No Kidding!

Mapping Youth-Led Climate Change Litigation across the North-South Divide

When Greta Thunberg invited us adults to panic, few of us thought that she was about to sue, if only because litigation is quintessentially a game for grown-ups. On 23 September 2019, the day of the UN Climate Action Summit, Ms Thunberg and 15 other minors from 12 states and five continents filed a complaint before the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) to protect their individual rights to life, health and culture, which the plaintiffs described as already compromised by the effects of climate change, crucially as a result of governments’ culpable inaction.

Since only about a quarter of UN Members ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on a communications procedure, the choice of defendants was limited and finally fell on Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany and Turkey. Sacchi et al. v Argentina et al. offers a remarkable example of a demand for justice crisscrossing the North-South divide. And it is the closest thing we ever had to a worldwide trial against adults. Although the case eventually foundered on the lack of exhaustion of domestic remedies, the CRC, in declaring the case inadmissible and yet within its jurisdiction, has offered valuable pointers for a litigation campaign that young people are now pursuing worldwide. Our contribution provides an overview of the relevant cases, many of which still pending, and tries to pinpoint the drivers and possible trajectories of a global phenomenon which could go some way towards redressing the injustice the Global South is suffering as a result of global warming.

Scope of Investigation

Relying mainly on the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law’s databases, we inventoried all cases – whether civil, administrative, constitutional or international – in which the plaintiffs are young people complaining that public authorities are not doing enough to combat climate change. Instead of sticking to a definite age threshold, we included all lawsuits a salient feature of which is the applicant’s young age. Based on this criterion, we left out mass cases such as VZW Klimaatzaak v Belgium and Notre Affaire à Tous et al. v France, which, although counting youths among a huge number of applicants, do not advance arguments relating to youth’s vulnerabilities and rights beyond general references to the interest of future generations.

We employed a broad notion of adjudication, such that our survey even includes Environmental Justice Australia v Australia, which stems from a complaint that four people aged between 14 and 24 recently submitted to three UN Special Rapporteurs (such complaints are based on law and require the petitioning authority to make a determination as to their merits before deciding whether to send a warning to the respondent state).

Finally, we have included cases where climate change, though not the main subject of the complaint, is still an important aspect of it. For example, the case Six Children of Cité Soleil and SKALA Community Center v Haiti, which is pending before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, chiefly concerns waste disposal but, as the applicants contend, “climate change magnifies the adverse environmental conditions facing children”, calling for additional adaptation measures (see here, at 32).

Beyond Lovejoy’s Law

Skeptics might think that youth-led climate litigation is but an elaborate expression of Lovejoy’s Law, a presumptive law of social psychology named after Helen Lovejoy, the Reverend’s wife in The Simpsons, to whom we owe the iconic outburst: “Won’t somebody please think of the children!”. According to Lovejoy’s Law, the love for children is likely to be invoked as an emotional tiebreaker when opponents in a political dispute run out of rational arguments. Adults concerned about global warming may thus wish to recruit children to advance a cause by anti-majoritarian means, given the enduring failure of representative democracy and diplomacy.

Litigation involving children as plaintiffs is likely to have a strong media impact. And saying no to a child is even harder before an audience ready to lash out at the insensitivity of fellow adults in robes. The lawyer of Rabab Ali, a now twelve-year-old girl whose climate case has been pending before the Supreme Court of Pakistan since 2016, used language in keeping with Lovejoy’s Law: “this Hon’ble apex Court must consider the small voice of youth Petitioner and the children of Pakistan as if they were their own children” (see here, at 14).

While it is too early to say whether Lovejoy’s law is producing any effect in this field (rulings like that of the National Green Tribunal in Ridhima Pandey v India suggest not), it is undeniable that youth-led litigation has gone mainstream by now. An NGO working on climate litigation and prioritising cases “not already receiving adequate support from other NGOs and founders” avoids involvement in “children’s climate cases” precisely for that reason (correspondence on file with authors). It is rather the youth who do not believe in Lovejoy’s Law. As Ms Thunberg famously told us from the podium of COP24 in Katowice, “you have ignored us in the past and you will ignore us again”. Instead of addressing adults as wise and caring parents – the ideal agents of Lovejoy’s Law – Ms Thunberg’s speech infantilised them: “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is; even that burden you leave to us, the children”.

