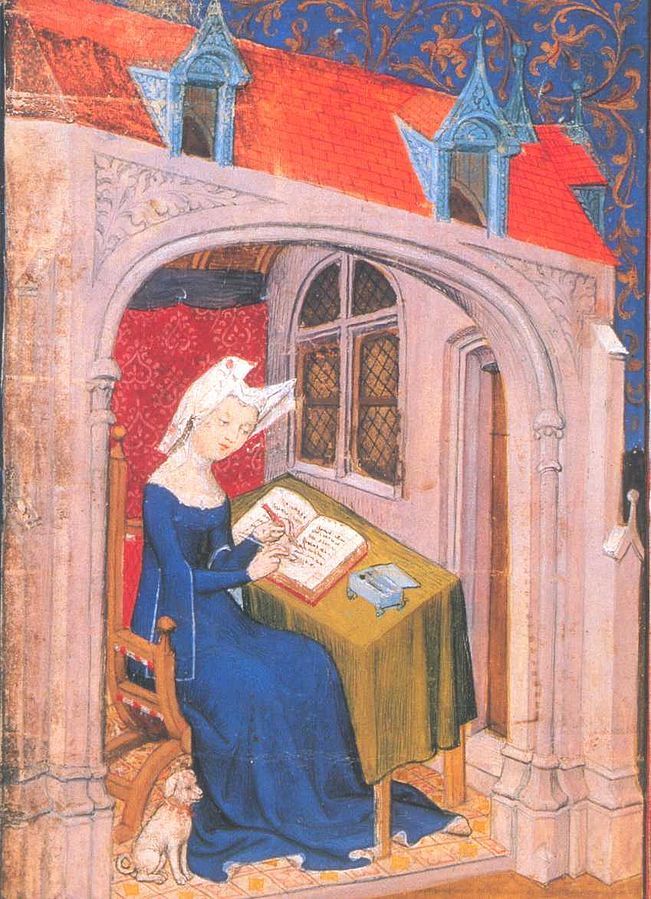

Christine de Pizan

Against all Odds: Feminist Pioneer and Expert on the Law of Warfare in Medieval Europe

“Not all men (and especially the wisest) share the opinion that it is bad for women to be educated. But it is very true that many foolish men have claimed this because it displeased them that women knew more than they did.”

Imagine a setting in a seminar room, where students are attending a course on the designated “classics” of international law, international legal history or schools of thought in international law. They listen to different presentations and engage in discussions on outstanding figures, be it philosophers, scholars, judges or lawyers, and their important contributions to the development of the international legal order. When looking at the so-called “fathers of international law” and other icons of the field, particularly from the (earlier) past, some will not notice anything unusual. By contrast, others may experience a disturbing feeling, as if the picture remains patchy and incomplete. They realize that all of these figures were possibly identifying themselves as men, predominantly white heterosexual men. And all of a sudden, the question arises: Where are actually the women 1) in this picture?

In conversations on missing female voices in the traditional development of international law a repetitive argument given as an explanation for the absence of women as active designers and contributors to international law is that it was simply unusual to find women in certain professions at that time due to the assignment of gender roles and corresponding conduct and activities considered as adequate. There is certainly a great deal of truth in this explanation. Due to the societal roles given and characteristics attributed to women and the corresponding restrictions with regard to access to education, professions, financial resources, land, property and therefore a self-determined life, women simply lacked the capacities, the means and the opportunities to establish themselves as leading philosophers, academics or practitioners.2) To acknowledge the effects of systematic and structural discrimination of women in all their diversity means to visualize the significant hurdles women faced and still face to shape and develop public international law and other legal fields and to pave the way for necessary changes, though it is important to highlight that such discrimination manifested and manifests itself differently depending on the intersectional situation of the specific woman.3) In this sense, the limited space for recognition of outstanding women was mostly occupied by white, Western, middle- to upper-class women.4)

