Laboratorium Lviv

Beyond Lethargy

As regular readers of Verfassungsblog will know, much of what we deal with revolves around various forms of crises: faltering democracies, weakened courts, and an international legal order that seems to be unravelling before our eyes. The stories you read here are rarely uplifting. It is important to tell them, but crisis narratives are not without their hazards. They can paralyse, obscure structural problems, and, over time, erode our imaginative capacities. Rather than encouraging fresh thinking, they push us onto the defensive and, in the worst case, lead to resignation and lethargy.

These reactions are understandable. Yet they do little to loosen the tightening grip of authoritarianism. So what is to be done? My suggestion: look to Ukraine. Shortly after the New Year, I travelled with Democracy Reporting International to Lviv, a western Ukrainian city of countless coffee houses and a rich history of international law. Amid the hum of generators and the blare of Christmas music, we spoke with many people who told us about the history of their city, the state of democracy, and their plans for the future. Lviv’s response to Russian authoritarianism is one of courage, connection, and defiance. It strikes me as deeply relevant far beyond Ukraine. And before 2026 once again pushes us into the defensive logic we have come to know all too well, I would like to begin the year on Verfassungsblog by turning our gaze to Lviv – and to what the city can teach us.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Applications are now open for the Institute for Law & AI’s Summer Research Fellowship (EU Law). This is a 10-week full-time fellowship that lasts from June 29 to September 4, 2026. Summer Research Fellows receive a €2,000 weekly stipend and work closely with LawAI staff at our Cambridge, UK office. We will consider remote candidates.

We welcome applications from law students, PhD candidates, and postdoctoral researchers with diverse skill sets, experience levels, and degrees of knowledge in AI law and policy. Applications close on January 30, 2026.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

The heart of international law

Just a short walk from the Lviv Opera stands a house with a small plaque commemorating one of the city’s most famous residents: Hersch Lauterpacht. The international lawyer and later judge at the International Court of Justice was the doctrinal architect of “crimes against humanity” and paved the way for its prosecution in Nuremberg. Lauterpacht studied at Lviv’s Faculty of Law between 1915 and 1919 and – as Philippe Sands uncovered in his groundbreaking book – shared some of the same teachers as Raphael Lemkin, himself a student at the University of Lviv and the originator of the term “genocide”. Lauterpacht and Lemkin decisively shaped twentieth-century international law. But what role does this legacy play at a time when elsewhere the death of international law is being proclaimed?

Lviv’s answer might be summed up as: now more than ever. “International law is not ending,” says Ivan Horodysky, co-founder of the Stanislav-Dnistrianskyi Centre for Law and Politics. “Moments of crisis demand intellectual renewal rather than abandonment.” Horodysky is one of the driving forces behind plans for a new centre for international law. Lviv, he argues, is predestined for this role – because of its history and because of Ukraine’s resistance to Russian aggression. His ambitions are considerable: the city is to become an “international hub” for international law – a place of research, reflection, and innovation. Such a centre would send a signal well beyond Ukraine’s borders. “It would show that international law is a living and adaptable tool,” Horodysky explains.

Lviv’s mayor, Andriy Sadovyi, is equally enthusiastic. “Lviv is the heart of international law,” he exclaims when I mention the plans for the new centre. He pledges his full support for the idea of such a centre and has no doubt that Lviv is the right place for it. After all, he says, Lviv is “a place for thinking.”

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Die Universität Kassel, Fachgebiet Öffentliches Recht, IT-Recht und Umweltrecht (Prof. Dr. Gerrit Hornung), sucht zum nächstmöglichen Zeitpunkt:

Wissenschaftliche:r Mitarbeiter:in (m/w/d), EG 13 TV-H, befristet (für 3 Jahre mit der Möglichkeit zur Verlängerung), Vollzeit (teilzeitfähig)

zur Mitwirkung in Lehre und Forschung, insbesondere in einem Projekt zur KI-Regulierung (Aufsicht über KI-Anbieter nach der KI-Verordnung)

Bewerbungsfrist: 30.1.2026; weitere Informationen im Ausschreibungstext.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Transformation and defence

Sadovyi’s enthusiasm for the centre is part of a broader constellation of projects, all revolving around resilience and renewal. Within just a few months, Lviv has built “Unbroken”, Ukraine’s largest rehabilitation centre. It treats those wounded and traumatised by the war, produces complex prosthetics, and supports reintegration into everyday life. An entire “ecosystem” has emerged there, Sadovyi notes. The centre is complemented by the international city network “Unbroken Cities”, established specifically for this purpose. The network aims both to support rehabilitation efforts in Ukraine and to allow others to learn from Ukrainian experience.

