Recognizing Court-Packing

Perception and Reality in the Case of the Turkish Constitutional Court

There is near scholarly consensus that President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has successfully packed the Turkish Constitutional Court (TCC). Court-packing in the commonly understood sense of expanding the membership of the court, appointing judges with long tenures that extend beyond a couple of election cycles, and who are ideologically committed to the executive’s constitutional vision, however, is still foreign to Turkey’s political elites.

The constitutional amendments introduced in 2017 set the number of TCC judges at 15 and abolished military high courts, ending the practice of selecting judges among military judges. Currently, the TCC has 16 members – a temporary anomaly: the position of the one military judge, currently on the Court, Serdar Ozguldur, will not be filled when he retires, which is imminent. Apart from Ozguldur, who was appointed by Ahmet Necdet Sezer, President Gul’s predecessor, all members currently serving on the TCC have been appointed either under Gul or Erdogan’s presidency.

The scholarly position that the Court has been packed rests on these facts that no one disputes: Erdogan has already made 5 appointments to the Court since he became president in 2014, 2 of which were enabled by the vacancies created after the dismissal of two Gul appointees from the Court for their alleged involvement in the 2016 coup attempt (Alparslan Altan and Erdal Tercan). 1 member was appointed by Parliament in 2015, under Erdogan’s effective control. The next presidential and parliamentary elections, assuming that there will be no early elections, will be held in 2023. Between 2019 and 2023, 5 additional members of the Court are expected to retire, and all 4 remaining vacancies will be filled by incumbent political elites: 2 directly by Erdogan, and 2 by Parliament under Erdogan’s control, due to his party’s de facto coalition with the right-wing Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetci Hareket Partisi). In sum, by 2023, Erdogan will have directly appointed 7 members to the Court and supervised 3 Parliament-made appointments. That adds up to 10 members of the 15-member Court. If and when the opposition reshuffles Turkish politics in the 2023 parliamentary and presidential elections, they will be confronted with a Court whose members have been directly or indirectly appointed by their chief political rival President (or perhaps former President) Erdogan to a large extent.

Given these existing and anticipated numbers, how does the situation not amount to court-packing?

Short Judicial Tenures

As of 2019, excluding the judges currently serving on the Court (16 and soon to become 15), I have compiled and evaluated publicly available data on all former 115 Constitutional Court judges who served on the Court since its founding in 1962. Most of the data on 113 of the judges come directly from the Constitutional Court’s official website containing basic biographical information on all but 2 former judges.

The results indicate that the average tenure was around 2607 days or about 7 years.

A judge serving an average of 7 years cannot hope to accomplish much. The 7-year average is undesirable from a technocratic point of view, as it is simply not long enough for a judge foreign to constitutional law to develop the requisite expertise. Second, the 7-year average falls short of covering even two election cycles. Under Article 77(1) of the current Turkish Constitution, with the 2017 amendments, parliamentary and presidential elections are held every 5 years. One reason for granting constitutional court judges relatively long tenures – though not necessarily life tenure – is that they extend beyond several election cycles and thus effectively insulate judges from ordinary politics. The 7-year average defeats that purpose.

The 1961 and 1982 Constitutions stated that constitutional court judges were to serve on the Court until they had reached the age of 65. In 2010 a further limitation was imposed. Judges appointed after this amendment took effect are to serve for a non-renewable term of 12 years. This means that starting with appointments made in 2010, members of the TCC must retire either after 12 years from the time of their appointment or when they turn 65, whichever is earlier. Members appointed before the 2010 amendments, however, are only bound by the mandatory retirement age.

The following example shows how consequential this combination of limitations can be for the Court: The current president of the TCC, Prof. Dr. Zuhtu Arslan, a constitutional law scholar who almost always sides with the court’s liberal wing, was appointed to the Court in 2012 by former President Gul. Since Arslan was appointed 2 years after the 2010 amendments had gone into effect, he is expected to retire either when he attains the age of 65 or when he has served on the Court for 12 years, whichever is earlier. Born in 1964, he would have been able to serve until the age of 65 under the pre-2010 tenure rules, i.e. until 2029. But since the 12-year term rule applies, he must retire in 2024, five years earlier than would have been the case otherwise. Compare his case to that of Prof. Dr. Engin Yildirim. He was also appointed by Gul and is undoubtedly the most liberal member of the Court. Yildirim was appointed in 2010, right before the amendments went into effect. He is thus not bound by the 12-year term rule, but only by the mandatory retirement age of 65. Born in 1966, Yildirim is expected to retire in 2031.

