Stronger Together

On the Value of Collective Bargaining Autonomy

Yesterday, we marked 1 May – International Workers’ Day. The roots of this bank holiday stretch back to 1889, when the first “great international demonstration” was called for 1 May 1890. Its key demand: to fix the working day at eight hours. The limitation of daily working time was a hard-won gain – achieved through decades of struggle – to safeguard the health and dignity of working people. Now, 135 years later, the eight-hour day is once again under threat – this time through the newly negotiated German coalition agreement.

And that’s only one of several contentious labour policy issues the new conservative-social democratic coalition has brought to the table. Public debate, however, has largely centred on the coalition’s shared commitment to raise the statutory minimum wage to €15. On the one hand, this is a crucial measure to protect workers not only in low-wage sectors. On the other hand, the political focus on the minimum wage reflects a deeper malaise: the weakening of trade unions and the collective bargaining system. It is no coincidence that, twenty years ago, even within the DGB (German Trade Union Confederation), there was no consensus about the need for a statutory minimum wage. IG Metall (Industriegewerkschaft Metall, Germany’s largest trade union), for instance, stood apart from unions like ver.di (Vereinte Dienstleistungsgewerkschaft, United Services Union, representing a huge diversity of service-sector workers) and NGG (Gewerkschaft Nahrung-Genuss-Gaststätten, Food, Beverages and Catering Union, one of the oldest unions in Germany, known for representing vulnerable, often precarious workers), which eventually prevailed after an extensive public campaign. It was not until 2015, after all, that Germany introduced a national minimum wage.

The reasons for that earlier hesitation echo those voiced more recently by the Danish and Swedish governments, which – in full alignment with their own unions – voted against the EU’s 2022 Minimum Wage Directive. They’ve since filed a legal challenge, objecting, inter alia, “on principle” to parts of the directive that, in practice, do not even apply in their countries (see para. 35 of the Advocate General’s opinion). The principle at stake? That minimum pay should be determined by collective agreements, not imposed by the state. This same principle – the primacy of collective bargaining autonomy – forms the foundation of German labour law. As Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court puts it (para. 144): “The fundamental right to collective bargaining autonomy guarantees a space in which workers and employers may negotiate their conflicting interests on their own responsibility.”

The significance of collective bargaining autonomy for a democratic society can hardly be overstated. In a functioning democracy, people should not spend their working lives feeling like their voices do not matter. The ability to help shape one’s own working conditions, to resist exploitation, to fight for better work – that is what social policy in a democracy is ultimately about. And that requires collective organisation. The Nazis understood this well. That’s why, one day after 1 May 1933, the SA and SS stormed union halls, dissolved free trade unions, and arrested their members. Against this historical backdrop, Article 9(3) of Germany’s Basic Law guarantees not only freedom of association and the right to strike, but also the autonomy of collective bargaining, unconditionally.

It is precisely because collective organisations are no longer capable of ensuring decent minimum working conditions on a broad scale that the minimum wage has become so central. In 2009, then Labour Minister Olaf Scholz failed to foster collective bargaining without resorting to a statutory minimum wage, through revisions to the Posted Workers Act and the Minimum Working Conditions Act. In 2014, Andrea Nahles succeeded in doing just that, introducing the Minimum Wage Act with the stated aim of strengthening collective bargaining.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++

Das Open Research Office Berlin sucht für drei Jahre eine Volljuristin (w/m/d) mit Schwerpunkt Urheberrecht (Projektförderung durch die VolkswagenStiftung). Wir bauen ein Legal Helpdesk für Open Research auf, um Angehörige der Berliner Wissenschafts- und Kulturerbe-Einrichtungen juristisch zu unterstützen. Im Zentrum der Stelle stehen die juristische Beratung der Forschenden (v.a. Urheberrecht, teils auch datenschutzrechtliche und arbeitsrechtliche Fragen), die Erarbeitung von politischen Positionspapieren sowie Open Educational Resources (OER) für juristische Laien****.

Mehr Informationen hier.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

But why has collective organisation become so weak? The answer, unfortunately, is complex. Multiple factors reinforce each other. The cultural environments in which union membership was the norm – where it was tied to a sense of belonging within a diverse working-class culture – have largely disappeared. Values and social ties have shifted. Today’s “society of singularities” is inhospitable to organisations that emphasise solidarity and collective identity. At the same time, new precarious and migrant worker communities – often willing to fight – tend to organise outside traditional union structures in Germany.

