On Tables, Markets, and Free Speech

What to Do with Digital Private Censorship?

There is likely no other piece of furniture that would be as ungrateful, frustrating but at the same time illuminating as tables (although when it comes to illumination, lamps are quite successful). This is because tables have a natural tendency to turn.

One day Big Tech decides to ban Donald Trump, met with applause by those who do not support him. Then, tables turn and Twitter is taken over by Elon Musk. Some people are now upset, because Twitter’s power can be used against them; other people are cheerful, because someone else is now getting banned.

When tables turn too quickly it is easy to lose balance and a broader perspective on what happens around us. And what happens in the area of market regulation and free speech is interesting both from the point of view of constitutional issues (the “Verfassung” question) and economic arrangements that drive European economies (the “Wirtschaftsverfassung” question).

On the surface level, we see private actors exercising more and more power over speech; on a deeper level though, we might be returning to a far older discussion about the interplay of private and public power, and the fate of an individual who lives in the crash zone between them. Given that the result of this clash largely comes down to choosing a proper regulatory policy, this contribution argues that when regulating market-situated speech, particular caution should be exercised.

Private Censorship

Almost two centuries after the publication of a once widely read manifesto, one could say that a spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of what some call “populism”. Hungary and Poland used to make headlines in this area, but with the success of Geert Wilders in the Netherlands, and the growing popularity of AfD in Germany, the focus might soon change.

Exiled from traditional media, both alt-right and alt-left found refuge in social media. From there, they started a long march towards political relevance. In 2015-2020, social media begun to modify their content moderation policies in a way that became less hospitable to those refugees. In Europe, Poland might serve as an example: when Facebook started applying a stricter content moderation policy, this resulted in takedowns targeted at information spread by Polish alt-right activists – most notably, so-called “Independence Marches”, organised annually on the Polish Independence Day. Private censorship concerns started to be voiced. Trump’s 2021 social media bans can be taken as a culminating point of this broader global trend. While many mainstream commentators welcomed bans imposed on “populists”, the reaction of even mainstream political leaders was more ambiguous – some suggested that social media should be regulated.

This sentiment became even stronger when Musk’s takeover of Twitter showed that the power of Big Tech can be exercised in various ways, not just by banning the “populists”.

Indeed, while arguments can be made that censorship is a government issue, the boundary between public and private censorship is thin. To see this, one can imagine a more far-reaching development than Musk’s takeover of Twitter. Assuming that Elon Musk accomplishes some day his dream of colonising Mars, would it matter if SpaceX started censoring people in its corporate, Martian mining town? Clearly, the colony would not be a state, at least not until it decided to “dissolve the political bands which have connected” it to Earth and became a state itself. Yet, “intuitively” many people would likely say that this is censorship. And indeed, while this Mars story might seem like science-fiction, it did happen – in a way. In the 1940s, in a case coincidentally known as Marsh, an individual was attempting to distribute leaflets in a corporate town in the United States, but was prohibited from doing so. The US Supreme Court decided that the corporate town was not in a position to impose such a prohibition and that free speech guarantees did apply to a private actor. Since that time, this approach has been (largely) dropped, and in Europe it never gained prominence, but current controversies over private censorship may change this dynamic – and not without some logic. However, developing an approach towards market-situated speech is not easy.

Market-Imposed Restrictions

Governments have incentives to censor speech. What about corporations? Three group of reasons might incline them to do so: two are more extreme and possibly easier to assess; one is more ambiguous.

First, censoring – or more technically “restricting the flow of information” – might be motivated by profit-making. Showing certain kinds of information might decrease profits as consumers are not interested in some information, or even find it repulsive. Twitter provides a good example as shortly after Elon Musk’s takeover, fake accounts were created and started posting parody tweets. While possibly amusing to some users in a short-run, one could expect that in the long-run, a large amount of this kind of information would decrease the value of service to users. While some might call this “censorship”, there seems to be little or no controversy with this kind of information suppression, even by dominant platforms.

Second, corporations might restrict information flows for malicious reasons, e.g. anticompetitive reasons. After Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, it was reported, for instance, that Twitter contemplated banning links to Mastodon, which at that time seemed like a potential competitor. In a far more distant past, the Associated Press was prosecuted under antitrust laws in the United States in connection with its bylaws, which prevented non-member newspapers from obtaining news. It was argued within the US Supreme Court that while seemingly economic, the case had also a deeper free speech dimension that required a more nuanced assessment under antitrust – a sentiment still alive a few decades later.

