Protecting Democracy in the Digital Era

What Can Competition Law Contribute?

At the dawn of 2025, liberal democracy is faced with a considerable challenge: Big Tech bosses appear to leverage their market power for far-reaching political influence, without any democratic legitimisation to do so. As someone working on issues of market power in the digital economy, one cannot help but wonder: shouldn’t competition law be able to contain (some of) this unseeming wielding of market power? This has been a core question in my research in recent years (see here, here, here and here), and that question has never seemed as relevant as today. Before delving into competition law’s possible contribution to tackling the anti-democratic wielding of Big Tech market power, a caveat is in order: competition law can certainly contribute to protecting democracy in the digital era, but it can only do so in addition to more targeted laws and regulations.

A little background

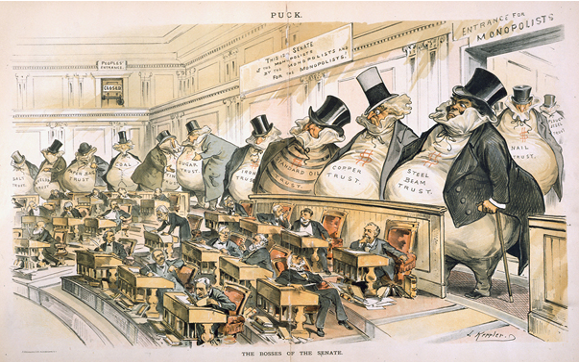

Let’s rewind to the outgoing 19th century for a moment. Back then, lawmakers in the US were faced with a similar question, as the big trusts were using their economic power for political gain. Joseph Keppler famously captured the sentiment of that era in his cartoon ‘The Bosses of the Senate’, published in Puck in 1889.

At the same time, Senator John Sherman cautioned: “If we would not submit to an emperor we should not submit to an autocrat of trade with power to prevent competition and to fix the price of any commodity.” Ultimately, this led to the adoption of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 and marked the beginning of competition law in the US.

Over the years, US competition law has often come to focus on a narrow understanding of consumer welfare, dressed in considerations of efficiency. In the face of the challenges that Big Tech appears to be increasingly posing to liberal democracy, some may find that it is time to reconsider antitrust’s original role: that of curbing the undue power of economic players.

In the European Union, which introduced competition law in the 1950s under quite different circumstances, the goals of competition law have remained more diverse, not least because of the market integration imperative. The European competition law provisions are contained in one of the Founding Treaties (dare I say: in the European constitution, on the Verfassungsblog?). They stand side-by-side with value assertions pertaining to our European democracy (in particular, Article 2 TEU) and the rights enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which can have a bearing on their interpretation and application. Only recently, in Google Android, the EU General Court made clear what can be at stake in digital competition cases. It found that Google’s abusive conduct was harming users’ interests in accessing multiple sources of information online. These interests, the Court reminded us, were ‘not only consistent with competition on the merits, [but] also necessary in order to ensure plurality in a democratic society’.