Is collective bargaining autonomy, then, like democracy in the Böckenförde paradox – dependent on social conditions it cannot itself guarantee? The Constitutional Court seems to think so: “A union’s level of organisation, its ability to recruit and mobilise members, and similar factors lie outside the responsibility of the legislator” (paras. 111, 21). But the court adds an important caveat: The legislator is may correct disparities that are “structural in nature”.

Yet structural disparities clearly exist, not least because employers hold considerable leverage through control over production, investment, location, and jobs (para. 32). Much of the decline in collective organisation since the 1990s is structural in this sense: the result of economic restructuring encouraged or facilitated by legislation and court rulings. Social milieus are intertwined with economic structures and evolve with them. Outsourcing, privatisation, corporate fragmentation, the shift from industry to services, digitisation, remote work, and increasingly flexible employment arrangements (fixed-term contracts, agency work, subcontracting) have all played a role. Unions have a harder time organising in small service-sector workplaces. Social ties are thinner, collective power is weaker, and the personal risks of taking action are greater. A worker on a temporary contract in a small retail shop earning poverty wages is unlikely to have the resources or protections to challenge their boss – or even their supervisor. Especially since employer resistance has grown stronger. Fewer companies are willing to join employer associations and participate in collective agreements. The membership, without bargaining obligations has normalised and legitimised this retreat. Increasingly, companies follow the lead of their American investors, actively opposing collective worker action. Union busting – in the form of obstruction of Works Councils – has spread in Germany, too.

The result? Collective bargaining coverage in Germany has dropped from 67% in 1996 to just 49% of workers in 2024, with figures having stabilised in recent years. The need for a new law to strengthen collective bargaining autonomy is undeniable.

In fact, a range of well-coordinated and strategically important proposals have been developed in recent years – some already as draft laws, such as for union member benefits through so-called “favourability clauses”. Encouragingly, the current coalition agreement (p. 18) takes up several of these ideas – including the “Federal Fair Pay” initiative, first introduced under the previous government. The plan is to ensure that public contracts are awarded only to firms bound by collective agreements (albeit in a more limited form than envisioned by the previous government). Other measures include support for the “Fair Mobility” counselling network for migrant workers, digital access rights for unions to reach workplaces and employees, and tax incentives for union membership.

These are welcome initiatives. However, the public should keep an eye on their implementation. For collective organisation and action will remain necessary to prevent social policy setbacks. That’s why 1 May is not just a day of celebration – it’s still a day of struggle.

*

Editor’s Pick

by JANA TRAPP

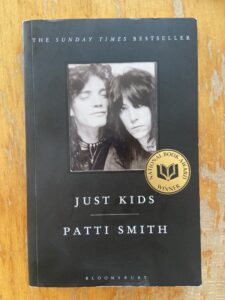

“I was just a girl, sitting in front of a typewriter, trying to write a novel.”

“I was just a girl, sitting in front of a typewriter, trying to write a novel.”

Gently, Patti Smith draws me into a story about creative innocence and the first tender bonds of love, while also reminding us that often, in the most uncomfortable moments and in the most pleasantly chaotic places, our transformation quietly begins.

Patti Smith’s memoir about her years in New York and her relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe is filled with tender yet courageous truths about the tireless search and the longing to become. What moves me most about Just Kids is not just the poetic depiction of a young woman’s artistic journey, but also the sincerity with which smith captures the unfinished and uncertain aspects of life. To me, her narrative is an ode to growing through doubt and trusting in one’s own voice – and to those romantics who never die.

*

The Week on Verfassungsblog

summarised by EVA MARIA BREDLER and JANA TRAPP

“I run the country and the world,” said Trump in an interview with The Atlantic. While this may sound like his typical megalomania, it may be surprisingly close to the truth for Trump’s standards, especially when you look at this week’s pieces.

He runs the universities: For weeks, the Trump administration has been attacking universities with funding cuts and blackmail, firing staff, deporting students, declaring programmes on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” illegal, and announcing “measures against anti-Semitism”. Now, the U.S. government claims that Harvard and other universities violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, labelling them as “breeding grounds for anti-Semitism”. HANS MICHAEL HEINIG (ENG) explores what this teaches us about academic freedom.

He runs the global economy: The Trump administration has ramped up average U.S. tariffs to 23%, a ten-fold increase from a year ago. How can one person have the power to single-handedly enact such sweeping changes to the global economy? The short answer: He probably may not – and, according to TIMOTHY MEYER (ENG), does not have the power to impose most of his tariffs.

