Quantifying Fair Share Carbon Budgets

The Margin of Appreciation in the ECtHR’s Klimaseniorinnen Judgment Revisited

Writing in Verfassungsblog in April 2024, shortly after the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) landmark climate judgment in KlimaSeniorinnen, Chris Hilson argued that the ‘most ambiguous and potentially contentious part of the ruling relates to the Court’s discussion of “carbon budgets” (paras. 550, 569-573).’

The context was the Court’s interpretation of the margin of appreciation – the level of deference the ECtHR will grant to a State – in the context of climate change. Here, the Court drew a distinction between the reduced margin of appreciation for States when setting ‘the requisite aims and objectives’ in respect of the State’s commitment to the necessity of combating climate change and its adverse effects, and the wide margin of appreciation States have in choosing the means designed to achieve those objectives (para. 543).

While describing the point as ‘ambiguous’, Professor Hilson ultimately concluded that ‘the [ECtHR] associates the issue of [carbon] budget setting with a wide margin of appreciation’. The purpose of the present contribution is to put the alternative view. Namely, that the setting of a particular national carbon budget represents the setting of ‘the requisite aims and objectives’ to combat climate change and its adverse effects, to which a reduced margin of appreciation applies, rather than simply being ‘the choice of means designed to achieve those objectives,’ where a wide margin of appreciation would apply (para. 543).

Professor Hilson’s analysis is based on carbon budgets being ‘used in two senses in the climate law and policy world.’ In the first sense, ‘they can, like the United Kingdom’s carbon budgets simply lay out a cap or maximum level that GHG emissions must be brought below in order to meet the climate targets that a state has set.’ In the second sense, the remaining global carbon budget associated with a particular global average temperature increase – 1.5°C, say – is calculated and then ‘divided up between states, in line with “fair shares.”’

In other words, under Professor Hilson’s analysis, a national climate target sets the aim or objective, with the national carbon budget simply laying out a cap or maximum level that greenhouse gas emissions must be brought below in order to meet the climate targets that a state has set. In our view, the relationship between climate targets and carbon budgets is such that the latter are never simply instrumental; rather, they always represent a choice between different aims and objectives.

To explain: a national climate target is typically a point-to-point comparison based on annual emissions in a country in two particular years: a baseline year and the target year. For example, in Ireland, the Climate Change Advisory Council was instructed by section 6A(5) of Ireland’s Climate Act to propose carbon budgets ‘such that the total amount of annual greenhouse gas emissions in the year ending on 31 December 2030 is 51 per cent less than the annual greenhouse gas emissions reported for the year ending on 31 December 2018’.