Nevertheless, the argument that the absence of women was a normal side effect of the traditional social circumstances at that time could also serve as an excuse to overlook, ignore and make women invisible, who have actually played a crucial role as active designers of the international legal order – decades and even centuries ago. Thereby, those trailblazing female figures who actually succeeded in significantly contributing to the development of international law despite the abovementioned hurdles women faced at that time, are denied the recognition they deserve,5) which is also owed to a patriarchal system that operates covertly and therefore mostly unnoticed. In this vein, Mary Beckeremphasized that “patriarchy as a social system within which rules operate – a social system that is male-centered, male-identified, male-dominated, and obsessed with power over and control of others – remains entirely invisible. Patriarchy can be challenged, but only by those who see it.”6)

Important academic projects, such as the works of Immi Talgreen7) and Rebecca Adami and Dan Plesch,8) and other individual contributions have brought several of the many trailblazing women and their contributions to international law out of the shadow of their male colleagues, thereby actively confronting the patriarchal patterns that foster their invisibility and non-recognition. This blogpost seeks to add to these important works by kicking off a new column with the Verfassungsblog on Outstanding Women of International, European and Constitutional Law to make very diverse female actors, their contributions as scholars, activists, judges, lawyers, philosophers and in other roles to these fields as well as their intersectional experiences more visible, known and recognized.

Standing out in the Medieval: Multitalented Author and Feminist Icon Christine de Pizan

One of the women that have for the longest time been overlooked and undervalued in legal scholarship,9)and who possibly fell victim to the idea that women, particularly through the medieval era, simply lacked the means, capacities and opportunities to make a significant contribution to the development of public international law, is Christine de Pizan. In recent years, multi-talented Pizan has caught more attention, particularly through the portrayals of her work on the law of war by Franck Latty, who highlighted the significance of her work for the legal discipline (see here and here), following Ernest Nys and others in acknowledging her oeuvre. Pizan as an outstanding intellect was a living proof that even during the Middle Ages women were able to lead extraordinary lives that very much departed from paradigms existent at that time, which were ruling and pervading the entire society.10)

In the Middle Ages, the position of women in its connection to autonomy, quality of life and opportunities as well as corresponding societal restrictions were very much dependent on the specific time – the situation of women was changing, but in principle improving from the early to the late middle ages – and the class (clergy, nobility and serfs) they belonged to. Nonetheless, the position of women and how it was articulated was predominantly influenced by the church and the aristocracy, sustained by a feudal system that maintained every person in his*her position.11) Officially women counted as second-class citizens and were generally subjected to male control over their bodies, behavior and interests during the Medieval time. In this sense, “[t]he fact that governed her position was not her personality but her sex, and by her sex she was inferior to man.”12) Therefore, a woman was in principle relegated to the home and the field to produce children and assist her husband in his work. Eileen Power therefore highlighted that “the great majority of women lived and died wholly unrecorded as they labored in the field, the farm, and the home.” Not so Christine de Pizan.

The First to live by her Pen: Privileges and Hurdles at the French Court

Pizan was born in the late Middle Ages, in 1364, in the Republic of Venice, Italy. The foundation for much of the opportunities and successes of a young women that would become a virtuous and versatile court writer, author, poet and an early icon of feminist writings were probably laid in her childhood. Her father, Tommasso de Benvenuto da Pizzano, a physician, court astrologer and Councillor of the Venetian Republic, accepted an appointment as astrologer of the French King, Charles V, so that the family moved to Paris in 1368, where Christine spent a studios, but also pleasant childhood with the benefits and access to materials that came with the rich cultural background at the court, which also shows the very privileged environment she grew up in.13) Nonetheless, Pizan was early on confronted with the stereotypical assignment of gender roles in the Middle Ages. Looking back at her childhood, Pizan herself noted in her work Le Livre de la cité des dames (“The Book of the City of Ladies”):

Your own father, who was a great astrologer and philosopher, did not believe that knowledge of the sciences reduced a woman’s worth. […] Rather, it was because your mother, as a woman, held the view that you should spend your time spinning like the other girls, that you did not receive a more advanced or detailed initiation into the science.14)