Patronage Appointments

There is some, albeit inconclusive, evidence that some current members of the Court have had extensive relations with the governing political elites prior to their appointments. 3 out of 4 of President Erdogan’s most recent appointments to the Court are all overtly political appointments: Mr. Yildiz Seferinoglu and Mr. Selahaddin Mentes both previously held the explicitly political title of Deputy Justice Minister and Mr. Recai Akyel, served at the Court of Accounts while simultaneously being an aide to the president.

Similarly, Prof. Dr. Yusuf Sevki Hakyemez, appointed by Erdogan in 2016, was a member of the now-defunct “Wise People” – an AKP-organized group of intellectuals tasked with aiding the government’s former policy of resolving what was then termed “the Kurdish problem”.

All of these 4 post-coup attempt appointments are, to varying degrees, political. As such, the political nature of these appointments says nothing positive or negative about the appointees’ qualifications. And this is precisely the irony of patronage appointments that the opposition may take advantage of in the future: Erdogan chose these appointees because they were considered “safe” candidates. Safe in the sense that they are expected to avoid decisions that would impair the interests of the AKP, and in the sense that they are believed to lead social lives similar to those of the governing elite. But it is precisely because the constitutional vision of the appointee – if he has one, of course (and I say he because AKP’s past appointees to the Court have all been men) – does not factor into AKP’s nominee selection deliberations, “safe” candidates do not always produce “friendly” outcomes. Yusuf Şevki Hakyemez, for example, though appointed by Erdogan in 2016, consistently sides with the liberal half of the Court – unsurprisingly so, given his many contributions to Turkish constitutional law literature as a liberal constitutional law scholar prior to joining the Court. The other Erdogan appointees seem to align with executive policies in high profile decisions for now, but that is no guarantee that they will continue to do so if the governing party loses political support.

Had Erdogan appointed judges with sufficiently complex and established ideas about constitutional law and doctrine that favored his own vision of the Constitution, he might have been said to have packed the Court. But that is not the case. “Insufficient and unideological short-term political capture that is bound to disintegrate if and when Erdogan loses power” might be a more accurate way of describing the current situation of the Court.

Looking Ahead: Any Hope for the Opposition?

Still, the fact that Erdogan will have had a direct or indirect say in 10 out of the 15 appointments to the TCC by the end of 2023 shows that the opposition’s task in seeking to appoint judges with favorable judicial philosophies is daunting. Should he run for another term in 2023 and win (which would be constitutionally problematic under the 2-term limit for presidents, as I argued in a previous blogpost), the fate of the Court might be sealed.

Should the opposition win both the presidential and parliamentary elections in 2023, they will be able to make a total of 8 appointments to the Court, as 8 members of the current TCC will retire between 2023 and 2028 (2 of the 8 are expected to retire in August 2028; should the presidency be reclaimed by Erdogan-led forces before August 2028, the opposition forces between 2023-2028 can still make 6 appointments to the 15-member Court).