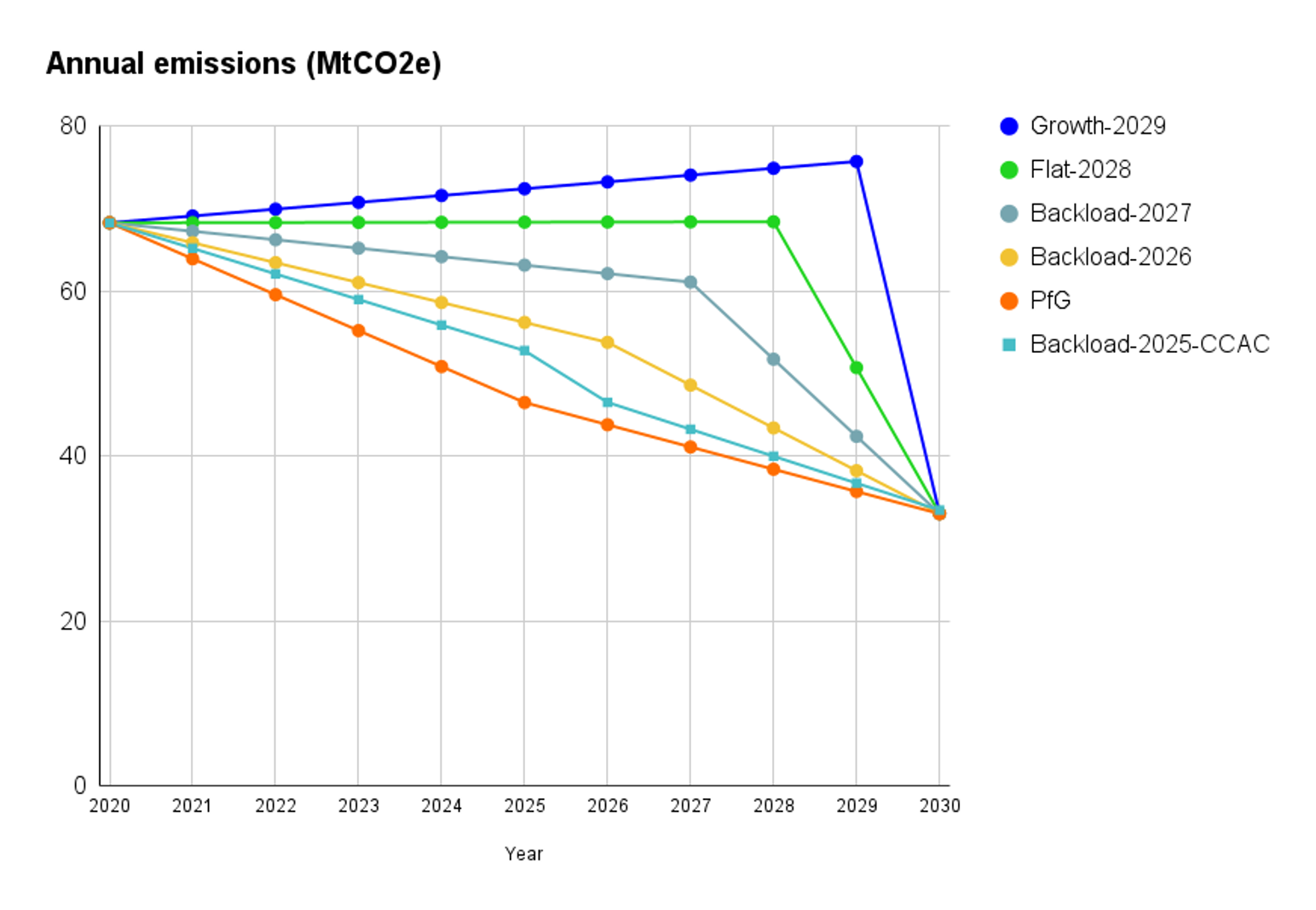

However, this instruction did not meaningfully constrain the carbon budgets that could be proposed and adopted, because there are lots of different pathways between Ireland’s annual emissions in 2018 and its annual emissions that are 51% below this in 2030, and each of these pathways has a different carbon budget associated with it. This is well illustrated by the Figure below: the carbon budget associated with each pathway (the area ‘under the line’ in each case) varies wildly.

Figure: Indicative emissions reduction pathways that are all notionally consistent with s.6A(5) of Ireland’s Climate Act (figure produced by Professor Barry McMullin).

In other words, a climate target sets the framework; it indicates what a country’s annual emissions are to be in a single year at the end of the period; it therefore sets an aim or objective in that sense, and ought to be subject to a reduced margin of appreciation per KlimaSeniorinnen. In turn, a carbon budget adopted within this framework also sets an aim or objective in KlimaSeniorinnen terms, because it is the budget that constrains the country’s contribution to climate change on a multi-annual basis. (Importantly, both targets and carbon budgets (or an equivalent method of quantification) are required by the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment: para. 550(a) and (b).)

A numerical climate target admits of and is equivocal between lots of different carbon budgets, each of which results in a different national contribution to global temperature increase. To put the point another way, the difference is between simply being given two points on a graph (the target, which compares annual emissions in two individual years) and being given the pathway that joins those two points (from which the budget can be calculated, constraining emissions for all years between the two points on the graph).

Since climate change is a problem of cumulative emissions since the beginning of the industrial revolution (Fig SPM.10 on p.18), carbon budgets are capable of constraining temperature increase in line with the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals, while climate targets alone are not. Further, in terms of the internal coherence of the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment, the alternative view, allowing States a wide margin of appreciation in the setting of national carbon budgets, would not be an approach to the ECHR that would ‘guarantee rights that are practical and effective’ (para. 545).

