Using the Constitution for Partisan Benefits

On the Reservation of Women in the Indian Legislative Assemblies

Last month, the Indian parliament passed the 106th amendment to the Constitution. It inserted several provisions to the Indian Constitution, collectively providing for horizontal reservation of one-third of directly elected seats of the House of the People, the state legislative assemblies, and the Delhi legislative assembly for women. The reservation is to continue for fifteen years from the date it is enforced in respective assemblies, and its duration could be extended further by a law made by the parliament to this effect.

In this blog, I discuss the political motivations underlying the enactment of this amendment and argue that this amendment is an opportunistic attempt by the incumbent government to reap partisan benefits using the Constitution before the upcoming state and general elections. Such actions demystify the idea that constitutions are a place for high-order politics. The amendment shows that with enough numbers, constitutions could easily be reduced into a political tool for furthering dominant political interests. While constitutions may claim to entrench certain values and present themselves as the identity of the society, the true entrenchment of values demands their internalization by the majority, which should be active in calling out, through available avenues, the partisan or unconstitutional nature of governmental actions.

Reservation for Women: A Promise to Deliver in the Future

A quick reading of the 106th amendment would show that it seeks to create a scheme of reservation for women to nudge their increased participation in the Indian legislatures. It would seem to be a continuation of the efforts that began with the introduction of the 73rd and 74th amendments to the Constitution in 1992, which, for the first time, formally introduced the idea of reservation for women in the Indian constitutional imagination by reserving seats in the local representative bodies. However, once we read the amendment in light of the prevailing political situation in India, a different picture emerges.

The amendment introduces Article 334A to the Constitution, stipulating that the reservation of seats for women will not be immediate but will occur ‘after an exercise of delimitation is undertaken for this purpose after the relevant figures for the first census taken after commencement of the Constitution (One Hundred and Sixth Amendment) Act, 2023 have been published’. Since the late 19th century, India has regularly undertaken a census every ten years until 2021, when the COVID-19-induced lockdown delayed it. In July of this year, the government further delayed taking a decision on the conduct of the 2021 census exercise to 2024-25. The term of the current national government is set to expire in May 2024. It is, therefore, certain that seats for women will not be reserved in the upcoming general elections. Moreover, while there is no certainty that the census will take place in 2024-25, even if, hypothetically speaking, the government adheres to this timeline, it is nearly certain that the delimitation exercise will take around 4-5 years from the date of the conduct of the census. Therefore, it appears that India will have at least two national governments before the 106th amendment fulfills its promise.

It cannot be denied that if the government had honest intentions about women’s reservation, it could have introduced the reservation with immediate effect within the existing delimitation formula. So, why was the amendment introduced in the first place? In my opinion, the answer lies in the political capital that the Bharatiya Janata Party (‘BJP’) hopes to gain from this illusion of constitutional ‘change’.

Five Indian states are set to vote this November, followed by the 2024 general elections. While multiple opinion polls conducted to date position the BJP strongly in the 2024 elections, there is a genuine fear of a reduction in its win margin compared to the 2019 election. The 106th amendment, therefore, seems like a political strategy of the BJP to woo female voters and consolidate their votes before the elections. It forms part of a series of women-focused initiatives by the BJP that are making headlines, with the latest one being the mass mobilization of women and the distribution of free tickets for the cricket World Cup opener between England and New Zealand.

The other important political maneuvering that the BJP intends to undertake using the 106th amendment is to preempt the debate on the delimitation process in India. After India’s independence in 1947 and the conduct of three continuous delimitation exercises in 1952, 1963, and 1973, India’s delimitation formula has been frozen as a way to incentivize family planning. It was frozen in 1976 for 25 years, and then the 84th amendment froze it for another 25 years. As a result, the current delimitation is based on the 1971 census data, and the next delimitation exercise is set to be undertaken after ‘the relevant figures for the first census taken after the year 2026 have been published’ [Article 82], unless it is extended further.