Still, history has shown that despite of these adversities Pizan managed to build what can actually be called a career, even despite her marriage at the age of 15. While her husband, Étienne du Castel, who became a royal secretary, was chosen by her father, the couple, who had three children, generally lived a happy life.15) After ten years of marriage, Étienne du Castel fell victim to the plague in 1389, not long after the death of her father, both of which changed the course of her rather privileged life, as she was further burdened with perennial law suits related to responsibilities for her husband’s property.16) While her situation did not force her to remarry, it was still due to pure necessity that Christine took up writing in order to support her mother, children and a niece.17)Out of a personal tragedy she thereby became the first woman to make a living exclusively from her pen, which led to her title of “first professional woman of letters in Europe”.18) At the beginning of her “career” as a court writer she started with book production and copying manuscripts, before embarking on her own writing.19) She first focused on verse in the form of ballads that met with much success as they particularly pleased wealthy members of the court, many of whom became her patrons, such as Queen Isabeau of Bavaria, Louis I, duke of Orléans, the younger brother of King Charles VI, Jean de France, duke of Berryand Philip II, duke of Burgundy.

“La Querelle de la Rose”: Intruding the Masculine Scholarly World from Verse to Prose

From her 10 volumes in verse, one piece – L’Épistre au Dieu d’amours (“Letter to the God of Loves”) from 1399 – stands particularly out as one of the first written feminist contributions. According to the philosopher Simone de Beauvoir it was “the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex.”20) Pizan wrote L’Épistre au Dieu d’amoursand other works against the misogynist views expressed, inter alia, in Ovid’s Ars Amatorial (“Art of Love”), Matheolus’ Liber lamentationum Matheoluli (“The Lamentations of Matheolus”),21) particularly addressing Jean Meun’s Le Roman de la Rose (“The Romance of the Rose”),22) one of the most read books of her time,23) in which women were not only a subject discussed between men,24) but also depicted as seducers and deceivers, as “depraved and malicious creatures”.25) Pizan criticized the work for its defamation of women through bawdy language and its justification of rape and thereby contributed to the famous ‘Querelle de la Rose’, a renowned literary controversy in the form of letter exchanges among key figures of the early-fifteenth century French literary community.26) Christine joined this conversation with inter alia three royal secretaries as the first woman to do so and thereby intruded and interfered with the masculine scholarly world,27) challenging the male admirers of the text. Not without humor, and possibly with a deliberate attempt to establish female authority through her contributions,28) she defended her views:

And let it not be imputed to me a folly, or arrogance, or presumption for me to dare, a mere woman, to reprehend and to criticize an author of such subtlety, whose work is acclaimed by praise, when he, a single man, dared to undertake to defame and blame without exception an entire sex.29)

Christine continued her productive writing with moving from verse to prose, including a piece of what today could be called a “biography” on the deceased Charles V at the request of Philipp II. Le Livre des fais et bonnes meurs du sage roy Charles V (“Book of the Deeds and Good Character of the Wise King Charles V”) from 1404 can be read as a homage to the cultural capital he had brought to the court as an ideal leader committed to learning,30) but also as female pedagogical advice of good practices and ethical ideas to young princes and male sovereigns.31) The utilization of figures and personae of female pedagogues continues in one of her most famous works from 1405, Le Livre de la cité des dames (“The Book of the City of Ladies”), in which Pizan literarily creates a city inhabited exclusively by legendary women from past and present known for their heroism, talent and virtue, a royaume de féminie or feminist utopia,32) a city where women are appreciated, defended and protected from misogynistic attacks.33)

Ahead of and Caught in Her Time: The “Book” and the “Treasure” of the City of Ladies

In Le Livre de la cité des dames Pizan enters into a conversation from an entirely female perspective with three allegorical figures – Reason, Justice and Rectitude as the three virtues for success – to show that women are equal to men in terms of military skills, political leadership, art, ingenuity and intelligence, thereby not only rejecting misogynist prejudices, but also providing female readers with self-confidence and self-worth.34) She demonstrates “how female nature has been misconstructed within male misogynistic discourse”, while at the same time vindicating “women as intelligent, moral beings who are capable of being educated and of making significant social and political contributions.”35) Christine demonstrates that if women are part of the conversation, it becomes difficult to maintain stereotypes that work to their detriment.36) By repeatedly naming herself in a gendered form she becomes “an active agent of her own sentences” and constructs “an alternative authority within the textual practices she has inherited.”37)