A similar attitude prevails within World’s Youth for Climate Justice (WYCJ), a transnational coalition of young adults with its cradle in the Pacific Islands and involving activists from the Philippines, the Caribbean, Brazil, South Africa, and Europe. WYCJ lobbies governments to get the UN General Assembly to ask the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for an advisory opinion on what would be “the obligations of states under international law to protect the rights of present and future generations against the adverse effects of climate change” (see here, at 29). In their painstaking effort to formulate a question at once effective and capable of attracting sufficient consensus within the Assembly, people at WYCJ “value [the] wisdom” of “older generations”, with the caveat that “[i]n the end, youth make the decisions”.

Alliances with adults are necessary because climate change litigation is an expensive and knowledge-intensive business. Behind the abundant and generally pro bono supply of top-notch legal services lies an intricate web of funders, including public agencies, individual donors, and financial operators such as the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (whose director has been referred to by Bloomberg as the Greta Thunberg of the hedge fund industry). However, tactical alliance with adults, although profitable, is not nearly as important for young people as joining forces with their peers worldwide.

World Youth’s Apocalyptic Turn

Transfixed by Al Gore’s The Inconvenient Truth, Alec Loorz from Ventura, California, founded Kids vs Global Warming at the age of 12 and later led the first wave of youth-led climate change litigation in the early 2010s. Mr Loorz had a clear idea of the need to forge a global youth alliance to address an existential threat that adults felt too little about. To this end, he created iMatter, a smartphone app with which young people all over the world (i.e. the few who in those days had access to the necessary technology) could network, exchange and store information, and organise campaigns and rallies. One decade later, during the pre-COP26 youth event held in Milan on 28-30 September 2021, Greta Thunberg pointed out that “the climate crisis is […] the symptom of a much larger crisis”, “a crisis of inequality that dates back to colonialism and beyond”. WYCJ, the youth organisation that tries to put climate change on the ICJ’s table, refers to itself as “a decolonial and anti-oppressive space”.

Youth solidarity across the North-South divide has been intensifying lately and spawned a vast grassroots movement arguably because prospects of continuous growth, within which trajectories between rich and poor could keep on diverging as long as the rich funded the “fight against poverty”, have faded. It was Greta Thunberg who decisively voiced the feeling that catastrophe looms large and concerns everyone, regardless of residence or income. As an Australian 18-year-old girl involved in a climate case told The Guardian, “I have struggled with depression and anxiety brought on by the knowledge that without action by our governments, the planet I live on has an expiry date”.

Global youth solidarity is part of the movement’s founding myth. The 2018 docu-manifesto Youth Unstoppable: The Rise of the Global Youth Climate Movement opens with the then 13-years-old spokesperson for a Canadian youth-led NGO addressing a half-empty hall at the 1992 Rio Conference: “I am here to speak on behalf of starving children around the world whose cries go unheard”, said Ms Cullis-Suzuki. That speech, which by the way made no mention of climate change, reflected a compassionate attitude of the North towards the South and brimmed with Lovejoyan undertones. Ever more distrustful of adults’ feelings, today’s youth have turned apocalyptic and embraced litigation as a tool of rebellion.

The Radicality of Youth-Led Litigation

Regardless of the procedural avenue selected by the plaintiffs, virtually all the cases concern an alleged violation of fundamental rights, drawn from either domestic constitutional law or international human rights law, or both. In cases such as Urgenda Foundation v Netherlands, A Sud et al. v Italy, and Maya Ozbayoglu v Poland, human rights discourse colours claims formally made under the law of torts. Instead of claiming compensation for a damage deemed too great to remedy, the plaintiffs typically ask that the state put an end to its illegal conduct, first and foremost by adopting emission targets compatible with the objective of limiting temperature increases to 1.5 or 2°C by 2100, relative to pre-industrial levels.