Thus, in our view, ‘the choice of means designed to achieve [a State’s climate] objectives’ (para. 543), to which a wide margin of appreciation applies, does not encompass the setting of carbon budgets, but rather captures policy choices such as which policies to adopt to decarbonise the energy system, how to reduce agricultural emissions, how to reduce emissions from transport, etc: these are the ‘operational choices and policies adopted in order to meet internationally anchored targets and commitments in the light of priorities and resources,’ of which the ECtHR speaks in its judgment in the context of a wide margin of appreciation (at para. 543).

It has been strongly argued by Dennis van Berkel et al in a recent contribution that, falling within the reduced margin of appreciation, KlimaSeniorinnen requires States to quantify a national fair share carbon budget that is set in relation to the remaining global carbon budget to limit heating to 1.5°C. In finding a breach of Article 8 ECHR in KlimaSeniorinnen, the ECtHR applied a quantification of a Swiss fair share carbon budget for 1.5°C (at para. 569), and rejected the argument put forward by Switzerland that its ‘national climate policy [which established targets] could be considered as being similar in approach to establishing a carbon budget’ (at paras. 570 and 360). As van Berkel et al note, ‘only a national carbon budget that is set in relation to the remaining global budget can be capable of mitigating the consequences of climate change, and thus practically and effectively protect human rights’ (cf. para. 545 of KlimaSeniorinnen). Notably, the Norwegian and Dutch National Human Rights Institutes have reached the same conclusion, as highlighted by a coalition of NGOs in their submission to the Committee of Ministers as part of the ongoing supervision of the implementation of the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment.

This obligation to quantify each country’s fair share of the remaining global budget to limit heating to 1.5°C will remain vital even as countries’ fair shares are used up (as will soon be the case for the European Union, for example, even on the ‘most lenient’ interpretation of fair share). This quantification will represent a line in the sand at a particular moment in time, calculated with reference to a particular baseline year. This will enable States to be held accountable, insofar as is possible, for their ‘carbon debt’, once their quantified fair share has run out. This seems likely to represent a new frontier in climate litigation in the not-too-distant future.

It must be recognised, however, that there are feasibility and sustainability concerns in terms of the amount of carbon debt that can be ‘repaid’ by way of net negative emissions, such that States’ primary focus should remain on rapid and deep reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the global average temperature decline as a result of net negative emissions (if achievable) is projected to be sluggish, and certain impacts will continue for many years. As the IPCC explains, ‘[i]f global net negative CO2 emissions were to be achieved and be sustained, the global CO2-induced surface temperature increase would be gradually reversed but other climate changes would continue in their current direction for decades to millennia (high confidence). For instance, it would take several centuries to millennia for global mean sea level to reverse course even under large net negative CO2 emissions.’

‘Gradually’ is the key word when it comes to reversing global temperatures: as Climate Analytics explains, ‘even under optimistic assumptions related to CDR [carbon dioxide removal] deployment and effectiveness, only about 0.05°C of global mean temperature increase may be reversible per decade.’

Barry McMullin et al thus argue that adopting a carbon debt framing ‘may help facilitate early nation-level societal discussion of whether, or how much, CO2 debt can or should be taken on, and the interaction of this with alternative pathways for earlier, deeper, mitigation of gross emissions which would allow that ultimate debt to be reduced or avoided altogether’. They conclude, ‘if large scale removal services prove difficult or infeasible to scale up, then this should prompt earlier and more severe limitation on the accumulation of CO2 debt.’

An obligation to quantify each country’s fair share of the remaining global carbon budget associated with limiting global heating to 1.5°C flows from the judgment in KlimaSeniorinnen. While there will naturally be debate about what represents a country’s fair share – the EU’s independent advisory body ESAB recently considered a range of fair share principles and concluded that the EU’s fair share has already been used up under many of these – the obligation to quantify fair share budgets should, in our view, be the subject of a reduced margin of appreciation consistent with KlimaSeniorinnen.