Her second women-centered work of 1405, Le Livre des trois vertus (“The Treasure of the City of Ladies” or “The Book of the Three Virtues”), can be read as a handbook of moral instructions for women of all social spheres in the medieval time – from princesses and nuns to prostitutes as well as married and unmarried women – to achieve virtue within the current social order,38) with very practical advice on how to dress, speak and behave.39) She wanted to demonstrate that all women were capable of diligence, humility and rectitude and intended to help them navigating “the perils of a society often hostile to their gender.”40) While the work puts a spotlight on the relevance of education for all women and seeks to spark women to strive for virtue even within the constraints of the current social order,41) the progressive feminist approach that shines through in Le Livre de la cité des dames seems to lose force in both rhetoric and content in the realm of Le Livre des trois vertus.42)

Had heroism and agency played a decisive role in Le Livre de la cité des dames, Christine did not prompt or encourage women to leave the societal places and roles assigned to them and to overcome limitations of current society in order to pursue the positions of leadership and realization of their full potential, which Le Livre de la cité des dames had shown them they were capable of, but rather advised women to “accept their lot with patience and submit to male control […].”43) This stands also in remarkable contrast to the space, role and authority she claimed for herself as a woman, which has led to criticism of her privilege and conservatism, some questioning her title of a “mother to think back through.”44) Even though Pizan in these two works might not have intended to revolutionize current society in enabling a rearrangement of societal roles and spaces, she nonetheless demonstrated that women are neither inferior to nor worth less than men, but rather equally capable, intelligent and talented, providing sufficient examples that serve as role models for her female readers. Confronted with widespread misogynist sentiments in the many literary and philosophical works she had studies,45) she decided to rise from the resulting despair to use her pen virtuously to dismantle and refute anti-feminist prejudices,46) which can also be seen in her biographical work L’Avision de Christine.47)

Invading Male-dominated Terrain: “The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry”

Besides her literary attempts to defend and empower women, Pizan did further not shy away from diving deeper into a sphere that was, and possibly still is, considered as particularly male: the art and law of warfare. With Le Livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie (“The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry”) from 1410, Pizan created a manual for those able to start and wage war, combining the art of warfare (strategies and techniques of war, abilities of combatants etc.) with the rules governing the law of war at that time.48) While in Le Livre des trois vertus she had advised princesses to avoid the outbreak of war through diplomatic means and further acknowledged the great evils associated with it, such as rape, executions, massacres and destruction in her manual on warfare,49) she still saw war as a legitimate tool and duty – but only of sovereign princes – if undertaken for a just cause and therefore permitted by God.50)

According to Pizan, just causes for war, meaning those that rest on and are limited by civil and canon law, are i) “to maintain law and justice”, for instance in defense of the church, an ally or a vassal, ii) “to counteract evildoers who befoul, injure, and oppress the land and the people” and iii) to recover lands, lordships and other things stolen or usurped for an unjust cause […].”51) Pizan considered two other reasons to wage war as those of will and therefore outside the law, namely “to avenge any loss or damage incurred” and “to conquer and take over foreign lands or lordships.”52) While public international law did not exist at that time, the arguments presented very much relate to current ius ad bellum and exceptions to resort to force, for example in situations of self-defense and corresponding assistance. Furthermore, Pizan also covered what today would be considered ius in bello, the law regulating the deeds of arms or conduct of hostilities. She refers to unacceptable and forbidden tricks as well as the protection of both prisoners of war and civilians, highlighting that “it is against right and gentility to sly the one who gives himself up” and that “those who engage in warfare may be hurt, but the humble and peaceful should be shielded from their force.”53)