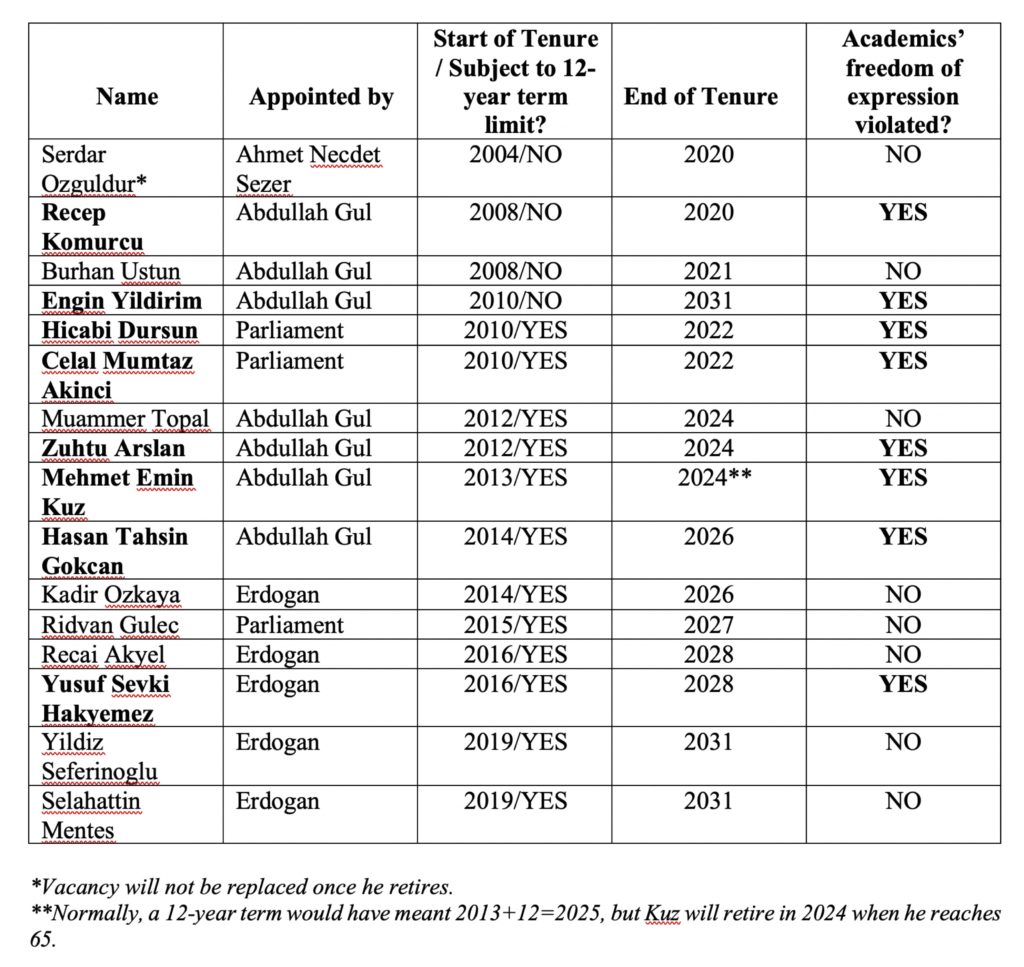

Below is a list of all current appointees, the president who appointed them, their tenure, and the year in which they are expected to retire. In an 8-8 decision, the Court recently ruled, that penalizing members of Turkish academia who signed the “Peace for Academics” declaration for spreading terrorist propaganda violated their constitutional rights of freedom of expression. Since there was a tie, which will not be possible after Ozguldur’s retirement, the vote cast by President Arslan became decisive, and he voted with the liberal wing. While one should be cautious as to generalizing about judicial behavior from this particular case, it may still serve as a good proxy for overall judicial inclination. Those who voted yes on the question of whether the “Peace Academics’” freedom of expression was violated can be assumed to constitute the liberal wing of the Court. The opposition should study this list as the 2023 elections draw near:

If an ambitious opposition secures a sufficient majority to amend the Constitution in 2023, which seems unlikely, it could abolish the 12-year term rule but preserve the mandatory retirement age of 65, and then appoint relatively young judges in their early 40s whose commitment to the opposition’s conception of constitutional law is firm and well-known. However, if and when the opposition replaces Erdogan, it will most likely be a coalition of political factions from the center right and left, making it difficult to appoint judges who espouse a particular judicial philosophy. Compromise will be unavoidable. But even then, appointing judges with a more liberal worldview might still be something the opposition can try to agree on.

Of course, the meta-question of whether court-packing per se is desirable, regardless of who engages in it, is a persisting question. Bracketing the question of whether it should try to do so, only time will tell if the Turkish opposition will be positioned to pack the TCC.

The author wishes to express his gratitude to Dr. Jane Fair Bestor for insightful comments and suggestions.

