Using the DSA to Study Platforms

The EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) established a host of new transparency mandates for online platforms. One of the simplest yet most critical allows researchers to collect or “scrape” data that is publicly available on platforms’ websites or apps. This is the first in a series of posts about data scraping and researcher rights under the DSA. It examines who can take advantage of the DSA’s protections, comparing three categories of researchers: vetted academics who receive access to internally held platform data, the broader class of researchers who may use publicly available data, and researchers whose data collection is not covered by the DSA.

Future posts in this series will look more closely at what data these researchers may collect, given uncertainty about what online information counts as “publicly available”. They will also examine how researchers become eligible to collect data, and whether platforms themselves can serve as gatekeepers whose approval is required before researchers can collect even publicly available information. For the DSA’s data access rules to serve their intended purpose as a check on platform power and mechanism for public accountability, it will be important for researchers and regulators to arrive at shared answers to these questions.

Scraping Law

Scraping is the automated collection of data from the user-facing interfaces of websites or apps. The mechanisms for data collection vary, and the term’s precise definition has long been debated. But it is a ubiquitous practice on the Internet. Scraping is the first step Google takes in assembling its web search index. It underlies brand-monitoring and similar services offered by companies like Lithuania’s OxyLabs or Israel’s Bright Data, and is relied on by commercial clients ranging from McDonald’s to Moody’s and Deloitte. Scraping is also widely used for research, ranging from obscure academic work to public interest projects like Bellingcat and the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH). CCDH’s experience illustrates the legal risks scrapers may face. After CCDH used scraped data to document hate speech on X, the platform sued them for millions of dollars under U.S. contract and anti-hacking laws.

Despite major companies’ widespread reliance on – and sites’ tolerance of – scraping, its exact legal underpinnings have always been disputed. In the U.S., researchers who rely on scraping operate in the knowledge that a single cease and desist letter might force them to abandon their project midstream. The same uncertainty often stops universities from approving research in the first place. In the EU, such claims were historically less common. But X has disputed researchers’ rights to data under the DSA in Germany and sued researchers for their reporting in Ireland. And significant uncertainty remains about potential claims under platforms’ Terms of Service, copyright, the GDPR, and other sources of law.

The corporate gold rush brought about by AI is changing this landscape of legal ambiguity and semi-tolerated scraping. Generative AI companies have relied heavily on scraped data for training. Companies that own – or have de facto control over – data have responded with lawsuits and licensing demands. Many have also simply locked down technical access to data on their sites, even for non-profit archival resources like the Internet Archive.

Even as scrapers encounter mounting technical and legal barriers, policymakers are increasingly recognizing scraping’s importance. As I will discuss in a forthcoming article, this isn’t just an issue for AI and other data-driven technologies. The laws that impede scraping can also interfere with major policy goals like platform interoperability. Unclear legal rules about both harmful and beneficial scraping may foreclose important paths forward for the Internet and further entrench today’s incumbents.

The researchers discussed here are just one example. But they are uniquely important, and newly empowered with groundbreaking legal tools to advance the public interest. This post examines how particular researchers and projects will be affected by the DSA. Future posts in the series will examine what data researchers may collect, and whether platforms have the authority to stop them.

The DSA, Research, and Scraping

The DSA depends fundamentally on transparency – not only to regulators or experts, but to the public. As open source software developers sometimes say, with enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow. The same goes for the questions about platform power and public discourse centered by the DSA. By offering data to a wide array of individuals and organizations, the DSA empowers an ecosystem of new sources of information, each reinforcing the others.

The DSA’s transparency measures range from formal platform reports to a public database tracking every content moderation decision reported to users under the law. Perhaps most famously, Article 40(4) allows vetted academic researchers to obtain access to data held internally by Very Large Online Platforms and Search Engines (VLOPSEs). A related provision, Article 40(12), ensures that a wider array of researchers can collect publicly accessible data, including by scraping, in order to assess platform-created risks.

Article 40(12) is a scant ninety-six words. It got relatively little attention in DSA negotiations. But the flexible data collection it permits is essential to the DSA. Scraping, in particular, is uniquely useful for investigating what platforms actually show their users – not just what they claim to show them. Researchers have used laborious new scraping methods to generate the first known random samples of YouTube videos, for example. Scraping also helped establish that the supposedly representative selection of posts in TikTok’s research API is not actually representative. (It is, weirdly, dominated by videos uploaded on Saturdays.) Other researchers used scraping to discover that TikTok’s API omits the company’s own videos, as well as Taylor Swift’s.

