When Judges Fall Silent

Why Neutrality is a Goal, Not a Given

“Before we go any further, you’ll have to tell us what actually happened at your demonstration,” my colleague instructs the claimant. “You know, that’s not something we’re familiar with. We judges aren’t allowed to demonstrate.”

“What on earth…?” I think, recalling all the demonstrations I’ve attended, without ever giving it much thought. Where does she even get that from? Once again, this must be the duty of neutrality.

Neutrality is the buzzword of our time. It dominates debates about state funding for Omas gegen Rechts – a civic group of “grannies” opposing the far right –, about rainbow flags in members’ offices of the Bundestag, Germany’s federal parliament, or judges who wear a headscarf. The desire for a neutral state – and neutral judges in particular – is entirely understandable and perfectly legitimate. The principle of neutrality is meant to prevent bias and partiality and thus ensure equal treatment for all. And yet, according to a recent ARAG survey, by 2025 only just over half of respondents in Germany still believed that courts treat everyone equally. So, what is going wrong? Why does the neutrality requirement fail to deliver on its own promise?

One reason may be that neutrality is an astonishingly vague concept. Neither the German Basic Law nor the Courts Constitution Act defines it. The judicial statutes of the federal states, such as section 31a of the Lower Saxony Judiciary Act, confine themselves to the (questionable) ban on wearing, while on duty, “visible symbols or items of clothing that express a religious, ideological, or political conviction” (better known as the “headscarf ban”). For a profession that otherwise insists on precise definitions, neutrality is presented to us as a professional – and even personal – expectation with remarkably little explanation, assuming that its meaning is self-evident.

It is precisely this vagueness that makes the concept of neutrality dangerous. It enables political extremists to instrumentalize neutrality for their own ends while portraying themselves as guardians of the rule of law. And although the duty of neutrality is meant to restrain state power, it often has the opposite effect: it makes it easier for those already in positions of authority to secure their power. Its indeterminacy spares them the effort of engaging seriously with the concerns or convictions of those accused of lacking neutrality. In fact, the mere existence of convictions is most of the time enough to call a person’s integrity into question.

Neutrality is for those who conform

In public discourse, neutrality is rarely defined in positive terms. Instead, it is defined negatively – by identifying what supposedly is not neutral. Apparently, any strong commitment to a particular cause or group quickly comes to be seen as incompatible with neutrality. What is striking – not just to me – is that accusations of non-neutrality tend to arise precisely when the cause in question is marginal, or the group affected is marginalized. In other words: when it concerns interests that do not preoccupy the societal majority.

This framing implicitly treats neutrality as the default condition and marks those who advocate for so-called “special interests” as outside the norm. But are people who take no interest whatsoever in the concerns of minorities or in unpopular issues truly neutral? Everyone pursues interests – some are progressive and transformative; others are conservative and preservationist. Wanting to maintain existing structures and resist change is no more neutral than wanting to reform them. It is a clearly articulated position that benefits certain groups and disadvantages others.

At the same time, accusations of non-neutrality also arise only when someone becomes visible, takes action, and raises their voice. This, too, implies that passivity is the preferred norm. Yet silence communicates a message just as clearly: that one approves of what is happening, or at least does not object strongly enough to risk provoking disagreement. Silence is not neutral. It is political. Neutrality must not be confused with indifference or looking away. Defined in this way, neutrality becomes an effective tool for enforcing conformity and suppressing inconvenient or disruptive voices.

Neutrality as a task

If neutrality does not mean passivity, and if it is not a natural default state, then what is it? Neutrality is neither a condition nor a character trait. It is a task.

As judges, we decide who is right and who is wrong, and the law grants us considerable discretion in doing so. But judgment cannot operate without values. Every judgment we pass on others also reveals something about ourselves, probably more than we would like. We measure others against our own expectations and project our assumptions onto them. Those assumptions are not necessarily accurate or fair. We try to be fair. We do not want to privilege or disadvantage anyone. We aim to balance competing interests justly. But how can we succeed in a society where some interests are far more deeply entrenched than others? Where there are interests we do not even perceive because we move within our own social bubbles?