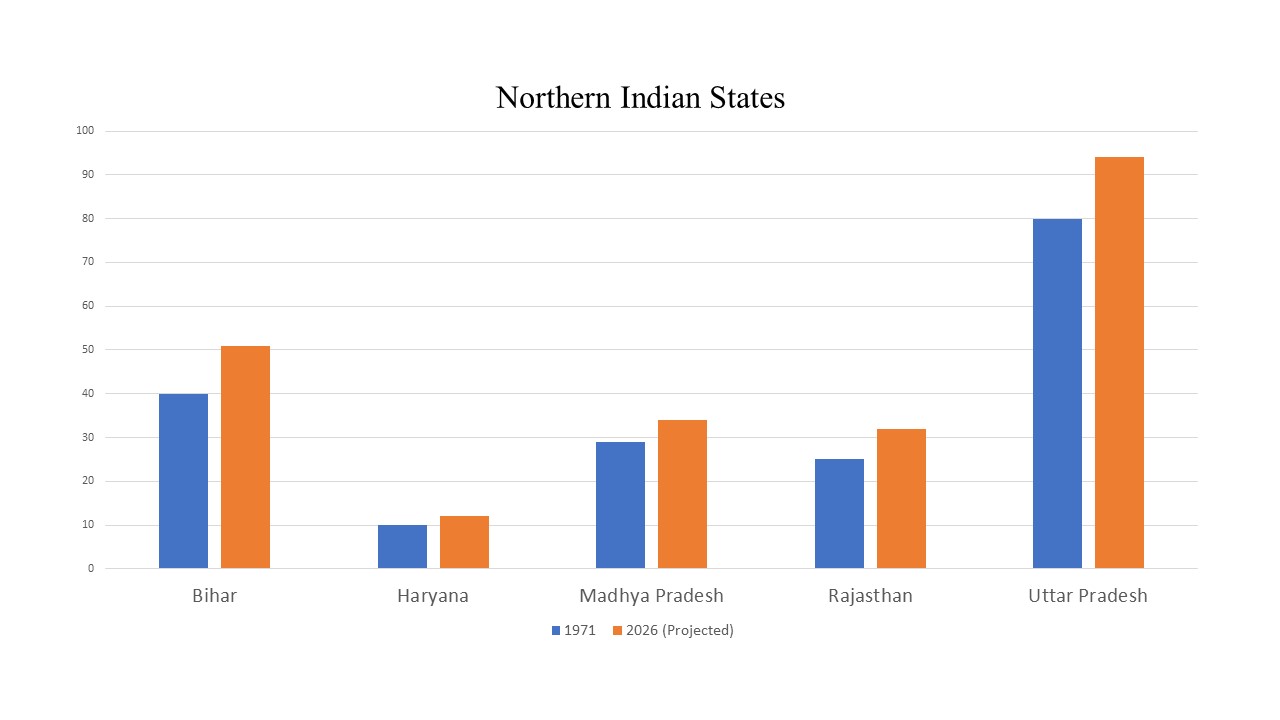

The considerable political opposition to a fresh delimitation in India stems from the disparate outcomes of family planning in India. While the southern states have been successful in managing their population growth, the northern states have shown dismal performance. Consequently, if delimitation is conducted based on the current population composition, the southern states are set to lose their parliamentary influence to their northern counterparts, and the loss would be quite significant. To quote an example, an estimate shows that if delimitation is conducted based on the projected 2026 Indian population, the southern state of Tamil Nadu would lose nine parliamentary seats and reduce its representation to 30 seats, whereas the northern state of Uttar Pradesh would gain 14 seats, increasing its seat share to a staggering 94. A similar story runs in other states of the two regions.

The graph below presents this north-south divide by using the examples of a few Indian states:

These graphs clearly tell the story of why the southern Indian states are resisting delimitation. By linking the idea of women’s reservation to delimitation, the incumbent BJP government is trying to shift the conversation about delimitation away from the question of family planning (and its possible negative consequences for the southern states) and link it to the question of women’s representation in the legislature. While it is easier and totally justifiable for political parties to flag family planning as a reason to oppose delimitation, the resistance becomes tricky and perhaps even inconvenient when it also hampers women’s increased participation in the legislative bodies.