Pizan’s Le Livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie, which was subsequently presented as the work of a man,54) has predominantly fallen into oblivion because of existing and continuing gender biases operating to the detriment of a Medieval woman, who left aside “weaving, spinning, and household duties”55) to deal with a topic considered as particularly masculine. Although Pizan built on and made use of relevant works of her predecessors,56) reflecting a common practice before, at and after her time, she explicitly incorporated Honoré Bovet and his work (Battle Tree) into Le Livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie,57) and generally acknowledged to “have gathered […] facts and subject matter from various books to produce this present volume.”58) With her “ambition to cover the theme of war in its double technical and legal dimension”,59) Pizan managed to fill “an intellectual and practical void and signs the first French full survey on military matters.”60) While Latty has a point in avoiding parental metaphors (“father” or “mother” of international law) that suggest international law can be traced back to a single or at least very few persons,61) it still seems appropriate to put Pizan’s work, whether as that of a “mother of international law”62) or not, at eye level with her male predecessors and successors, also because she presumably was the first woman to have written on the art and law of war and in such detail, long before the so-called “founding fathers of international law”.63)

Pizan supposedly retired to a convent where she lived for the last ten years of her life, feeling despair and depressed in light of civil war and English occupation.64) In 1429, however, Christine seemed to regain optimism and find inspiration in the military victory of another outstanding woman, Jeanne D’Arc, to whom she dedicated the poem Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc (“The Tale of Joan of Arc”) in 1429.65) Even though Pizan presumably died before Jeanne D’Arc’s execution in 1431,66) she nonetheless heralded “the fact that a young maid was able to accomplish something that many political men were unable to do.”67) In light of the breadth and depth of her literary works that were often ahead of a time, where women were even more socially restricted and caught up in their assigned roles, it is due time to recognize and celebrate a brilliant and groundbreaking writer and “the first woman in the Middle Ages to confront head-on the tradition of literary misogyny or anti-feminism that pervaded her culture.”68) Thus, “after decades of collective amnesia”,69) the gifted author, philosopher and pedagogue Christine de Pizan should be invited into the auditoriums and seminar rooms of our universities to inspire our teaching and research with her feminist thoughts, literary talent and legal expertise.

Further Readings:

- Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies (originally Le Livre de la cité des dames from 1405, Rosalind Brown-Grant (tr and ed), Penguin Books 1999).

- Christine de Pizan, The Book of the Deeds of Arms and Chivalry (originally Le Livre des faits d’armes et de chevaleriefrom 1410, Sumner Willard and Charity Cannon Willard (tr and ed), Pennsylvania State University Press 1999).

- Christine de Pizan, The Treasure of the City of Ladies (originally Le Livre des trois vertus from 1405, Sarah Lawson (tr and ed), Penguin Books 2003).

- Charlotte Cooper-Davis, Christine de Pizan: Life, Work and Legacy (Reaktion Books Ltd 2021).

- Marylin Desmond (ed), Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference (University of Minnesota Press 1998)

- Franck Latty, ‘Christine de Pizan: The Law of Warfare as Seen by a Medieval Woman’, in Immi Tallgren (ed), Portraits of Women in International Law: New Names and Forgotten Faces? (Oxford University Press 2023).

Further Sources:

- Christine de Pizan: from medieval writer to feminist icon, History Extra podcast, with Charlotte Cooper-Davis, May 2022, available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2WnfIu7dB3CkxKHG7w4AE9

- Christine de Pizan, The Medievalists, available at: https://www.medievalists.net/2019/12/christine-de-pizan/.