We are generally well acquainted with the interests of the majority, of business, and of government policy, because we encounter them constantly. They do not need to be fought for; they assert themselves almost automatically. Assumptions such as the need for economic growth, the notion that work must pay, or the imperative of border control are so omnipresent that we barely recognize them as interests at all. They appear as necessities, almost as laws of nature. By contrast, the interests of minorities, marginalized groups, animals, or the environment are not omnipresent. They lack powerful lobbies. They are quieter and easier to overlook, especially for judges, who themselves only rarely belong to marginalized groups, whether through queer identities, migration histories, or working-class backgrounds.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Are you an early- or mid-career scholar or practitioner passionate about Democracy and the Rule of Law in Europe? Apply now for the re:constitution Fellowship 2026/2027!

If you need time and space to think and reflect on new projects and connect with other experts and institutions – our Fellowships provide just that!

We’re offering 15 Fellowships in two tracks from October 2026 to July 2027. Don’t miss out – the application deadline is 5 March at 12 noon (CET).

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Unconscious bias

Neutrality becomes possible only if we acknowledge that while we may be born neutral, we are quickly shaped by our families, social environments, schools, media, and politics into something that is anything but. This shaping is not our fault, and it is usually not even conscious. Nor is it inherently good or bad. But it carries with it stereotypes, gender roles, and discrimination in all its forms – racism, sexism, classism, violence against queer people, antisemitism, ableism, anti-Romani sentiment, social Darwinism, and more. Some of these forms of discrimination are so powerful that we internalize them, turn them against ourselves, and allow them to define who we are.

Nonetheless, there remains a widespread belief that discriminatory thinking and behavior always require malicious intent. In reality, discrimination often arises simply because we fail to reflect on our own privileges, beliefs, and bodies of knowledge, instead of treating them as self-evident. This is what is commonly referred to as “unconscious bias”. But because confronting our own prejudices and projections sounds exhausting – and because it may require admitting that we have made mistakes and wronged others – we prefer to reassure ourselves that good intentions are enough. From there, it is only a small step to denying the existence of structural or institutional racism altogether.

As long as we – judges included – do not seriously engage with our unconscious biases, challenge them, and work to unlearn them, we will never be neutral. Neutrality is a task: the effort to get as close as possible to reality. It means trying to perceive and understand not all, but at least as many different interests as possible at once. Neutrality does not simply happen. It requires active effort – not looking away, but looking closely; not remaining silent, but asking questions.

The status quo: normality instead of neutrality

Judges, however, operate under pressure. Who knows how long it will take before authoritarian populists come to power and turn their attention to the judiciary? We must not give them any ammunition. Out of fear of creating the appearance of non-neutrality, we choose not to act at all. We discipline ourselves and one another. We hammer down any nail that sticks out. Above all, we want to remain inconspicuous, to blend in. We hesitate to publish our decisions. We are reluctant to speak to the press – and when we do, we speak in a legal jargon that shuts people out. One anti-racism workshop every ten years seems sufficient, and the only conferences we attend are judges’ conferences, where we meet nothing but other judges who are just as well adjusted as we are.

We avoid demonstrations and political events. If we use social media at all, we do so anonymously. We wear no buttons and display no stickers on our laptops. Our hair is neither too short nor too long – and certainly not colorful. In our free time, we ride horses, train on racing bikes, or practice yoga. When something potentially political or polarizing occurs, we first wait to see which way the wind is blowing, so that we can later claim we always thought that way anyway. We do not speak publicly about our opinions or values – because, after all, what those are is supposedly obvious: normal.

Our image – the polished appearance of neutrality – matters more to us than neutrality itself. Only this explains our fixation on judges who wear headscarves, because you can see that they are not normal – sorry, neutral. You cannot see anything on us, and so nothing can happen to us. That this undermines transparency, that courts thus remain ivory towers and black boxes, is a price we are willing to pay. What matters most is that we do not fall from our pedestal, that people do not lose their reverence for us.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Das Justiz-Projekt: Verwundbarkeit und Resilienz der dritten Gewalt

Friedrich Zillessen, Anna-Mira Brandau & Lennart Laude (Hrsg.)

Wie verwundbar ist die unabhängige und unparteiische Justiz? Welche Hebel haben autoritäre Populisten, Einfluss zu nehmen, Abhängigkeiten zu erzeugen, Schwachstellen auszunutzen? Wir haben untersucht, welche Szenarien denkbar sind – und was sie für die Justiz bedeuten könnten.

Hier verfügbar in Print und digital – natürlich Open Access!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Trust instead of reverence

And yet, what the judiciary needs far more than reverence is trust. Our work cannot create legal peace if people do not trust us. That requires more than digitalization and faster proceedings. Trust grows when people feel seen and heard, when they are taken seriously. It erodes when they are ignored, dismissed, or treated with disdain. These experiences are particularly powerful when they happen to us personally, but they also shape trust when they happen to people close to us, or to members of communities with which we identify.

