Between Continuity and a Perforated ‘Cordon Sanitaire’

On the 2024 European Elections

Fears of a radical right-wing wave dominated the debates leading up to the European Parliament (EP) elections. As the final votes are tallied across the 27 EU Member States, it has become evident that the predictions of pre-election polls have partially come true: Far-right parties secured about a quarter of the popular vote, translating into gains of almost 50 seats in the newly elected Parliament, mirroring a longer-term trend at the national level. However, while the far-right has gained seats, the pro-European centre is holding firm. The informal grand coalition of European People’s Party (EPP), Social Democrats (S&D) and Liberals (Renew) is projected to maintain a majority of about 403 out of 720 seats.

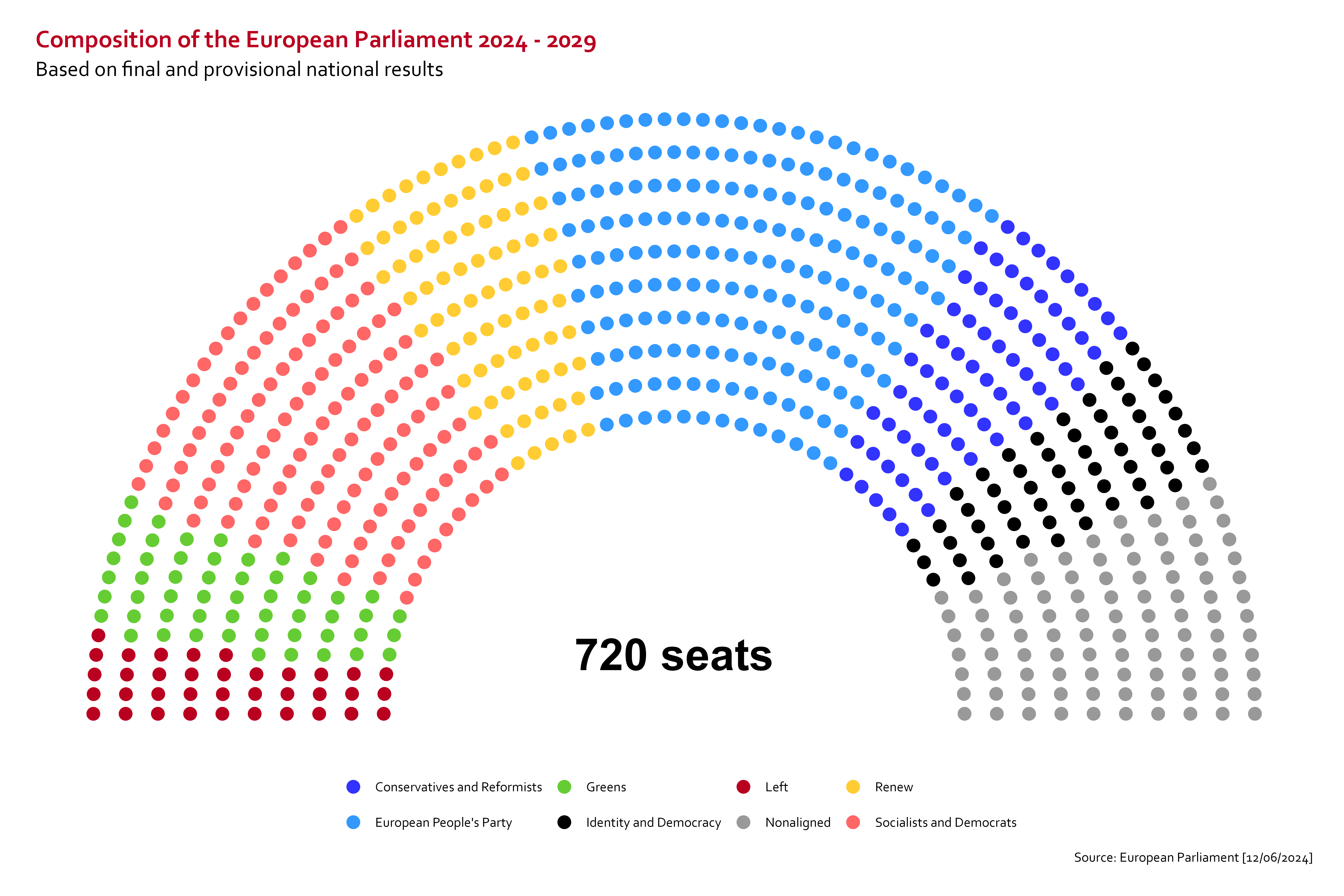

Graph 1: Preliminary results from left to right: The Left 36 seats; S&D 135 seats; Greens/EFA 53 seats; Renew 79 seats; EPP 189 seats; ECR 73 seats; ID 58 seats; NI 97 seats (authors‘ own graph).

What are the implications? While the current results likely indicate by-and-large continuity in the European Parliament, including an ongoing shift to the right on contested issues such as migration or climate policy, they had heavily disruptive consequences on the national level, which in France has resulted in snap parliamentary elections. This will have pronounced impact on the balance of power in the (European) Council and on the EU as a whole.

Far right: No landslide but consolidation

While the elections have not led to a landslide shift to the right, there is a notable consolidation of far-right parties at the European level. Vote shares for these parties have increased or remained stable across almost all Member States. Consequently, the number of MEPs sitting in the European Conservative and Reformists (ECR) and Identity and Democracy (ID) – the two far-right groups in the EP – is set to increase significantly. Whereas the composition of the political groups remains in flux, as will be discussed below, the ECR is even on track to emerge as the third-largest group in the new Parliament. This means two things.

First, there is pressure on the centre to shift to the right. The EPP, which has already run on more right-leaning narratives and policies during the campaign, performed strongly and was even able to add some seats. While the second-largest group, the S&D, remained relatively stable in size, the Liberals and Greens lost big, with the latter even shrinking from the fourth-largest to the sixth-largest group with 53 seats (from 71 seats). Given this new constellation, it has become virtually impossible for the progressive parties to organise majorities without the EPP, as had happened in some cases in the previous Parliament. This means that the EPP is poised to play an even more central role than it has before. This raises the question of the extent to which the EPP will continue to move closer to the positions of the ECR and engage in issue-specific cooperation, especially with Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni’s party, in contested policy areas such as migration and climate.