Addressing democracy-related concerns through competition law

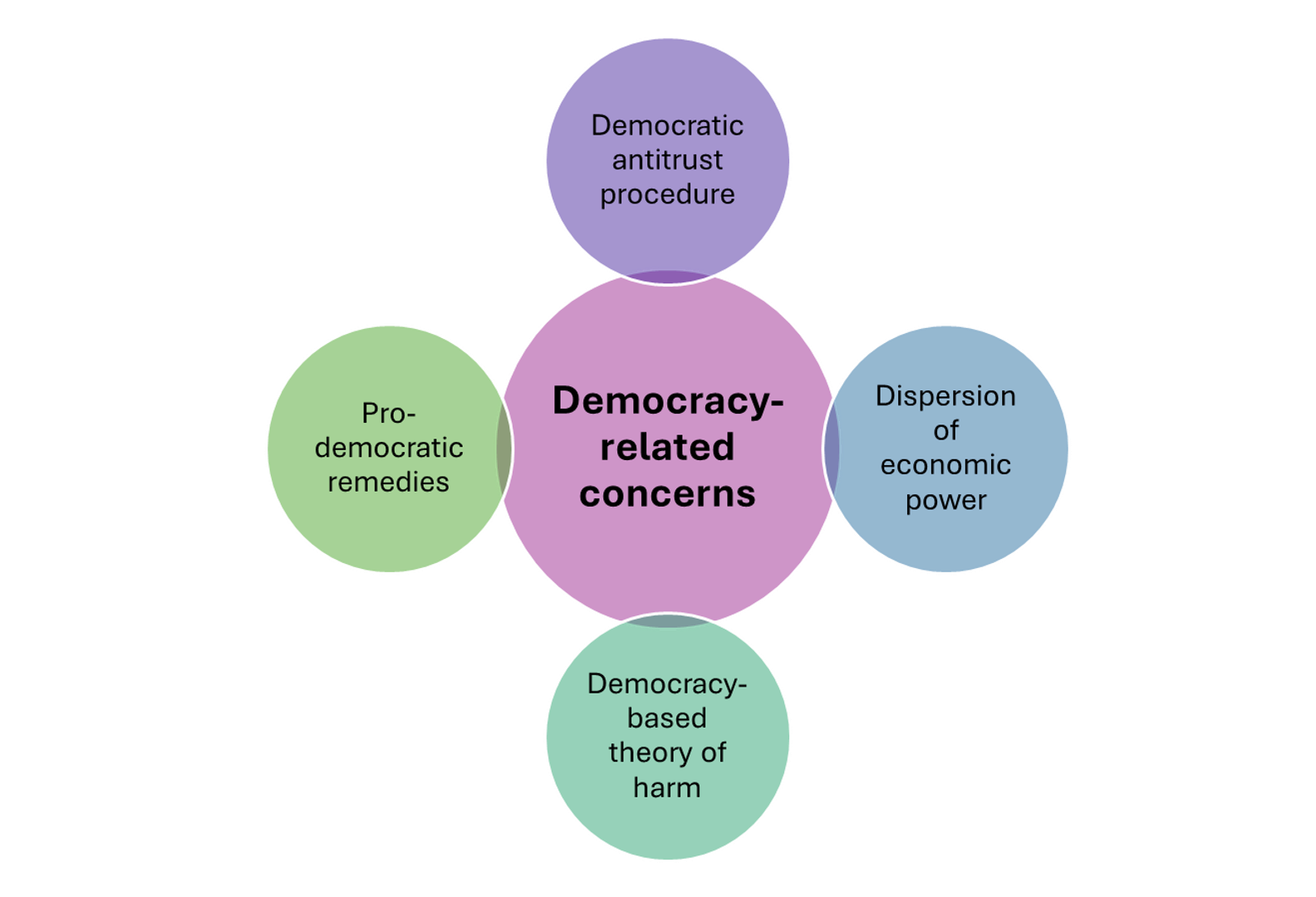

Against this background, the question looms as to how today’s competition law could respond to democracy-related concerns that stem from Big Tech companies and their leaders. We can discern a metalevel approach and a more targeted approach.

On a metalevel approach, competition law can ensure that antitrust procedure is strongly rooted in democratic principles. This includes due process, a regard for fundamental rights, and the independence of competition authorities. Importantly, it also includes ensuring that competition authorities, when interacting with stakeholders and experts, are given full disclosures of possible capture – a game that Big Tech has been playing very effectively. By focusing on democratic antitrust procedure, the institutions enforcing competition law are strengthened, which will eventually benefit the cases they are handling.

Competition law’s response to democracy-related concerns; based on Robertson, Antitrust Bulletin 2022.

Still on a metalevel, but perhaps more to the point, competition law can re-focus on one of its core missions: the dispersion of economic power. Much of the current debate on Big Tech circles around issues of overwhelming market power that is concentrated in the hands of a few persons that are in no way democratically accountable. Curtailing economic power can therefore be effective to get to the root of the problem. Merger control has an important role to play here. Multiple digital mergers that were given the green light in the past have contributed to the current concentration of market power, meaning that a more cautious approach may be in order going forward. Rules on unilateral conduct could also be a useful tool, as they police the exercise of market power. Their effectiveness depends on the theories of harm that are applied, which brings us to a more targeted approach:

Theories of harm that specifically take democracy-related concerns into account, be it in merger control or in unilateral conduct, may allow competition authorities to more closely consider instances in which powerful companies enter the political terrain without any democratic legitimisation. Media pluralism as a criterion is already considered by multiple competition authorities when assessing mergers, including in Austria. Another possible avenue was shown in the European Court of Justice’s Meta v Bundeskartellamt case of July 2023: in that case, the Court agreed that an external benchmark – in the case at hand: an infringement of the General Data Protection Regulation – could be informative when a competition authority assesses whether a dominant company was acting in line with competition on the merits. Why not use benchmarks that specifically serve to protect (digital) democracy as well? Possible candidates include the Digital Services Act, the Targeted Political Advertising Regulation, the European Media Freedom Act, amongst others. While some might argue that it contradicts competition law’s true goals when competition theories of harm are infused with democratic values, others might see this as a return to the historic roots of antitrust law. Either way, this approach requires a more detailed analysis to ensure its workability.

A further possibility for competition law is to ensure that antitrust remedies – be it in mergers or in conduct cases – are pro-democratic. This criterion could be taken into account whenever a digital case involves a remedy and there is a choice to be made between different types of remedies.

Conclusions

As competition authorities are grappling with their possible role in supporting the protection of democracy in the digital era, the four approaches outlined above may show ways in which this is feasible and in line with the current legal framework. To conclude, three issues stand out:

First of all, democracy is multi-faceted. In order to consider the type of response competition law should resort to in more practical terms, it is useful to think of particular democratic values, including a free vote, free debate, media pluralism, etc. Then, one can consider how value chains in digital markets and the way in which competition operates in these markets relate to these values, particularly as regards network effects, targeted advertising, click-bait, etc. In doing so, competition authorities may see how individual aspects of democracy can easily fit into a competition law analysis.

Second, competition authorities must pursue cases in which democracy is at stake. In December 2024, a Roundtable at the OECD discussed the interface between democracy and competition law. One delegation highlighted the importance of case selection and prioritisation in this respect, and I couldn’t agree more: competition authorities need to take on the hard cases in which different aspects of liberal democracy are being hampered by market participants. They should not shy away from these cases. Recent reports in the Financial Times suggest that the European Commission may be bowing to the political pressure from overseas and rethinking the enforcement of its digital regulation – including competition law, the Digital Markets Act and the Digital Services Act. If this were true, it would not bode well for our European democracy and for the digital regulation that is protecting our European values. It would not bode well at all.

Third, competition law can only act as a complement. More targeted laws and regulations are urgently needed – and where they exist, they need to be vigorously enforced.

FOCUS is a project which aims to raise public awareness of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, its value, and the capacity of key stakeholders for its broader application. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.