In addition to letting researchers check the accuracy of platforms’ disclosures, scraping allows them to look beyond the inevitable limits of structured data from sources like APIs. By way of illustration, DSA regulators’ own API specifications for classifying online content have at times omitted pornography and conflated hate speech with pro-terrorist speech. Scrapers are not stuck with APIs’ classifications, and can instead define their own content or data categories. They can also examine aspects of user experience that are invisible using APIs, like UI design and algorithmic content ranking. This flexibility turns Article 40(12)’s seemingly humble authorizations for access to already-public data into an effective backstop to every other transparency mandate in the DSA. Article 40(12) is also appropriately open-ended about who may collect data. It opens the door to a broadly defined group of non-commercial researchers to do work that serves the DSA’s stated goals.

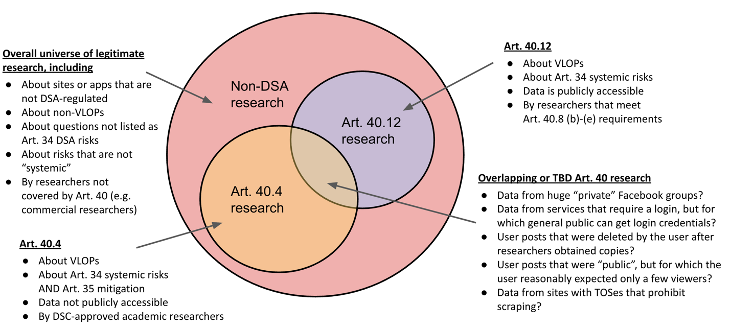

Overall, Article 40 will significantly change the legal landscape – directly or indirectly – for three groups of researchers. Understanding those changes will be essential for those designing and legally vetting research projects. The diagram below illustrates three basic categories of research, which the remainder of this post will discuss in more detail.

Vetted access to non-public platform data under DSA Article 40(4)

DSA Article 40(4) requires VLOPSEs to share internally held data for specific projects vetted by regulators. To qualify, researchers must be affiliated with academic institutions, and meet a list of requirements under Article 40(8), including independence from commercial interests and maintenance of data security. Qualifying projects must address “the detection, identification and understanding of systemic risks” created by platforms in the EU or “the adequacy, efficiency and impacts of [platforms’] risk mitigation measures”. Article 34 lists relevant systemic risks, including threats to civic discourse and fundamental rights; Article 35 lists relevant mitigation measures.

To obtain data access, researchers must apply to national Digital Services Coordinators (DSCs) for vetting and approval. The process for doing so is described in Article 40 and in the Commission’s 2025 Delegated Act.

Access to public data under DSA Article 40(12)

DSA Article 40(12) empowers a much broader group of researchers to use data that is “publicly accessible in [a VLOPSE’s] online interface”, including “real-time data” when technically possible. It covers data that researchers could already have seen simply by looking at public webpages or apps, so in one sense it does not change the information available to researchers. But Article 40(12) significantly expands researchers’ legal certainty and pressure for platform cooperation.

Article 40(12) researchers need not be academics. They are defined in open-ended language as “including those affiliated to not for profit bodies, organisations and associations”. These researchers must meet four basic criteria, a subset of the DSA’s longer list of conditions for vetted academic access to internal platform data. Under Article 40(8)(b)-(e), researchers collecting public data must (b) be independent from commercial interests, (c) disclose their funding, (d) fulfill data protection and security requirements, and (e) use data only as necessary and proportionate to their research purpose. To qualify, research must investigate DSA Article 34 “systemic risk” issues. (Unlike vetted academics, these researchers are not charged with investigating Article 35 risk mitigation.) The DSA does not set out any vetting process for Article 40(12) research, or authorize the Commission to elaborate on its provisions through a Delegated Act.

Article 40(12) has generally been interpreted to encompass three broad data collection methods: APIs, dashboards, and scraping.

APIs

Many past research projects relied on platform-administered APIs. Famously, Twitter withdrew free researcher access to its API in 2023, disrupting major ongoing projects. That development prompted widespread discussion of researchers’ precarious position and dependence on corporate permissions in “the Post-API Age”.

APIs can vastly simplify both the technical process of data collection and researchers’ legal understanding of permissible data use. But they come with downsides discussed above, including vulnerability to errors or omissions by platforms. Researchers using APIs under Article 40(12) will effectively face similar risks to researchers obtaining internal data under 40(4). As pre-DSA experience shows, platform errors sometimes lead to incomplete and non-representative data sets, with devastating consequences for researchers.

Article 40(12) does not spell out specific obligations for platforms to build new APIs, or grant access to existing ones. That said, DSA Recital 98 clearly contemplates platform-administered tools for researchers. VLOPSEs may in any case have strong incentives to build APIs as a means of maintaining control over data collection. By imposing terms of service on researchers, platforms can also seek – understandably – to avoid liability if researchers misuse data.

Dashboards

The second and most ambitious form of Article 40(12) data access is through sophisticated data dashboards similar to Facebook’s deprecated CrowdTangle tool. Recital 98 of the DSA appears to describe Article 40(12) compliance through tools of this sort. Interestingly, the Recital also describes provision of data that many platforms do not currently make public, such as data “on aggregated interactions with content from public pages, public groups, or public figures, including impression and engagement data such as the number of reactions, shares, [and] comments from recipients of the service.”