That there is much to learn from Ukraine is also emphasised by Svitlana Khyliuk, Dean of the Faculty of Law at the Ukrainian Catholic University. Khyliuk devotes much thought to how the Ukrainian constitution might evolve and break with its post-Soviet legacy. There is a strong desire to strengthen fundamental rights in the constitution; at the same time, numerous questions arise in relation to EU accession – such as what it means to join the Union while part of one’s territory remains under occupation. No other country, Khyliuk observes, has faced what Ukraine is currently undertaking: pursuing democratic reform at home while fighting off a large-scale invasion. Ukrainian lawyers are working under entirely unprecedented conditions – without templates, guidelines, or protocols. “We must transform ourselves as a country,” she says, “while, at the same time, continuing to fight.”

Whether in Lviv’s law faculties, its many cafés, or among grassroots initiatives led by young activists, plans are being drawn up, dreams articulated, and structures built. Like a small laboratory, the city is experimenting with strategies that move beyond resignation and lethargy. Not every experiment will succeed, and fear remains a dominant emotion here. Yet the tandem of transformation – understood as democratic reform – and defence against authoritarianism unquestionably provides an important point of orientation well beyond Lviv itself. “Only if we do not lose sight of the transformative element do we have a future,” Svitlana Khyliuk tells me at the end of our conversation. That is almost certainly true – in Lviv, in Ukraine, and very likely wherever you are reading this editorial.

*

Editor’s Pick

by EVA MARIA BREDLER

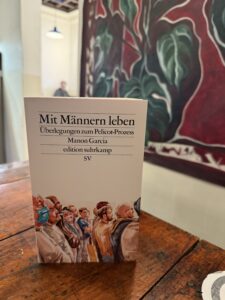

Gisèle Pelicot was drugged by her husband for almost ten years and raped by him and more than 70 other men. That sentence alone is hardly bearable. Garcia’s detailed account of the trial is painful to read, and yet her precise “Reflections on the Pelicot Trial” make the unbearable more intelligible. She exposes the continuum between incest and the rape of a woman who appears almost dead, the disturbing normalisation of such violence, and the seemingly endless objectification of women. Garcia writes not only as a philosopher, but as a woman in a world where these things happen. I cannot recall another reading experience so visceral: disgust, sadness, shame. It is a heavy but indispensable book – so that, page by page, the shame changes sides.

*

The Week on Verfassungsblog

summarised by EVA MARIA BREDLER

Every year, I find myself wondering what it really means to “get off to a good start in the New Year”. A fun New Year’s Eve? A satisfying reflection on the year gone by? Dodging the seasonal sniffles? Getting the tax return in on time?

On the world stage, however, it’s safe to say the year didn’t start well. On 3 January, US forces launched a surprise operation in Venezuela, capturing President Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores and flying them to the United States – a blatant violation of international law. BRAD R. ROTH (ENG) explains how the operation repudiates the UN Charter-based order – and why abandoning even hypocritical legal justifications is profoundly destabilising. ANDRÉ NOLLKAEMPER (ENG) adds that if such interventions become routine, it will be other states’ responses – especially Europe’s – that determine whether the erosion of international law is normalised.

Meanwhile, Europe seems to be normalising its own erosion of legality, as CHRISTINA ECKES (ENG) observes: Europe’s climate crisis is no longer just about emissions – it is also a rule of law crisis. In her piece, she shows how rollbacks on climate targets, sustainability law, and the combustion-engine ban amount to growing lawlessness and why courts must now step in.

The CJEU indeed did step in. In Commission v. Poland, the Court ruled that Poland’s Constitutional Tribunal is not a lawful court. Yet the rule of law crisis in Poland is far from over. JAKUB JARACZEWSKI and LAURENT PECH (ENG) unpack what the judgment means and why implementing it will be difficult. WOJCIECH SADURSKI (ENG) further considers its significance and what the Polish government might do next.