Justitia should not be blind. Wearing a blindfold is a luxury she can no longer afford at a time when democracy and the rule of law are eroding. She must be vigilant, sharpen her gaze, and keep her eyes everywhere. She must not overlook anyone – neither those who need her protection nor the forces that seek to instrumentalize and ultimately delegitimize her.

Towards a more open judiciary

Why do we not publish all our judgments? And not only on paywalled platforms like Juris or Beck-Online, but in a way that makes them freely accessible via a simple Google search? Yes, it would become apparent that we usually publish only the handful of decisions we consider particularly brilliant – because not all of them are. But hey, we are human.

Why do we not explain our judgments? Why are we so obsessed with the idea that judgments must “speak for themselves”? Judgments do not speak – no more than statutes do. A judgment that cannot be explained in a way that everyone can understand, even if they disagree with it, may simply not be a persuasive judgment.

Why do we not just let young probationary judges try things out? After seven or eight years of study and clerkship marked by micromanagement and intimidation, there comes a point when enough is enough. They will have unconventional ideas – and yes, we will say “we’ve never done it that way before.” And yes, it will be the first time.

Why do we not inform the public about upcoming hearings? It is somewhat absurd that we meticulously avoid changing courtrooms at short notice because someone might want to attend, while remaining entirely unbothered by the fact that no one ever attends, simply because no one knows what is happening.

Why is there such anxiety about courts on social media? Why the compulsion to always appear stiff and solemn? We are not legal machines. We can be competent and human at the same time – perhaps even witty.

Why do we not invite people into our courts? We could present the most interesting decisions of the month and give people the opportunity to respond. And we could simply listen and think about it.

Why are we not brave?

*

Editor’s Pick

by JASPER NEBEL

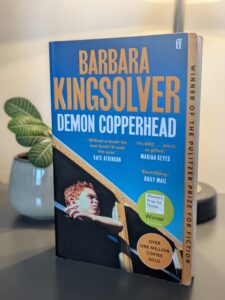

“First, I got myself born.” With the very first line of her novel “Demon Copperhead”, Barbara Kingsolver neatly illustrates that Damon (as the protagonist is actually named) faces much responsibility early in life – too much. The novel offers insights into the reasons behind Donald Trump’s rise and is thus a more enlightening alternative for those of us who, out of similar curiosity, might be drawn to J. D. Vance’s “Hillbilly Elegy” but do not want to read texts by authoritarians.

Kingsolver, with her vivid storytelling, makes Damon’s world feel immediately tangible to me: for years, he cares for his alcoholic mother, who repeatedly fails at rehabilitation, before navigating adolescence deeply shaped by exploitative foster parents and an overburdened social system. Kingsolver takes her time telling this life story without lecturing readers about the pitfalls of the “hillbilly way of life”. At first, she lulls us into a sense of security, until something enters Damon’s life that, at first sight, seems innocent – but will profoundly alter his life, as it has for so many Americans: OxyContin.

*

The Week on Verfassungsblog

summarised by EVA MARIA BREDLER

As CAROLIN DÖRR stated in the editorial with disarming clarity, neutrality is really about trust: state institutions and officials should behave in ways that make us trust them. And because trust is personal (for some, pink hair inspires confidence; for others, it triggers God-knows-what prejudices), we settle on a shared habitus that roughly corresponds to the grey, threadbare carpet of a government office corridor: something we believe to agree on, that doesn’t bother, that goes unnoticed, and that quietly gathers dust (which is why people prefer not to look too closely).

ADAM BODNAR and LAURENT PECH (ENG) aren’t afraid to inspect, and they take a closer look at the Venice Commission. The Commission is supposed to safeguard rule-of-law standards across Europe, and its influence is growing. Yet the authors observe that some of the most basic standards are being disregarded in the selection of its members.

In Berlin, the green carpet becomes a little greyer. Last year, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen were accused of redrawing a constituency to their advantage. Although gerrymandering is still rare here, legal standards should be sharpened, argues FABIAN BUNSCHUH (GER).

AI, too, is being sold as neutral: purely objective data (of course), ones and zeros wired together so complexly that outsiders can’t make sense of it – a black box in the hands of private companies on server farms somewhere in the middle of Northern Virginia. Now, ICE wants to use private ad-tech and big-data tools, surprise, surprise. Suddenly, personalised advertising turns into state surveillance. That’s extremely dangerous, warn RAINER MÜHLHOFF and HANNAH RUSCHEMEIER (GER) and call for clear legal limitations.