There is far more ambiguity about the third group which can be called “moral issues”. Corporate actions can be seen as merely profit-driven. In the 1970s, when opposing corporate social responsibility, Milton Friedman famously claimed: “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits”. Nowadays, this is equally or even more controversial than before the rise of neoliberalism. On the one hand, there is a strong push towards CSR. On the other hand, the “political correctness” of corporations may motivate free speech restrictions – and if taken as a principle, this may lead to bans imposed on individuals of various political convictions. After all, it is the corporate entity that decides at the end of the day which views it finds politically correct.

Speech, Information, Discovery

There are various tools and options to provide a counter-balance towards the power of Big Tech over speech. An extreme option would be to extend the so-called public forum doctrine to private actors. Another route, one seemingly preferred today, is regulation – it is not only mentioned by politicians but speculated even within the US Supreme Court. One might also think about antitrust enforcement: big news in the United States during the 2020 presidential elections, but somehow less of a topic in Europe.

One may also decide to do nothing – yet, even in this case, the topic causes controversy. For instance, fake news are already an issue today, but further problems might soon appear with regard to information warfare (as opposed to merely “somewhat” weaponised fake news), deep fakes, and AI-generated content. Businesses could decrease their costs in dealing with these types of information through cooperation – in fact, to some extent, they already do – but this poses a question of when such cooperation becomes too close, and possibly anticompetitive.

Navigating this complex area may require more dialogue between market regulation experts and lawyers more accustomed with human rights and constitutional perspectives. This is even more so when one realises that there are surprising parallels between free speech and free markets.

Free speech is often justified under an argument known as the “marketplace of ideas”. The argument is that there is more use in having arguments and opinions heard than to stifle them, even if they are false. In short, free speech is seen as a discovery method. A similar logic is used in relation to the market economy. In his seminal 1945 article “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, Friedrich Hayek argued that the “market” is ultimately a discovery method that allows information-processing: this discovery function is performed well in competitive markets, yet not under central-planning. However, Hayek also noted that in between there is the issue of monopoly, about which “many people talk but which few like when they see it”.

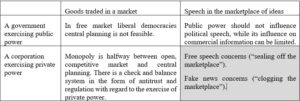

Against this backdrop, the market and free speech issue can be seen in a following way:

The question is how to arrange the last of this issues – and one might be willing to be careful when moving around this matrix so that unchecked private power is not replaced with public dirigisme.

Who Decides?

In reaction to Elon Musk’s takeover of Twitter, Shoshana Zuboff expressed her dissatisfaction and repeated the mantra-type of conclusion from her research on surveillance capitalism: “who decides?”. Her view was that such things as free speech should not be decided on the whims of individuals, and that the democratic rule of law is needed.

Yet, free speech in a market context is a complex subject. On the one hand, markets are inherently “democratic” institutions, where each day consumers express their preferences. On the other hand, the study of market regulation, like antitrust, informs us that markets can be corrupted, entrenched, and may underdeliver.

This ties back to Zuboff’s “who decides?”, but in a different way. The “who decides?” question is old: it became one of central issues during the political and economic revolution brought by neoliberalism in the 1980s. It comes down to striking the right balance between decisions influenced by public and private power. To some extent this is a political question, influenced by one’s political preferences that are beyond the realm of “scientific” proof. Yet, it is also a more technical question of designing social systems in a way that provides optimal levels of feedback, responsiveness, and adaptability. This might be the true conundrum of liberal democracy: laying down a system that in a long term cancels out power: power of each branch of government in relation to other branches of government; power of each economic actor in relation to other economic actors; and public-private power in relation to each other; yet all of that without creating a feeling of hopelessness.

Using legal instruments in the area of market-situated free speech is particularly difficult: not only we are speaking about regulating spontaneous market interactions, but we are doing so in relation to speech-related interactions, i.e. we are regulating two information-processing systems at the same time. Given the complexity of this problem, one may be willing to opt for an approach that provides counter-measures against most extreme uses of private power, but which does not result in a substitution of generally spontaneous processing of information with public decision-making: black oceans of uncertainty when it comes to specific results, but navigable enough when it comes to general frameworks to avoid storms. In practical terms – and going back to the topic of tables, which started this article – an option on the table could be limited forms of regulation (e.g. introducing accelerated court procedures to verify bans imposed on politicians and political content during elections) and antitrust enforcement ensuring that markets are competitive.