Second, these results will not only influence the dynamics within the EP but also bear pronounced impacts on governing coalitions at the national level, and hence on the balance of power in the (European) Council. Particularly, ECR leader Georgia Meloni received strong political tailwind on both the European and national stages, as her far-right Brothers of Italy party consolidated its position as the country’s dominant political force. Her success stands in stark contrast with the electoral (under-)performance of her counterparts in Germany and France, who saw their political standings significantly weakened. In France, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National secured twice as many seats as Macron’s Renaissance party, prompting him to call for snap parliamentary elections – a move widely seen as very risky, if not suicidal.

But it is also important to note that this is not the whole story. While the European elections represent a mosaic of 27 national elections, much of the initial attention has centred on the results in Germany and France, where incumbent government parties were trumped by far-right parties that gained a significant number of seats. In a similar vein, the weak performance of the green parties in these two countries disproportionately drove the losses of the EP fraction of EFA/Greens, representing 14 out of the group’s lost 19 seats. These results will undoubtedly shape domestic politics and EU policymaking. But it should not be overlooked that there are also other developments across the continent: Green and left-leaning parties performed very well in the three Nordic EU countries, while the vote share of national far-right parties fell short of expectations. Also, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán is facing a newly emerged political challenger, leading to his ruling Fidesz party’s poorest-ever European election performance, while the parties of the Polish ruling coalition under Prime Minister Donald Tusk achieved a strong result.

Von der Leyen’s path to power: The perforated ‘cordon sanitaire’

The EPP emerged as the clear winner of these elections, which positions EPP lead candidate Ursula von der Leyen as the frontrunner to secure a second term at the head of the European Commission. Yet, despite a seemingly solid majority of EPP, S&D, and Renew in the Parliament, her path to re-election is not without its challenges.