Unfortunately, taming ICE within the rule of law seems unlikely. It is well known how the Trump administration sees the law – not least because Trump doesn’t tire of spelling it out for us: “I don’t need international law” is just one of his many such bon mots. HELMUT PHILIPP AUST, CLAUS KREß and HEIKE KRIEGER (ENG) describe how the US government undermines international law and what this means for the global legal order.

The latest example: with military options apparently off the table, NATO and the US are now discussing the establishment of sovereign US bases in Greenland. As MARKUS GEHRING and NASIA HADJIGEORGIOU (ENG) explain, such bases would amount to a violation of international law.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++++++

Kritik und Reform des Jurastudiums

Christopher Paskowski & Sophie Früchtenicht (Hrsg.)

Die Rechtswissenschaft steht vor zahlreichen Herausforderungen, von den Gefahren durch den autoritären Populismus bis zur Klimakrise. Dieser Sammelband macht marginalisierte Perspektiven sichtbar, öffnet die Diskussion für interdisziplinäre Ansätze und bietet neben kleinen, „technischen“ Änderungsvorschlägen auch ganzheitlichen Perspektiven Raum.

Hier verfügbar in Print und digital – natürlich Open Access!

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

When it comes to migration, the EU might also find itself at odds with international law. The new draft Return Regulation envisages so-called return hubs and aims to speed up the return process. But this would weaken human-rights standards and punish desperate people, warns BERND PARUSEL (ENG).

Romania, too, punishes desperate people. Because an applicant now faces a minimum seven-year sentence for possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use, a Dutch court has refused extradition to Romania, and the “Tagu” case is now before the CJEU. EMILIA SANDRI (ENG) analyses the Advocate General’s opinion, in which Richard de la Tour proposes a new role for the two-stage test in criminal cooperation.

In neighbouring Bulgaria, the Prosecutor General has been in office since 2023, even though his mandate has expired – and despite an intervention by the Supreme Court. For ADELA KATCHAOUNOVA (ENG), the case is a wake-up call to rethink standing and rule-of-law protections.

The CJEU should also do some rethinking, argue KATARZYNA SZEPELAK and MACIEJ KUŁAK (ENG): the Court prevents NGOs from bringing public-interest litigation. But the treaties allow a different interpretation, according to the authors.

Even more contested is the standing of other, more unusual organisations. A little puzzle: black-and-yellow, but not Amnesty? We’re talking – bees! At the end of 2025, a Peruvian community recognised the legal claims of stingless bees. EVA BERNET KEMPERS (ENG) shows why this case demonstrates that rights of nature are recognised in practice in ways very different from how legal scholarship has imagined them.

Finally, we launched a new symposium this week. “Reflexive Globalisation and the Law” makes research from the eponymous Centre for Advanced Studies at Humboldt University Berlin accessible. The starting point is the idea that the globalisation of law and legal discourse has entered a reflexive phase, characterised by dynamic, multidirectional, and critical knowledge exchange. PHILIPP DANN and FLORIAN JEßBERGER (ENG) introduce the symposium, which continues next week.

Until then, we wish you a great weekend: dye your hair, dust a little, or plant a few bee sanctuaries.

*

That’s it for this week. Take care and all the best!

Yours,

the Verfassungsblog Team

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an e-mail, you can subscribe here.

Congratulations on your provocative article about the role of judges. Judges need not be brave; they just need to have the courage to try to be impartial rather than neutral. Neutrality implies not taking side, but impartiality aims at equity, especially when dealing with groups who are on the fringe of society with no power to have their voices heard. Populists, on the right and on the left, have always tried to use the judiciary for their own questionable political agenda. Your point, however, is well taken: justice has never been blind because those who are more affluent and powerful are also more unjustifiably influential in skewing the judiciary for their own personal gains. My sense is that judges can do more good for society by having moral and legal courage when rendering their decisions than by being allowed to protest and doing so.

Vicente Medina

Thank you for your feedback. As judges, we take sides in our decisions every day by ruling in favor of one party or the other. That is why I do not believe that taking no side can actually be the core essence of neutrality. In my opinion, being impartial is also not enough if it means ignoring the different power relations and resources that our parties have. Am I impartial when I decide that I want to give a minority with an important concern a voice? And I believe that showing courage in decisions and, at the same time, protesting when you see injustice are not exclusive of each other, but are connected.