In Environnement Jeunesse v Procureur général du Canada, plaintiffs are asking for symbolic compensation of $100 for each member of the class action, that is, all Québec residents under the age of 36. As the resulting sum would be too large, they propose to exchange compensation for the adoption of wide-ranging mitigation measures. In the cases examined, the plaintiffs invariably ask the court to recognise an injury that has already occurred and is ongoing. However, remedies sought are prospective only. By highlighting the reality of the harm, the plaintiffs aim at convincing the court that they have an arguable case as well as signal that turning to action is urgent.

It is important to stress that the line of cases we deal with is not merely a spinoff of the climate change litigation’s human rights turn boosted by the Paris Agreement’s bottom-up approach to emissions reduction. The rise of youth-led litigation accompanies such turn and operates as its radical edge, in three ways.

Firstly, children’s greater vulnerability to the adverse effects of climate change makes it easier to have their status as victims recognised.

Secondly, the younger the applicant the longer she or he will endure such effects, which, incidentally, will grow more severe over time. This circumstance gives rise to a claim for equal treatment, which is becoming a distinguishing mark of youth-led litigation. The CRC recognised the merits of this claim by stating that children “are particularly affected by climate change, both in terms of the manner in which they experience its effects and the potential of climate change to affect them throughout their lifetimes, particularly if immediate action is not taken” (see here, at para. 10.13).

Thirdly, and most importantly, the vast majority of youth lives in developing and least-developed countries – 85 percent according to UN sources – often in areas particularly exposed to the adverse effects of climate change. There is therefore strong intersectionality between young age, poverty, and climate victimhood. As Kenyan climate activist Elizabeth Wathuti told adults gathering in Glasgow for COP26, “Sub-Saharan Africa is responsible for 0.5 per cent of historical emissions; the children are responsible for none”. Intersectionality makes of youth-led litigation a global vanguard in the fight for climate justice, which is above all justice for the Global South, regardless of who pursues it and where.

Youth-Led Litigation’s Evolving Geography

Youth-led climate litigation has a little more than a decade of history behind it. The Supreme Court of the Philippines decided the iconic Minors Oposa case, which also concerned the greenhouse effect of deforestation, as early as 1993. However, that ruling belongs to a different epoch, one far less beset than ours by the riddle of climate justice and where nothing resembling today’s youth movement against global warming existed. It was then in the United States in the early 2010s, that youth legal activism against global warming as we know it today took root before spreading worldwide.

Starting in 2011, Our Children’s Trust (OCT), a non-profit public-interest law firm based in Oregon, undertook a “strategically coordinated national effort” to file complaints with courts in almost every state (for a detailed survey, see here). Most of these actions failed either because they were considered precluded by separation of powers or because they sought to expand the scope of the public trust doctrine in ways that many courts found unconvincing. OCT – which has strived to disseminate its litigation model worldwide – now mostly concentrates on Juliana v US, a case involving 21 youths and pending before the Federal courts of Oregon since 2015.

Apart from a complaint filed in 2012 with the High Court in Kampala, Uganda, and still pending, the US maintained a monopoly on youth-led climate litigation until 2013, when the Netherlands joined it on the map. In 2016-2018, cases emerged in New Zealand, Norway, the UK, Ireland, Canada and, in the Global South, in Pakistan, India, the Philippines, and Colombia, where youth collected what is arguably their most significant victory to date. In 2018, international litigation involving young people debuted before the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which notoriously declared the action inadmissible. That was also the first case formally possessing a transnational dimension, as the plaintiffs included non-EU citizens.

The period 2019-2021 kicked off with the multistate case filed before the CRC. It continued with litigation intensifying in Canada, Australia’s awakening after the Black Summer, a boom in Latin America, with new cases emerging in Peru, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, Guyana and Haiti, this last brought before the Inter-American human rights system. Cases arose also in South Korea and South Africa. Meanwhile, international litigation went on in Europe, with two cases lodged with the Strasbourg Court, one against 33 states, the other against Norway (which is a defendant also in the former case). Complaints were filed also in Italy, Spain, Poland, and again in the UK, but especially in Germany, which seems to have inherited the role of youth-led litigation hub.