The CJEU also pushed Poland to act on another front. In Trojan, the Court held that EU Member States must recognise a same-sex marriage lawfully concluded in another Member State. ALIX SCHULZ (ENG) highlights how the Court seeks to ensure that EU citizens fully benefit from the legal effects arising from that status. MATTI WARNEZ (ENG) builds on this by explaining how Trojan mobilizes national judges to recognize same-sex marriages and pushes Poland towards adopting civil partnership legislation.

The Court further strengthened anti-discrimination in the Danish “ghetto” case, raising broader questions about how housing fits into EU anti-discrimination analysis. SERDE ATALAY (ENG) reflects on the co-constitutive nature of stigma and dispossession.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

HUMANISTISCH. NACHHALTIG. HANDLUNGSORIENTIERT.

Die Leuphana Universität Lüneburg steht für Innovation in Bildung und Wissenschaft. Methodische Vielfalt, interdisziplinäre Zusammenarbeit, transdisziplinäre Kooperationen mit der Praxis und eine insgesamt dynamische Entwicklung prägen ihr Forschungsprofil in den Themen Bildung, Kultur, Management & Technologie, Nachhaltigkeit sowie Staat. Ihr Studienmodell mit dem Leuphana College, der Leuphana Graduate School und der Leuphana Professional School ist vielfach ausgezeichnet.

An der Leuphana Universität Lüneburg ist folgende Professur zu besetzen:

– ÖFFENTLICHES RECHT MIT INTERNATIONALEN BEZÜGEN (W2/W3)

NEUGIERIG GEWORDEN? Die vollständige Stellenausschreibung finden Sie hier.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

And there’s more from Luxembourg. In its judgments in W.S. et al and Hamoudi, the Court made clear that Frontex cannot evade judicial responsibility for fundamental rights violations. Taken together, the cases push back against Frontex’s long-standing structural irresponsibility and reaffirm the rule of law in EU asylum governance, as CATHARINA ZIEBRITZKI (ENG) observes.

As we’ve already analysed last year (still fresh in our minds, as if it were two weeks ago), the ECJ’s Russmedia ruling quietly overturns a cornerstone of EU platform law. ERIK TUCHTFELD (ENG) shows how GDPR liability may replace notice-and-takedown with de facto monitoring – potentially reshaping online speech across Europe. The judgment clearly shook EU intermediary liability law, though its full extent remains unclear. MICHAEL FITZGERALD (ENG) offers three possible readings of the case.

Russmedia demonstrates once more how complex EU digital law has become, fuelling calls for simplification. As HERWIG C.H. HOFMANN (ENG) writes, recent proposals like the draft Digital Omnibus regulation are strong on restricting rights but light on providing clarity. He explains why the Digital Omnibus risks deepening legal uncertainty and what genuine simplification of the EU’s digital acquis would require.

The other Omnibus also promised simplification, this time for key EU corporate sustainability instruments. But what did it actually deliver? INÉS RACIONERO GÓMEZ (ENG) argues that the Omnibus I doesn’t simplify the CSDDD – it quietly dismantles it while preserving the regulatory façade.

Another quiet EU development came from its Council. By adopting Regulation 2025/2600, it effectively froze Russian state assets permanently. TIL LEICHSENRING and JULIA POPP (ENG) contend that this permanent freezing remains primarily designed to address matters of foreign policy and violates the principle of conferral, and outline its potential long-term effects.

EU security policy seems increasingly urgent. The US’ recent adoption of its National Security Strategy suggests that the European Union may need to make swift, existential decisions in the coming years to better protect its interests. SAMUEL SHANNON (ENG) suggests that Europe look to US history for guidance on how to proceed and create what he calls “a 1787 moment.”

Since waiting for such a moment (and a coherent EU security policy) might take too long, Member States are turning to national approaches. Germany has been debating compulsory military service for months. As of 1 January 2026, Germany will introduce a “new military service”: participation will initially be voluntary, but all 18-year-old men must undergo military assessment, while women may opt in voluntarily. Is that fair? SVEN ALTENBURGER (GER) argues that equal burden-distribution would only be possible through a general, gender-neutral compulsory service.

