret Hope, “Lucretia Mott: Pioneer for Peace.”, Quaker History 82, no. 2, 1993.

- Stanton, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Gage, Matilda Joslyn and Harper, Ida Husted, “The history of woman suffrage.”.

- Vetter, Lisa Pace, “Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott: radical ‘co-adjutors’ in the American women’s rights movement.” British Journal for the History of Philosophy 29, 2021

- Hare, Lloyd C. M., “The Greatest American Woman Lucretia Mott”, 1937.

References

| ↑1 | Carol Faulkner, Lucretia Mott’s Heresy: Abolition and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011, p. 5. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 64. |

| ↑3 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 67. |

| ↑4 | Harriet Hyman Alonso, “Peace as a Women’s Issue: A History of the U.S. Movement for World Peace and Women’s Rights”, 1993, p. 34. |

| ↑5 | Carol Faulkner (2011), pp. 79, 80. |

| ↑6 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 99. |

| ↑7 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 54. |

| ↑8 | Carol Faulkner (2011), pp. 114, 115. |

| ↑9 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 172. |

| ↑10 | Carol Faulkner (2011), pp. 182,183. |

| ↑11 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 65. |

| ↑12 | Carol Faulkner (2011), pp. 72, 155. |

| ↑13 | LCM to the Salem, Ohio, Woman’s Convention (As cited in Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 147). |

| ↑14 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 141. |

| ↑15 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 34. |

| ↑16 | Harriet Hyman Alonso (1993), p. 44. |

| ↑17 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 60. |

| ↑18 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 5. |

| ↑19 | Harriet Hyman Alonso (1993), p. 43. |

| ↑20 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 116. |

| ↑21 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 177. |

| ↑22 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 163. |

| ↑23 | Lisa Pace Vetter, “The Most Belligerent Non-Resistant”: Lucretia Mott on Women’s Rights’, The Political Thought of America’s Founding Feminists, New York University Press, 2017, p. 145. |

| ↑24 | Lisa Pace Vetter (2017), p. 156. |

| ↑25 | Carol Faulkner (2011), p. 109. |

| ↑26 | Carol Faulkner (2011), pp. 120, 121. |