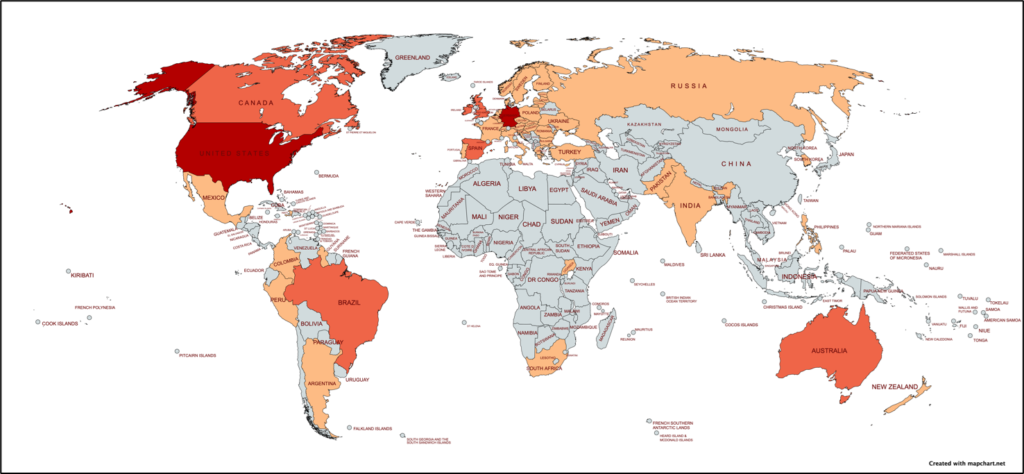

The map shows how much youth-led climate litigation has affected individual states by considering how often they were sued. The light shade indicates states that were (or are) defendants in fewer than three cases. The dark shade signals 10 cases or more. The intermediate shade covers the rest.

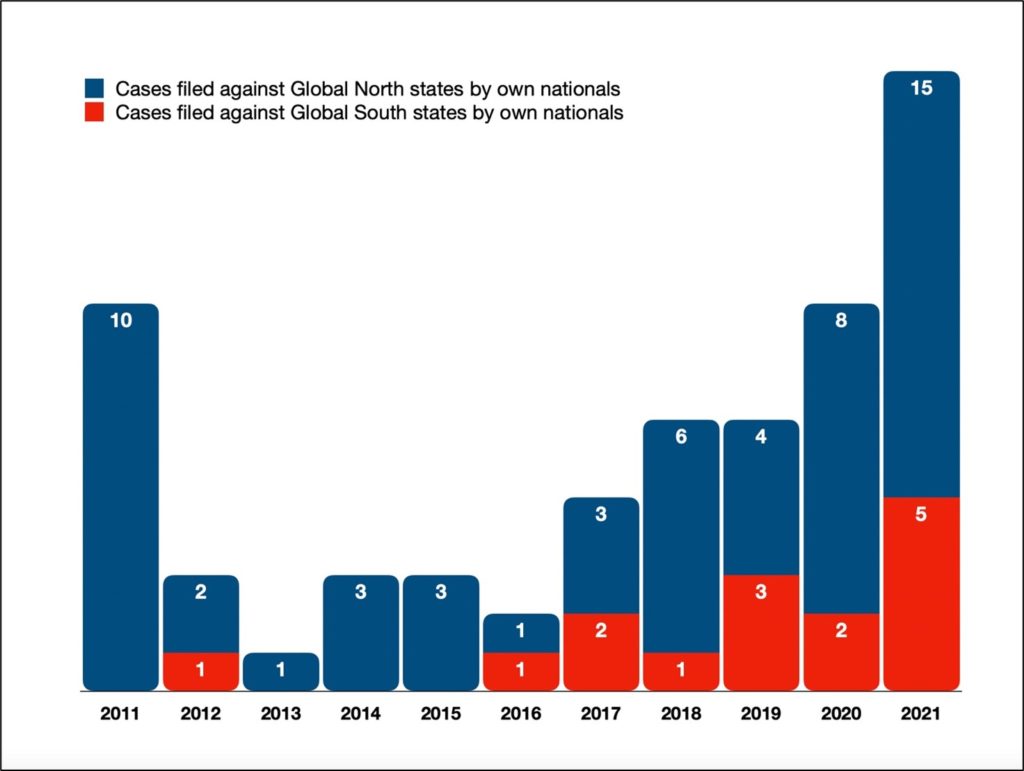

Until 2017, individual cases have been essentially domestic, meaning that the plaintiffs were invariably all nationals or residents of the forum state (we say “essentially” because, in a way, climate litigation always straddles borders, as do the adverse effects that it seeks to offset do).