A 2024 Mozilla Foundation report on platforms’ 40(12) compliance expands on this idea, recommending that platforms provide not only “real-time” information about the present, but “full historical access” to previously available data, including “time-series data about content engagement, account growth, and any other relevant attributes that change over time”. It also recommends development of third party resources that sit outside platform control, including “dashboards, data-donation repositories, and historical archives”. Third parties of this sort might also help researchers comply with the GDPR and other laws.

Scraping

The most quotidian – but perhaps also most essential – means of data access under 40(12) is scraping. Article 40 does not mention scraping by name. The DSA’s only mention of it is in a recital saying platforms need not count “automated bots and scrapers” among monthly active users. (A reference that, interestingly, seems to recognize the existence of scraping that platforms know about and tolerate.) However, the Commission has twice identified “scraping” as a required means of data access under Article 40(12), in binding commitments entered by AliExpress and in preliminary findings of DSA infringement by X.

Unlike Article 40(4)’s vetted researcher provisions, Article 40(12) establishes no role for national DSCs. Formal regulatory authority remains with the Commission. But the DSA does not authorize the Commission to expand on Article 40(12) through a Delegated Act, as it did for vetted academic research. The Commission says that it will not review individual disputes about data access under 40(12), but instead monitor platforms’ overall compliance to “assess whether there is a suspicion of systemic infringement”. In addition to the X and AliExpress investigations, the Commission investigated Meta and TikTok and issued preliminary findings of Article 40.12 violations by both companies.

In practice, it seems likely that researchers may bring platform scraping questions to DSCs, despite their lack of formal authority. That could happen because researchers use scraping as a first step in determining what non-public data to request under Article 40(4), or describe future scraping as part of an overall project submitted for approval under Article 40(4). Researchers might also approach DSCs informally, or even bring complaints under DSA Article 53, if their scraping is blocked by platforms. The Commission’s FAQ for researchers takes a pragmatic approach, encouraging them to “reach out either to DSCs or to the Commission” about difficulties obtaining data under Article 40(12).

Non-DSA research

The DSA and Article 40 have understandably been a major focus among platform researchers in recent years. But a huge array of important online research falls outside the DSA. This includes collection of data from non-VLOPSE platforms, or from sites and apps run by news publishers, corporations, governments, political parties, religious organizations, and more. In addition, data collected from VLOPSEs will not qualify under 40(12) if the research project does not concern DSA-enumerated risks.

A project collecting oil companies’ public statements about pollution or climate change, for example, would probably fall largely or entirely outside of Article 40. The same goes for a linguistics project tracking the emergence and normalization of slang. For that, a researcher might want to scrape sites like Urban Dictionary, Telegram, or 4chan to identify early uses of a particular term; scrape Reddit or Instagram to track its growing popularity; and scrape news sites to show normalization. For that hypothetical project, only the Instagram data would potentially be covered by Article 40(12) – and then only if it could be connected to a harm listed in the DSA. The project would stand a better chance of DSA coverage if it focused, for example, on derogatory slang describing people with disabilities (which affects Article 34 risks to human dignity and non-discrimination) and on the problems created by platform content moderation and ranking (rather than users’ independent choices or offline behavior).

Non-DSA researchers won’t be directly protected by Article 40, but they may still benefit if the DSA drives more flexible or clearer interpretations of other laws. Courts assessing the rights of DSA researchers might, for example, arrive at research-protective interpretations of the text and data mining exceptions to the DSM Copyright Directive, national contract law and terms of service, or the GDPR’s “legitimate interests” basis for processing personal data. If interpretations of these other laws open the door to legitimate research generally, and not solely under the DSA, it will benefit the broader research community.

In the meantime, the clearer legal path created by Article 40 could come at a cost to non-DSA projects. Our hypothetical linguistics researcher might more readily secure funding or IRB approval if she revised her project to focus solely on Instagram – even though she would then be unable to examine cross-platform dissemination. Similar incentives to prioritize regulators’ research priorities have been noted by potential Article 40(4) researchers. In the broader research community, the same considerations could reshape priorities for scraping-based news reporting like The Markup’s, or civil society projects like CCDH’s reporting on X. Ultimately, protecting legitimate online research overall will require navigating legal barriers beyond the DSA.

Conclusion

The DSA opens important opportunities for researchers collecting publicly available data, but also leaves key questions unresolved. Subsequent installments in this series will address other legal questions for scraping-based research under DSA Article 40(12), including the definition of “publicly accessible” data and the role of platforms in vetting or approving research. Answering these questions will provide more clarity under the DSA, and perhaps begin to answer related questions for the larger universe of researchers.

This is a cross-posting with Tech Policy Press.