Ein sehr interessanter Artikel, der zeigt, dass die türkische Verfassungswirklichkeit wesentlich komplexer ist, als die intellektuellen Schnellschüsse in Politik und den Medien suggerieren.

Bedenkt man, dass gerade die zusätzliche Begrenzung der Amtszeit von Verfassungsrichtern von der AKP eingeführt worden ist und diese ein court-packing eher erschwert, stellt sich die Frage, wieso diese Partei, der ja gerade eine autokratische Tendenz unterstellt wird, eine solche Regelung bringt?

Zumindest zeigen die Abstimmungsergebnisse zu dem populären Fall des sog. “Friedensaufrufes”, dass selbst von Erdogan bestimmte Amtsträger, nicht automatisch auf Linie mit Erdogans Politik stehen. Zudem zeigen sie, dass auch nicht alle von Seiten der AKP eingesetzten Amtsträger Ansichten der Partei durchsetzen. Überdies zeigen sie, dass es auch innerhalb der Partei keine einheitlichen Ansichten gibt. Schließlich zeigen sie, dass diese Ansichten auch neben Erdogan bestanden/bestehen und politisch wirksam artikuliert wurden/werden. Medial wird häufig das Gegenteil suggeriert. Entsprechende Behauptungen finden sich mitunter auch im Kommentarbereich dieses Blogs (https://verfassungsblog.de/pluralismus-lehrstunde-fuer-die-tuerkei/).

Dem Artikel von Herrn Tecimer sind allerdings einige Informationen hinzuzufügen. Zum einen kann der Präsident nach den neuen Regelungen lediglich vier Sitze des Verfassungsgerichts frei bestimmen. Alle anderen Personen muss er aus Vorschlägen des Plenums des Kassationshofs, des Staatsrats und des Hochschulrats wählen. Selbiges gilt für das Parlament. Dieses kann nur aus Vorschlägen des Rechnungshofs und der Anwaltskammern wählen. Berücksichtigt man zudem, dass ein Mindestalter von 45 Jahren bestehen muss, wird deutlich, dass ein court-packing generell und insbesondere für Erdogan noch schwieriger ist. Der Großteil des zur Verfügung stehenden Personenkreis ist der alten kemalistischen Elite zuzurechnen und wird von dieser auch vorgeschlagen.

“ARTICLE 146- (As amended on April 16, 2017; Act No. 6771) The Constitutional

Court shall be composed of fifteen members.

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey shall elect, by secret ballot, two members from

among three candidates to be nominated by and from among the president and members of the

Court of Accounts, for each vacant position, and one member from among three candidates

nominated by the heads of the bar associations from among self-employed lawyers. In this

election to be held in the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, for each vacant position, two

thirds majority of the total number of members shall be required for the first ballot, and absolute

majority of total number of members shall be required for the second ballot. If an absolute

majority cannot be obtained in the second ballot, a third ballot shall be held between the two

candidates who have received the greatest number of votes in the second ballot; the member

who receives the greatest number of votes in the third ballot shall be elected.

(As amended on April 16, 2017; Act No. 6771) The President of the Republic shall

appoint three members from High Court of Appeals, two members from Council of State from

among three candidates to be nominated, for each vacant position, by their respective general

assemblies, from among their presidents and members; three members, at least two of whom

being law graduates, from among three candidates to be nominated for each vacant position by

the Council of Higher Education from among members of the teaching staff who are not

members of the Council, in the fields of law, economics and political sciences; four members

from among high level executives, self-employed lawyers, first category judges and public

prosecutors or rapporteurs of the Constitutional Court having served as rapporteur at least five

years.

(As amended on April 16, 2017; Act No. 6771) In the elections to be held in the

respective general assemblies of the High Court of Appeals, Council of State, the Court of

Accounts and the Council of Higher Education for nominating candidates for membership of

the Constitutional Court, three persons obtaining the greatest number of votes shall be

considered to be nominated for each vacant position. In the elections to be held for the three

candidates nominated by the heads of bar associations from among self-employed lawyers,

three persons obtaining the greatest number of votes shall be considered to be nominated.19 […]”