When Parliament curtails constitutional rights, it must always identify the specific right at issue and the constitutional provision it appears in. This citation requirement under Article 19(1) is rarely discussed, yet the Court’s case law has steadily eroded it – most recently in Martinstor. JOHANNES SCHÄFFER (GER) calls for a straightforward choice: either restore the requirement as a meaningful safeguard or scrap it entirely.

Not only Parliament but also the courts must give reasons. In Gondert v. Germany, the ECtHR strengthened the duty to give reasons and thereby protected the “dialogue between courts” in the triangular relationship between EU law, the ECHR, and national legal orders. PETER HILPOLD (ENG) explains how the ECtHR achieved this and where judicial dialogue still falls short.

The ECtHR is also struggling with its own internal dialogue – it has come under pressure from its member states. Given the ongoing interference with the Court, MARGARITA S. LLIEVA (ENG) proposes that it should define and apply contempt measures to sanction member states intruding on its independence and impartiality.

Another European human rights instrument faces mounting pressure: the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence. In October 2025, Latvia attempted to withdraw from the Istanbul Convention. KALVIS ENGIZERS (ENG) uses this episode to show how disinformation and patriarchal myths undermine democracy.

Meanwhile, Latvia’s neighbour Belarus weaponizes Interpol Red Notices to hunt exiled activists across Europe, as filmmaker Andrei Hnyot’s year-long detention on fabricated tax charges illustrates. For BEN KEITH and JACQUELINE JAHNEL (ENG), this creates a procedural paradox for the EU: mutual-trust systems like Schengen must filter politicized data to uphold ECHR Article 3 and Charter Article 19 non-refoulement duties. Can Europe’s constitutional safeguards withstand this authoritarian assault on cooperative policing?

New forms of cooperative policing are emerging – now in partnership with AI. As police across Europe rapidly expand their use of AI – from Palantir in Germany to AI-supported surveillance in France and Luxembourg – the regulatory landscape remains fragmented. MARIUS KÜHNE and ANDREAS KANAKAKIS (ENG) map both the dangers and the way forward.

Germany offers a striking example of such fragmentation: Saxony is planning a new Police Act that makes intelligent data analysis, AI-assisted video surveillance, and biometric matching central tools of preventive policing — with implications far beyond the federal state. For EYK LENSCHOW (GER), this raises the question of how much tech-driven efficiency a liberal constitutional order can tolerate before crossing its own red lines.

Berlin is following suit: a new law turns crime hotspots into hubs of automated video surveillance and AI-powered behavioural analysis — a major breach of the right to informational self-determination. PETRA SUSSNER (GER) criticises that despite assurances against racial profiling and discriminatory algorithms, the regulatory framework stays vague, proof of effectiveness is lacking, and entrenched stereotypes risk hardening rather than fading.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

PhD position in the Cluster of Excellence “Future Forests” at the University of Freiburg – Social-ecological systems research and sustainability law – Adaptation of forests to climate change

How can the role of law be made more visible in concepts of social-ecological systems research? What added value does social-ecological systems thinking offer in legal research? We are filling a doctoral position (75%, 3.5 years) in our international and interdisciplinary team, starting April 1, 2026. You will examine the role of law in social-ecological systems science and, based on concrete case studies, develop legal building blocks for adaptation and transformation pathways toward future-proof forests. The application deadline is January 31, 2026.

Find further information and apply here until January 31, 2026.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the U.S., universities are increasingly taking on policing functions, extending law enforcement into campus life. Columbia University provides a prime example. Five UN Special Rapporteurs recently addressed a letter to the university, raising concerns about protest policing, disciplinary sanctions, surveillance, and the treatment of non-citizen students and scholars tied to Gaza-related speech and assembly. When UN Special Rapporteurs send an allegation letter to a university, international law is doing something unusual. SAFIA SOUTHEY (ENG) sees this as a first step toward closing the accountability gap for formally private but functionally governmental institutions.