In a first step, she needs to receive approval from a qualified majority of the 27 EU leaders in the European Council – composed currently of 11 leaders hailing from the EPP, five from S&D, four from Renew, two from ECR, one from ID and four independent – at the end of June. While the French side had strategically floated the name of former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi as a potential alternative in recent months, Macron’s call for snap parliamentary elections makes it unlikely that the French President will seriously attempt to torpedo von der Leyen’s bid. Instead, she is well-positioned to receive the endorsement of the EU capitals based on a package deal involving future political priorities as well as the distribution of top jobs and key Commission portfolios among the Member States and political groups.

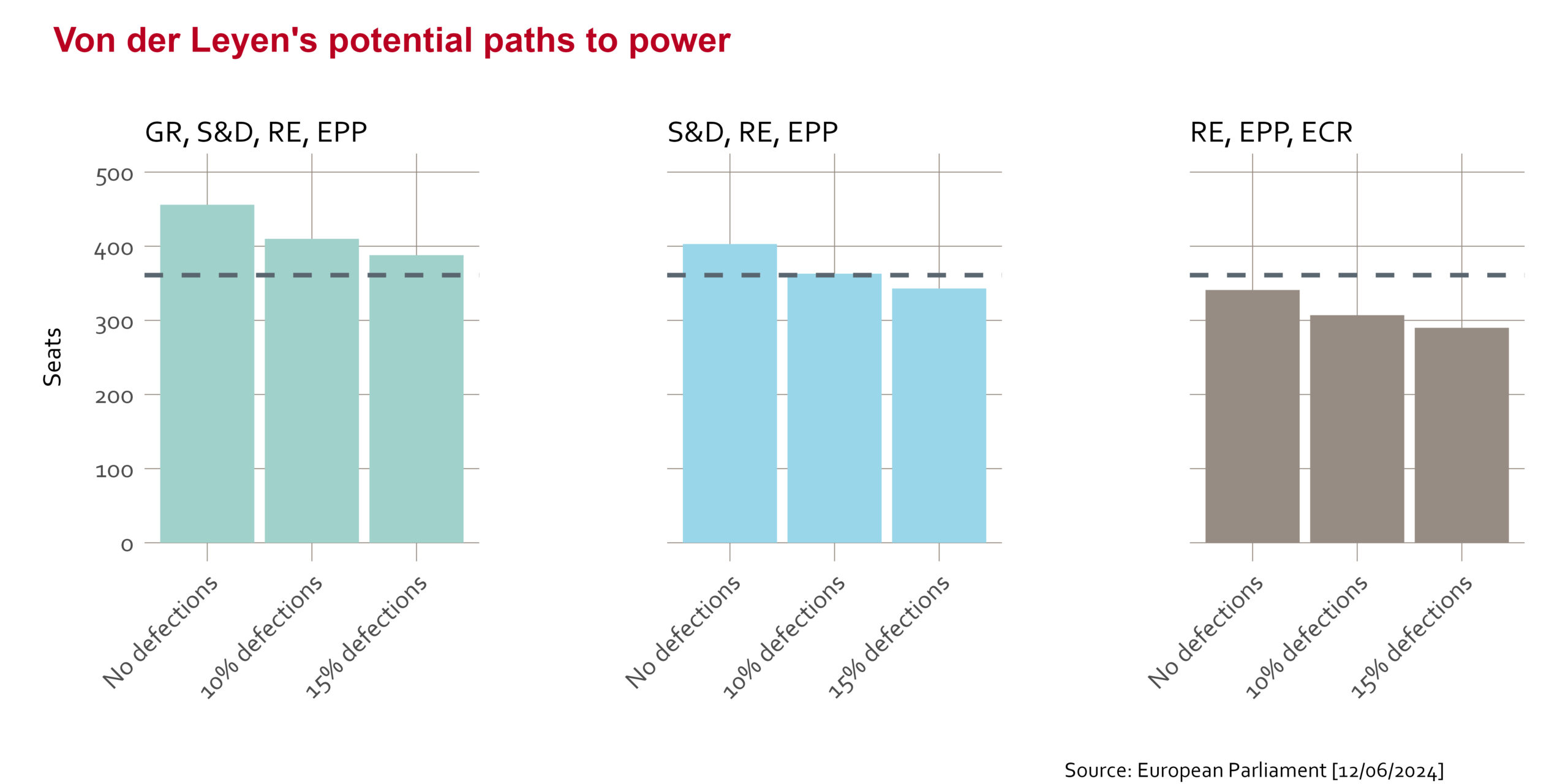

The second step – securing the majority of 361 votes for the parliamentary confirmation – is anticipated to pose the bigger challenge. The general expectation is that von der Leyen must prepare for defections of 10-15 percent across the three political groups of her centrist camp. As such, the French Republicans member of von der Leyen’s own EPP – have already announced that they will not back her bid for Commission Presidency. This may squeeze the existing buffer of around 42 votes, potentially turning reliance on her informal three-way coalition into a high-risk undertaking. This is especially true, as the nomination procedure only allows for one shot; if a candidate fails to gather enough votes, EU leaders need to nominate a new candidate.

Graph 2: Majorities for von der Leyen‘s confirmation vote in cases of no, 10% or 15% defections across different coalitions (authors‘ own graph).

In light of this, von der Leyen will likely reach for additional support from other political groups. Essentially, this leaves her with two other paths to power. Either she continues courting parts of Meloni’s far-right ECR group, risking alienating her coalition partners, S&D and Renew, which have prominently ruled out any form of cooperation with the far-right in the EP. Or she seeks support from the Greens, whom parts of her own party family consider as the main ideological enemy. In any event, as the confirmation vote is secret, it will not become immediately clear who has voted for her. The confirmation vote also has no bearing on later cooperation by the EPP with other groups on specific files: Different than in national parliaments, majorities are more fluid in the European Parliament and organized flexibly according to the dossiers at hand.