References

| ↑1 | By using the term women, this contribution refers to the entire diversity of those identifying themselves as women and follows therefore a trans* and queer inclusive understanding. This is also based on the conviction that both gender and sex are socially constructed. See, inter alia, Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity [1999] 1–32; Brenda Cossman, ‘Gender Performance, Sexual Subjects and International Law’ [2002] 15 Canadian Journal of Law & Jurisprudence 281; Dianne Otto, ‘Queering Gender [Identity] in International Law’ [2015] 33 Nordic Journal of Human Rights 299. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See, inter alia, Caroline O. N. Moser, ‘Planning in the Third World: Meeting Practical and Strategic Gender Needs’ (1989) 17 (11) World Development 1799, 1801, 1803, 1812-1813; Maxine Molyneux, ‘Mobilization without emancipation? Women’s interests, state and revolution in Nicargua.’ (1985) 11 (2) Feminist Studies 227, 232-233; V. Spike Peterson and Anne Sisson Runyan, ”Global Gender Issues” (Avalon Publishing 1993) 62, 77; Virginia Woolf, A room of one’s own (Hogarth Press 1929) 19-21, 72-74, 90; Catherine Kessedjian, ‘Gender Equality in the Judiciary – with an Emphasis on International Judiciary’ in Elisa Fornalé (ed), Gender Equality in the Mirror: Reflecting on Power, Participation and Global Justice (Brill 2022) 195, 202-205. |

| ↑3 | With regard to the intersectional approach see particularly Kimberlé Crenshaw, ‘Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics’ (1989) University of Chicago Legal Forum 139, 140. In this sense, an intersectional approach as applied by Crenshaw has more generally been understood as the “idea that when it comes to thinking about how inequalities persist, categories like gender, race, and class are best understood as overlapping and mutually constitutive rather than isolated and distinct.” Adia Harvey Wingfield, ‘About Those 79 Cents’ (The Atlantic, 17 October 2016), available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/10/79-cents/504386/. See also Adia Harvey Wingfield and Melinda Mills, ‘Viewing Videos: Class Differences, Black Women, and Interpretations of Black Femininity’ (2012) 19 Race, Gender & Class 348, 352. |

| ↑4 | On this one-sided focus see, inter alia, Kimberlé Crenshaw, ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color’ (1991) 43 Stanford Law Review 1241, 1252; Chandra Talpade Mohanty, ‘Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses’ in Chandra Talpade Mohanty et al (eds), Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism (Indiana University Press 1991) 51, 70. |

| ↑5 | Nancy Fraser has described such cultural injustice as being rooted “in social patterns of representation, interpretation, and communication. Examples include cultural domination (being subjected to patterns of interpretation and communication that are associated with another culture and are alien and/or hostile to one’s own); nonrecognition (being rendered invisible by means of the authoritative representational, communicative, and interpretative practices of one’s culture); and disrespect (being routinely maligned or disparaged in stereotypic public cultural representations and/or in everyday life interactions).” Nancy Fraser, Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflections on the “Postsocialist Condition” (Routledge 1997) 14. |

| ↑6 | Mary Becker, ‘Patriarchy and Inequality: Towards a Substantive Feminism’ (1999) University of Chicago Legal Forum 21, 83. See also Catherine Kessedjian who in her explanation for the underrepresentation of women in international courts stated: “Power is still the prerogative of white men aged over 50 years. They have no reason to give up a system that has worked to their advantage for decades. In other words, white men are privileged but they are privilege-blind. Most of them would be the proper vehicle for change.” Catherine Kessedjian, ‘Gender Equality in the Judiciary – with an Emphasis on International Judiciary’ in Elisa Fornalé (ed), Gender Equality in the Mirror: Reflecting on Power, Participation and Global Justice (Brill 2022) 195, 205. |

| ↑7 | Immi Tallgren (ed), Portraits of Women in International Law: New Names and Forgotten Faces? (Oxford University Press 2023). |

| ↑8 | Rebecca Adami and Dan Plesch, Women and the UN: A New History of Women’s International Human Rights (Routledge 2022). See also Rebecca Adami, Women and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Routledge 2019). |

| ↑9 | Cf. Franck Latty, ‘Christine de Pizan: The Law of Warfare as Seen by a Medieval Woman’, in Immi Tallgren (ed), Portraits of Women in International Law, supra note 7, 47. |

| ↑10 | See Eileen Power, Medieval Women (Cambridge University Press 1997) 2. |

| ↑11, ↑65 | See ibid. |

| ↑12 | Ibid. |

| ↑13 | See Charlotte Cooper-Davis, Christine de Pizan: Life, Work and Legacy (Reaktion Books Ltd 2021) 9. |