Many legal conflicts play out on this hazy public-private divide: Last month, an exhibition by Cypriot artist Gavriel was cancelled after political outrage, death threats, and a violent attack. The episode poses a core question under Article 10 ECHR: does quashing artistic expression through political pressure and institutional pullback count as an interference with freedom of expression, even without a formal ban? NATALIE ALKIVIADOU (ENG) shows how Art. 10 ECHR fails when artistic freedom hinges on prevailing religious sensibilities.

Speaking of religious sensibilities: The Federal Ministry of the Interior now aims to tackle not just “violent Islamism” but also so-called “legalistic Islamism”. With this conceptual expansion, NAHED SAMOUR (GER) argues this shift drags the Ministry into legally fraught terrain, where security assessments could override constitutional rights and access to justice.

Another term challenges German legal practitioners. As antisemitic incidents in Germany have risen sharply since October 7, 2023, intensifying pressure on courts, public authorities, employers, and universities to determine where democratic contestation ends and unlawful discrimination begins. These decisions demand binary ruling – lawful or not, permissible or sanctionable – even when social meaning, political symbolism, and intent remain deeply contested, as REUT YAEL PAZ (ENG) writes.

Faced with similar questions, an Austrian court recently sentenced the former editor-in-chief of the far-right magazine Aula to four years in prison for “re-engagement in the Nazi sense” and Holocaust trivialisation. For ULRICH WAGRANDL (GER), the case demonstrates that Austrian liberal democracy can also show a defensive, protective side: despite historical gaps, the country’s democracy is capable of defending itself.

But is self-defence really the best strategy for democracy? BOJAN BUGARIC (ENG) contends that democracy is best protected not by banning its opponents, but by rebuilding popular support through participation, persuasion, and substantive reform.

Bolsonaro is testing that idea: After Brazil’s Supreme Court convicted him over the January 2023 coup attempt, many hailed this as a victory for the rule of law. But the new Dosimetry Bill, sharply reducing sentences, now casts those claims into doubt, as EVANDRO PROENCA SÜSSEKIND (ENG) observes.

Finally, the ICJ kicks off hearings in The Gambia v Myanmar. Over the course of three weeks, it will hear arguments on The Gambia’s claim that Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya breached Myanmar’s obligations under the 1948 Genocide Convention. MICHAEL A. BECKER (ENG) previews the key issues.

And with the end of the year, we’ve also wrapped up two debates.

In “In Good Faith: Freedom of Religion under Article 10 of the EU Charter”, we asked what protecting minorities requires. MARIA FRANCESCA CAVALCANTI (EN) argues that constitutional frameworks of religious freedom and non-discrimination prove insufficient to protect minority groups. PAUL BLOKKER (EN) highlights how reproductive rights in Europe are increasingly contested – not only in courts, but across parliaments and public arenas. KRISTIN HENRARD (EN) argues that the Court’s broader margin of appreciation in matters of freedom of religion encourages a national sovereignty creep. Looking at self-determination of the Church in the FCC’s Egenberger decision, LUCY VICKERS (EN) doubts whether group rights should be protected in the absence of individual members supporting the views of the church leadership. MATTHIAS MAHLMANN (EN) shows why the FCC’s shift towards equality and non-discrimination in Egenberger constitutes a well-justified, fundamental-rights-friendly, and welcome departure from a decades-long practice. MATTHIAS WENDEL and SARAH GEIGER (EN) close the debate by explaining how Egenberger brought back the old Solange test, which could potentially justify an exception to the primacy of EU law.

For our symposium “Who Owns Science”, JULIA WILDGANS and TOBIAS HEYCKE (GER) explore creativity in science: Can research data enjoy copyright protection? Who “owns” a scientific publication? And who decides if, when, and how research findings are published? TRISTAN RADTKE (EN) analyses the scope and revocability of rights granted to publishers. Researchers, publishers, libraries, and research funders are the key players in the world of scientific publishing – and each holds leeway to strengthen Diamond OA. JOSEPHINE HARTWIG (DE) maps out these spaces and their limits. ELENA DI ROSA (EN) asks what it needs to transform the publishing system – for real, this time.

Rather than a happy new year, may you steer through it deftly. Don’t forget to dream, don’t forget Lviv.

*

That’s it for this week. Take care and all the best!

Yours,

the Verfassungsblog Team

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an e-mail, you can subscribe here.