In the run-up to the elections, von der Leyen fueled speculations about a possible EPP-ECR alliance by not ruling out cooperation with MEPs from Meloni’s national party in the new Parliament. Instead, the EPP had famously put forward the criteria of ‘pro-Europe, pro-Ukraine and pro-rule of law’ as cooperation conditions. But the day after the elections, the group’s secretary general, Thanasis Bakolas, swiftly dismissed the possibility of a formalized cooperation to secure a confirmation majority. In the same breath, he emphasized that this was not a categorical rejection of working with Meloni’s party in the EP, explicitly leaving the door wide open for future ad hoc right-wing alliances on high-stakes policy files. These statements indicate two things. First, the EPP will likely try to avoid being pushed into any narrowly defined coalition agreement to maintain its strong position, enabling it to form flexible majorities based on specific issues. Second, they underline that, while the EPP is somewhat backpaddling on openly promoting cooperation with certain far-right parties, possibly because of the vocal resistance of their centrist coalition partners, the publicly declared ‘cordon sanitaire’ between centre-right and far-right is heavily perforated, not only at the national and regional levels, but also at the European level.

The Greens represent a potential partner within the democratic mainstream for the EPP. As election results were coming in, the hard-hit Greens were quick in voicing their willingness to back a centrist coalition and clinch a second von der Leyen Commission. In return, they demand guarantees that there will be no backpedalling from European Green Deal legislation. While von der Leyen has no intrinsic interest in dismantling the Green Deal, one of her main legacy projects, aligning the partly antagonistic positions of large segments of her EPP and the Greens on core climate files in the areas of agriculture, nature, and transport will be no easy task. Yet, two factors might work favourably towards this path: First, the Greens are not in a strong negotiation position, which will impact how much hardball they can play. Second, von der Leyen will not only need to strike a balance with the Greens on these files but also with the S&D group. This might open room for constructive compromises, as the latter is pushing for Spain’s deputy minister Teresa Ribera to follow in the footsteps of former Green Deal architect Frans Timmermans and to take up the job of updating the EU’s green policy mix.

Formation of political groups: Negotiating the final picture

Much is – four days after the elections – still in flux. In fact, one of the many peculiarities of the European elections is that it is not only the results of the popular votes that determine the final outcome, but almost as important is the formation process of the political groups afterwards as they can still sway the results in one direction or another. This is crucial not only for the strength of the individual groups but might also affect the EPP’s ability to frame the ECR as a ‘moderate’ partner on the right. Justifying an issue-based partnership would become more complicated if, for example, ECR would include Le Pen’s Rassemblement National.