He runs the legal profession: Trump is attacking the legal profession and blackmailing major law firms into cooperation – a pact with the devil. Could that happen in Germany, too? How well are lawyers in Germany protected? Not well enough, argues MAXIMILIAN GERHOLD (GER), who proposes protecting the legal profession in the German Constitution.

More protection is needed against gender-based violence, too. To that end, the new German coalition agreement focuses mainly on criminal and security policy measures. HANNA WELTE and PATRICIA GEYLER (GER) argue that the government’s plans only address symptoms, not the root causes, and leave structural inequalities unchallenged.

The coalition agreement also seeks to tighten the law on incitement of masses under Section 130 of the German Criminal Code, while simultaneously removing the right to vote for individuals repeatedly convicted of incitement of masses. ELISA HOVEN (GER) warns that this could have far-reaching consequences for political participation as well as trust in the rule of law.

Speaking of trust: In Indonesia, newly elected President Prabowo Subianto is losing exactly that. Nationwide protests are erupting against his erosion of democracy and the rule of law. For RATU NAFISAH (ENG), the “Dark Indonesia” protest movement highlights the importance of civil society in safeguarding a country’s democracy.

How resilient is trust? While fundamental principles are once again being violated in Turkey, Germany remains conspicuously silent. SANDRA SCHERBARTH and NOAH KISTNER (GER) call for the principle of mutual trust in extradition law to no longer be treated as an unquestionable doctrine, and for extraditions to be temporarily suspended.

As the reliability of the rule of law is called into question in Turkey, the term “hate speech” also reveals its malleability depending on political context. The criminalization of boycott calls by Turkish authorities highlights this flexibility. AYTEKIN KAAN KURTUL (ENG) examines this case as an example of geopolitically motivated double standards, with broader implications for global human rights protection.

The CJEU recently ruled on who belongs to civil society – specifically, whether one can “buy” a place in it. With its landmark judgment in Commission v Malta, the Court shut down the “commercialisation” of Union citizenship, effectively fighting corruption. SIMON COX (ENG) analyses what this historic judgment means for the future of so-called Golden Passports.

The Estonian Parliament decided not tinker with citizenship, but one of the most fundamental rights associated therewith: Since March, Russian nationals in Estonia are not allowed to vote in local elections due to national security concerns. RAIT MARUSTE (ENG) explains the recent constitutional amendment and the historical context behind this firmly non-partisan decision.

All eyes are also on Luxembourg, where the CJEU is once again addressing the impact of Poland’s judicial reform. GIULIANO VOSA (ENG) sees the Advocate General’s opinion as a symbol of the EU’s political timidity and the erosion of the rule of law in the face of multiple ongoing crises.

A different recognition issue arose in Wojewoda Mazowiecki – a case concerning the recognition and transcription of a same-sex marriage legally contracted in one EU country between two nationals of another EU country. In his opinion, Advocate General de la Tour calls for the recognition of such marriages across the EU. FULVIA RISTUCCIA (ENG) unpacks the Opinion and demonstrates where the AG could go even further.

Did France go too far, though? In 2024, the French government imposed a TikTok ban in Kanaky-New Caledonia amid civil unrest. Now, the Conseil d’État has reviewed the ban. MARIE LAUR (ENG) reveals the colonial legacies that the French TikTok ban in New Caledonia exposed.

Maybe France acted too close to megalomania, too. As for Trump, the Public Religion Research Institute’s new poll concludes, “Americans largely oppose President Donald Trump’s actions during his first 100 days in office. Most notably, a majority (52%) of Americans agree that ‘President Trump is a dangerous dictator whose power should be limited before he destroys American democracy.’”

He may not run universities: More than 400 university presidents have signed a letter, declaring to “speak with one voice against the unprecedented government overreach and political interference now endangering American higher education” and sharing “a commitment to serve as centers of open inquiry where, in their pursuit of truth, faculty, students, and staff are free to exchange ideas and opinions across a full range of viewpoints without fear of retribution, censorship, or deportation.”

He may not run the global economy: Some U.S. exports are already being crushed by Trump’s tariffs backfiring.

He may not run the legal profession: Lawfare counts 255 lawsuits against the Trump administration, and law students at Georgetown are tracking law firms, sorting them into five categories: “Caved to Administration,” “Complying in Advance,” “Other Negative Action,” “Stood Up Against Administration’s Attacks,” or “No Response.” Reportedly, they are declining to join the cavers and compliers.

*

Take care and all the best!

Yours,

the Verfassungsblog Team

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an email, you can subscribe here.