Chart 1 reflects the distribution of such domestic complaints over time (by date of filing) and across the North-South divide. Within the category of “domestic complaints” we also included those lodged with an international adjudicative body against the country of which the plaintiff is a national or resident.

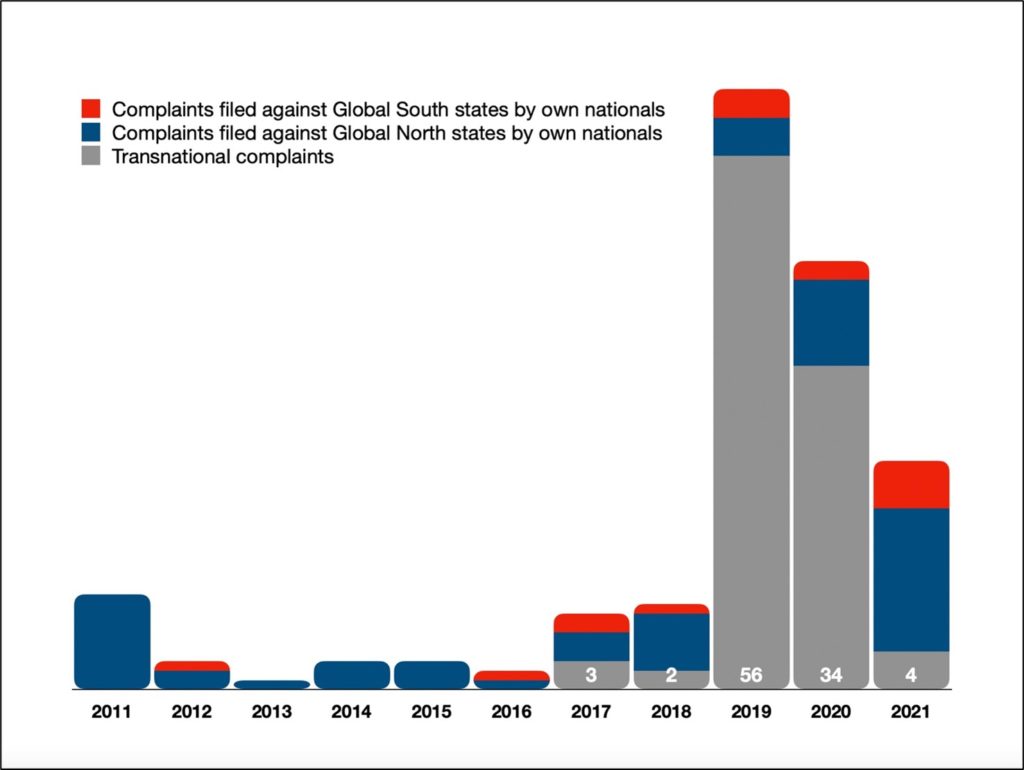

As Chart 2 shows, in 2019-2020 there has been a spike in transnational complaints (i.e. brought by foreigners), largely driven by the structure of the multistate complaints brought before the CRC and the Strasbourg Court. The drop in 2021, as we shall see, may not be entirely accidental.

Transnational Geometries

In order to provide a nuanced view of the phenomenon, we gave the concept of “transnational complaint” a broad and informal meaning. In it, we included cases where a petitioner is either a national or resident of a state other than the forum state or has a diaspora or temporary migration background, provided that the complaint shows concern about the effects of climate change on living conditions in the country of origin. Two cases filed in 2017 and 2021 with UK courts by the London-based charity Plan B and several young petitioners are illustrative of this point.