These graphs clearly tell the story of why the southern Indian states are resisting delimitation. By linking the idea of women’s reservation to delimitation, the incumbent BJP government is trying to shift the conversation about delimitation away from the question of family planning (and its possible negative consequences for the southern states) and link it to the question of women’s representation in the legislature. While it is easier and totally justifiable for political parties to flag family planning as a reason to oppose delimitation, the resistance becomes tricky and perhaps even inconvenient when it also hampers women’s increased participation in the legislative bodies.

A natural question to ask at this stage is why the BJP is pushing for delimitation. The answer is simple – the BJP is predominantly a northern party. In both the 2014 and the 2019 general elections, most of the BJP members of parliament were elected from the northern states. For instance, out of the 303 seats that the BJP won in the 2019 election, it won 62 out of 80 in Uttar Pradesh, 24 out of 25 in Rajasthan, 10 out of 10 in Haryana, 17 out of 40 in Bihar (its coalition partner won another 16 seats), and 28 out of 29 in Madhya Pradesh. In contrast, the BJP’s performance in the southern states was abysmal – it won no seat in Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh, and 4 out of 17 in Telangana. The only southern state it performed well in was Karnataka, where it won 25 out of 28 seats. In this situation, delimitation based on the present population composition is certain to yield electoral benefits for the BJP.

Against this backdrop, the 106th amendment helps the BJP in pushing for the delimitation exercise by anchoring the conversation around it to women’s representation in legislative bodies. The BJP’s intent is further underscored by related developments, such as the construction of a new parliamentary building with increased seating capacity and the inclusion of a provision that ties the rotation of reserved seats to delimitation in the 106th amendment.

Article 334A(3) provides in this regard that the rotation of seats reserved for women ‘shall take effect after each subsequent exercise of delimitation as the Parliament may by law determine.’ As incumbent politicians may create pressure to reclaim their seats (as they may not want to permanently cede their seats in favor of women candidates), the 106th amendment ensures that this pressure is expressed in terms of the demand for regular delimitation exercises.

The seats reserved for women in local representative bodies follow a different design. Rotation, at the local level, takes place every election cycle, which ensures that every constituency sends a women candidate at least every third electoral cycle. This rotation is not linked to delimitation. The linkage in the 106th amendment, therefore, is a conscious scheme change adopted by the BJP government to institute the practice of regular decennial delimitation exercise.

Due Process of Lawmaking

Another factor that shows how the current BJP government has reduced the constitution to a tool for everyday politics is the way the 106th amendment was introduced and passed in the parliament. The amendment bill was introduced in a surprise special parliamentary session, and it became the first bill to be moved in the new parliament building. Utmost secrecy was kept about the existence of the bill, and public engagement began only with its introduction in the parliament. It was passed the next day after its introduction in the lower house, and the upper house passed it the day after. The constitution was amended in three days, with no pre-legislative consultation, presentation of policy or draft bill, public participation, or civil society engagement. However, such questionable processes are emblematic of lawmaking in India. Lawmaking is largely a close-door party or government-driven swift exercise in India. The only avenue for debate and deliberation is the legislative bodies, which are also rendered powerless if the government controls a brute parliamentary majority.

The public discourse after the introduction and enactment of women’s reservation in the 106th amendment largely revolved around the issues of women’s empowerment, the political nature of the amendment, and caste politics. The aspects of due process of lawmaking were rarely discussed. It is high time that we acknowledge that many conversations need to be had about the need to institutionalize the due process of lawmaking in India.

Concluding Remarks

The 106th amendment to the Indian Constitution needs to be studied in its surrounding political context. While it does promise reservation of seats for women in the Indian legislatures in the future, its underlying intent is rooted in the possibility of electoral gains for the BJP. It is not a genuine step in the direction of women’s empowerment. Such partisan use of the Constitution must be highlighted and reflected deeply, particularly by the Indian society.

Dear Sir

what is total number of articles in the Indian constitution at present, 2024