While for most MEPs their membership in a political group is clear, there are still about 100 non-aligned MEPs that will look for a possible political home in the coming weeks, along with any potential defectors from existing groups. This includes, on the far-right side, the German AfD (15 seats) after their exclusion from ID shortly before the elections, Hungarian Fidesz (10 seats), which left the EPP in 2021, and Polish Konfederacja (five seats). On the left populist side, it includes Slovakian Smer (five seats), whose S&D membership is suspended, the new German BSW (six seats) and the Italian Five Star Movement (eight seats). Membership in a political group is important for MEPs because it guarantees them political posts and influence in the form of vice-presidents, committee chairs and rapporteurships. Equally, there is an interest on the side of the political groups to recruit as many new members as possible to boost their bargaining powers and secure more funding. This means that, until 4 July, when the final compositions of the groups will have to be declared, there will be ongoing negotiations with unpredictable outcomes.

To illustrate just how fluid and complex the picture is: According to current projections, Renew is ahead of ECR with only six seats. If Czech Andrej Babis’ ANO 2011 party (seven seats) leaves Renew and joins ECR as has been floated, the latter would overtake Renew as third-largest group. With the likely addition of Fidesz to their ranks, ECR would increase from currently predicted 73 seats to 90 seats, while Renew would drop to 72. If the AfD rejoins ID ranks – a move rather unlikely to be accepted by Le Pen given the upcoming French national snap elections though – ID would rise from 58 to 73 seats, potentially overtaking Renew in this scenario. If pan-European Volt (five seats) switches to Renew, this would bring up Renew again to 77, to the detriment of the Green/EFA group, where they previously sat.

Speculations on the composition of the groups, and in particular how the far-right parties will organize, abound. The discussions concern not just the question of alignment of the NI to existing groups but also the possible formation of new far-right groups. The requirement for political groups is 23 MEPs from seven Member States. At least theoretically, all far-right parties, currently divided into ID, ECR and NI, could, in this vein, merge into one big “super far-right group“, which would make them the second-largest group in Parliament after the EPP. But in practice, this is very unlikely to happen. The individual right-wing national parties are too fragmented and divided on policy to band together, with a lot of animosity between them. They barely even get along on the national level as can be currently witnessed in France, where in-fightings have led to four out of five recently elected members of Reconquête (ECR) thrown out of the party.

Continuity in the Parliament, disruption in the (European) Council – Still-stand in the EU?

Overall, the current results likely indicate by-and-large continuity in the European Parliament, including an ongoing shift to the right on contested issues such as migration or climate policy, which had already been evident in the final rows of the outgoing Parliament. The pro-European centre has held and still has a majority. However, the gains of far-right parties across many Member States consolidate their influence at the EU level and mirror the longer-term rightward trend at the national level. How pronounced this rightward shift will be in terms of policy, will hinge on the EPP. The gains by the far-right will put pressure on them to increasingly open up to the latter’s positions. It will be thus all the more important to find constructive compromises within the informal grand coalition and to put together a strong team around the new Commission president, both in terms of Commissioners in the key portfolios and the other top jobs. This is all the more important considering the difficult tasks laying ahead of the EU in the next legislative term, including defense, budget, competitiveness, climate, migration and enlargement.

The much more imminent effects of the election results, however, are felt at the national level, in particular in France and Germany, with detrimental spillover effects in the (European) Council. In Germany, the traffic light coalition has been significantly weakened by the results, while in France, the results of the European elections have triggered snap parliamentary elections. Consequently, neither of the two governments will, with little political backing at home and – in the case of France – a possible parliament in opposition to the President, be in any position in the near future to push for large-scale policy reforms at the EU level. This lack of leadership, combined with an increasing number of member states governed by far-right, Eurosceptic parties – including the Netherlands, Hungary, Slovakia, and potentially Austria in the fall – makes a still-stand in the EU a real risk – only not in the EU institution that was just elected.

This text was published in parallel as a policy brief on the Jaques Delors Centre website.