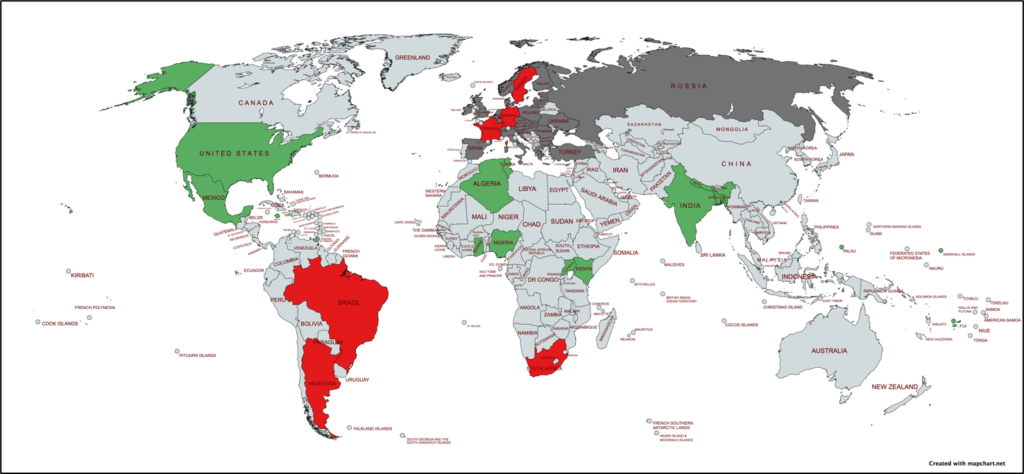

In an application for permission to appeal lodged on 27 December 2021, the petitioners point out that “young people […] with families in the Global South are exposed to disproportionate and discriminatory risk” (here, at para. 76). Taken together, these cases feature ratione personarum links with Algeria, Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, and Jamaica. Transnational complaints were also brought before the CJEU (applicants in the so-called People’s Climate Case include citizens of Fiji and Kenya) as well as before the German Constitutional Court (Yi Yi Prue et al. v Germany, joined to the better-known Neubauer, involves citizens of Bangladesh and Nepal).

The map shows the geography of transnational claims, marking states sued by foreigners (in the above-mentioned broad sense) in dark grey, states from which such claims originate in green, and states falling in both categories in red.

The transnational dimension is most notably present in cases brought before international bodies. With plaintiffs hailing from 12 different countries and five defendant states, Sacchi et al. v Argentina et al., the case the CRC dismissed, breaks down into a bundle of 56 transnational complaints (counting only once complaints coming from the same country), 34 against the Global North (of which 10 intra-North) and 22 against the Global South (of which 14 intra-South).

As Chart 3 shows, transnational complaints against states in the Global North are prevalent. North-versus-North complaints are more numerous than South-versus-North ones because of Duarte Agostinho et al. v Portugal and 32 Other States, the multistate intra-North case brought before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) by Portuguese youths. It is worth noting that this complaint originates from a state with a relatively low per capita income and an emission record that is not nearly as bad as that of many other states in the Global North. But the picture would change if, in calculating Portugal’s historical contribution to climate change, its long-standing role as a colonial power were factored in.

In this regard, it is noteworthy that, in an international setting where consensus on criteria for apportioning the burden of climate change mitigation remains elusive, even young petitioners seem to hesitate between historical and current emissions. The plaintiffs before the CRC relied on the latter criterion. They selected the five largest current emitters from among the 47 states then bound by the Additional Protocol, with the sole exception of France, which would be in sixth place after Italy (by a small margin) but enjoys higher international standing. The Portuguese youths, by contrast, applied the former criterion. Among the 47 states parties to the ECHR, they first picked the EU Members en bloc (which is why even Malta is on the list) and then singled out the other six defendants based on historical emissions, as evidenced by the fact that three state parties not sued – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Azerbaijan, a small oil power – currently emit more than at least one of the six selected (we relied on Our World in Data).

Foreclosing Transnational Complaints?

The strategy of challenging a plurality of states directly before international adjudicating bodies has been, so far, a youth’s distinct move in the field of climate litigation, and it is by far the largest vehicle for transnational complaints. As is known, that strategy failed at the CRC, which reaffirmed the importance of engaging domestic courts first, “because pathways to justice must be built from the ground up” (see here, at 3). The petitioners were right to point out that a multistate claim would have certainly failed domestically, because of foreign state immunity. However, the CRC sidestepped the objection by noting that such claims create themselves the problem of immunity and are not “necessary to bring effective relief” (see here, para. 10.18). It will be interesting to see whether the ECtHR will follow the CRC in the multistate case pending before it.