| ↑14 | Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies (first published 1405, Rosalind Brown-Grant (tr and ed), Penguin Books 1999) 141. See also Cooper-Davis, supra note 13, 8. |

| ↑15 | Cf. Cooper-Davis, supra note 13, 10. |

| ↑16 | Cf. ibid., p. 11. |

| ↑17 | Cf. ibid., 11 et seq. |

| ↑18 | Cf. Jenny Redfern, ‘Christine de Pisan and The Treasure of the City of Ladies: A Medieval Rhetorician and Her Rhetoric’, in Andrea A. Lunsford (ed), Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women and in the Rhetorical Tradition (University of Pittsburgh Press 1995) 74. |

| ↑19 | See how Christine is described as a “entrepreneur” in bookmaking and -trading in Cooper-Davis, supra note 13, 7 et seq. |

| ↑20 | Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex (Vintage Books 1974) 118. Similarly, Eileen Power wrote that “it is not until the end of the fourteenth century that there appears a woman writer determined and able to plea for her sex and to take a stand against the prevalent denigration of women.” Power, supra note 10, 4. |

| ↑21 | For excerpts of the work and how it impacted on Christine de Pizan see ‘Lamentations of Matheolus and Christine de Pizan’ (WordPress 12 August 2015, available at: https://lamentationsandchristine.wordpress.com/. |

| ↑22 | Meun’s work is the second part and therefore a continuation of a piece written earlier by Guillaume de Lorris, see Cooper-Davis, supra note 13, 95. |

| ↑23 | Cf. ibid. |

| ↑24 | Cf. ibid., 102. |

| ↑25, ↑68 | de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, supra note 14, 15. |

| ↑26 | See Julia O’Connell, Grief, Emotional Communities and Anglo-French Rivalry in Late-Medieval English and French Literature (Dissertation 2021) 213, footnote 13. See also Charity Cannon Willard, Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works (Persea 1984) 78-79. |

| ↑27 | Fenster and Carpenter highlighted that “Christine’s rebuke of Meun stirred their proprietary feelings, along with some irritation at her woman’s audacity. She was a feminine interloper in an exclusively masculine discourse, one that flourished between the secretaries and the authors they admired, on the one hand, and among the members of their own group, on the other. The literary practice they represented had never hesitated to write about women, though it rarely did so with the expectation that women themselves might be its respondents.” Christine de Pizan, Epistre au dieu d’Amours, (Thelma S. Fenster and Mary Carpenter Erler, Brill 1990) 5. |

| ↑28 | Maureen Quilligan, The Allegory of Female Authority – Christine de Pizan’s “Cité Des Dames” (Cornell University Press 2018) 26. |

| ↑29 | As cited and translated ibid., 27. With regard to Pizan’s airily humor and deadly seriousness see Joseph L. Baird and John R. Kane, ‘La Querelle de la Rose: In Defense of the Opponents’ (1974) 48 The French Review 298, 299. |

| ↑30 | See Cooper-Davis, supra note 13, 9, 18; Nadia Margolis, ‘Royal Biography as Reliquary: Christine de Pizan’s Livre des Fais et bonnes meurs du sage roy Charles V’, in Jenny Adams and Nancy Mason Bradbury (eds), Medieval Women and their Objects (Michigan University Press 2017) 123. |

| ↑31 | Roberta Krueger, ‘Christine’s Anxious Lessons: Gender, Morality, and the Social Order from the Enseignemens to the Avision’, in Marylin Desmond (ed), Christine de Pizan and the Categories of Difference (University of Minnesota Press 1998) 26, 27. |

| ↑32 | See ibid., 28. See also Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, supra note 14, 15 et seq. |

| ↑33 | Cf. de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, supra note 14, 16. |

| ↑34 | Cf. ibid., 16 et seq. |

| ↑35 | Cf. Krueger, supra note 31, 26-27. |

| ↑36 | See Karylin Campbell, Three Tall Women: Radical Challenges to Criticism, Pedagogy, and Theory (Pearson Education 2001) 7. |