Be that as it may, the reasoning by which the CRC dismissed the multistate case does not apply to transnational complaints against single states. As already noted, there are as many as 56 such claims nested in the communication filed by Ms. Thunberg and her associates. Now, the CRC encouraged transnational complaints insofar as it established that any state that fails to prevent greenhouse gas emissions compounds a climate crisis that may result in human rights violations anywhere in the world, especially at the expense of children (see here, at 2). Professor Wewerinke-Singh persuasively argued that the CRC should have declared the transnational claims made by Marshallese children admissible on grounds of urgency. However, on closer inspection, the CRC should have in principle admitted all the 56 transnational claims, because the defendant states emphatically rejected the notion that they could be held responsible for human rights violations that climate change may cause on the territory of other states (see, e.g., Germany’s position at paras 4.7 and 7.4).

Of course, domestic courts may not share the government’s opinion and instead follow the CRC’s guidance on this issue. However, the Neubauer judgment, delivered by the German Constitutional Court months before the CRC’s ruling, points in a different direction. For the Court, the claims made by nationals of Nepal and Bangladesh were non-justiciable (see here, at paras 173-181). The German government’s position and the Court’s differ. For the government, the state’s lack of jurisdiction over transnational claims is obvious and incurable. For the Court, the matter is not so simple, but for all practical purposes the outcome is the same and the judgment has seemingly already produced a chilling effect on such claims: none of the eight post-Neubauer constitutional complaints includes foreign youth among the applicants.

Ways Ahead

The CRC’s dismissal of Sacchi et al. v Argentina et al. caused understandable disappointment among young climate activists. However, the CRC’s opinion is not without wisdom, insofar as it promotes extensive recourse to domestic courts, whose rulings are likely to be more influential than the CRC’s, especially vis-à-vis national governments. At the UN level, it is unlikely that the Human Rights Committee (before which further major emitters could be sued) would treat the exhaustion of domestic remedies differently. As for the ECtHR, however it settles the matter, it is still a regional court. Has the CRC’s ruling shattered the dream of a global trial against adults who do not obey Lovejoy’s Law?

Barring an ecocide trial before the International Criminal Court, the closest one can get to realising such a vision is having advisory proceedings at the ICJ, where young people could address the bench as co-counsels for states most affected by climate change. WYCJ is wise to pursue this initiative and it may well find not a few allies among states of the Global South. Meanwhile, the global youth movement, in addition to attending adult-dominated COPs, should perhaps organise its own meetings to discuss and set parameters for allocating mitigation burdens among states. It should be clear by now that, despite Lovejoy’s Law, intergenerational love does not yield equity.

Solidarity with those who suffer most from the negative impact of global warming is more likely to emerge from an assembly of young people, in which, if only for demographic reasons, demands from the Global South should carry overwhelming political weight. If, unlike adults entangled in all sorts of interests, youth can agree on a general scheme for emissions reduction, that scheme could serve as a touchstone for coordinating claims before national courts. Once complaints concerning emissions reduction targets – which are now prevalent – come to incorporate Global South’s viewpoints, there would be no need to involve foreign claimants: youth in the North would defend the interests of their counterparts in the South based on a global compact on the allocation of mitigation burdens.

The CRC’s ruling may have encouraged youths from the Global South to file transnational claims with domestic courts in the North, but a powerful institution like the German Constitutional Court disallowed such actions. Since the risk of seeing them rejected is high, it may be worth taking it only if plaintiffs from the Global South seek compensation for the damage caused by abnormal weather events, instead of joining in the claim for prospective remedies, which local plaintiffs can press by themselves in accordance with the compact. Wealthy backers of climate litigation could support the filing of such cases on an experimental basis, helping Global South youth to sue for damages states with dismal emission reduction records and, why not, private corporations as well.

Disclaimer: Maps (created with Mapchart) and charts are the authors’ work.