| ↑37 | Quilligan, supra note 29, 16. |

| ↑38 | Cf. Redfern, supra note 18, 73; Krueger, supra note 31, 28. |

| ↑39 | Cf. Sister Prudence Allen, The Concept of Women, Vol. II, The Early Humanist Reformation (1250-1500), Part 2 (William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company 2002) 646. See also Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, supra note 14, 17. |

| ↑40 | Redfern, supra note 18, 73. |

| ↑41 | Cf. ibid., 74. |

| ↑42 | See Krueger, supra note 31, 28. |

| ↑43 | See Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, supra note 14, 17; Krueger, supra note 31, 29. Krueger also argues that the acceptance of societal circumstances is equally present in Le Livre de la cité des dames, ibid., 28 et seq. |

| ↑44 | See Sheila Delaney, ‘“Mothers to Think Back Through”: Who are They? The Ambiguous Example of Christine de Pizan’, in Laurie A. Finke and Martin B. Shichtman (eds), Medieval Texts and Contemporary Readers (Cornell University Press 1987) 177-198. |

| ↑45 | In this sense, Pizan wrote: “All philosophers and poets […] concur in one conclusion: that the behavior of women is inclined to and full of every vice. […] I could hardly find a book on morals where […] I did not find […] certain sections attacking women, no matter who the authors was.” Cited in Redfern, supra note 18, 75. |

| ↑46 | See Krueger, supra note 31, 29. |

| ↑47 | See Christine de Pizan, The Vision of Christine de Pizan (Glenda McLeod and Charity Cannon Willard (trs), Boydell and Brewer 2012). |

| ↑48 | Cf. Latty, supra note 9, 48. |

| ↑49 | Christine de Pizan, The Book of the Deeds of Arms and Chivalry (Sumner Willard and Charity Cannon Willard (tr and ed), Pennsylvania State University Press 1999) 14. See also Daniel Wetham, Just Wars and Moral Victories: Surprise, Deception and the Normative Framework of European War in the Later Middle Ages (Brill 2009) 62 et seq. |

| ↑50 | Cf. de Pizan, The Book of the Deeds of Arms and Chivalry, supra note 49, 14, 15, 17. |

| ↑51 | Cf. ibid., 14, 16. See also Latty, supra note 9, 49. |

| ↑52 | de Pizan, The Book of the Deeds of Arms and Chivalry, supra note 49, 16. |

| ↑53 | Ibid., 169, 172. |

| ↑54 | Cf. Latty, supra note 9, 53. See also reference to a later version, where signs of her name were supposedly erased in Wolfram Schneider-Lastin, ‘Christine de Pizan deutsch: Eine Übersetzung des ‘Livre des fais d’armes et de chevalerie’ in einer unbekannten Handschrift des 15. Jahrhunderts’, (1996) 125 Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur 194. |

| ↑55, ↑58 | de Pizan, The Book of the Deeds of Arms and Chivalry, supra note 49, 12. |

| ↑56 | See Schneider-Lastin, supra note 54, 193. |

| ↑57, ↑59, ↑61 | Cf. Latty, supra note 9, 54. |

| ↑60 | Hélène Bui, ‘Et la gist la maistrie: de l’Arbre des batailles au Livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie’, in Dominique Demartini et al. (eds) Und femme et la guerre á la fin du Moyen Age: Le ‘Livre des faits d’armes et de chevalerie’ de Christine de Pizan (Honoré Champion 2016) 150, as cited in Latty, supra note 9, 54. |

| ↑62 | See Maria Teresa Guerra Medici, ‘The Mother of International Law: Christine de Pisan’ (1999) 19 Parliaments, Estates and Representation 15-22. |

| ↑63 | See Latty, supra note 9, 54 |

| ↑64 | See Allen, supra note 39, 654. |

| ↑66 | Cf. Margaret C. Schaus, Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia (Routledge 2006) 133. |

| ↑67 | Allen, supra note 39, 654. |

| ↑69 | Latty, supra note 9, 55. |