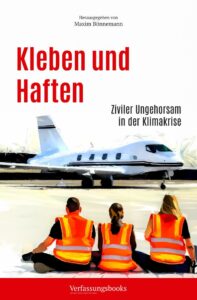

Civil Disobedience in the Climate Crisis

Blocked streets, occupied airports, and a Brandenburg Gate sprayed with paint: Civil disobedience is making a spectacular comeback, in Germany as elsewhere. While the state responds with sometimes drastic severity, legal scholars must reflect. Can civil disobedience be justified in times of the climate crisis? Or is it just ordinary criminality, like that of a criminal organization? The Verfassungsblog has been following the debate from the beginning and is now bringing together selected contributions in book form for the first time. The book is available digitally, open access, and in print starting today. If we haven’t already piqued your interest, we hope to do so by sharing the introduction with you now as this week’s editorial, in a shortened and slightly modified version.

The climate crisis seeds doubt about our many political systems: What if our regular institutions are not designed to combat the climate crisis quickly enough? What if our procedures are too sluggish, our time horizons too short, and our representation mechanisms too limited to address the planet’s destruction in a timely manner? Regardless of how one answers these questions, one insight has become undeniable: the climate crisis is also a crisis of political institutions. Long-established procedures and routines of the liberal constitutional state are under pressure in dealing with the climate crisis. To this day, no significant state emitter has managed to decarbonize to the extent and speed necessary to meet the Paris Climate Agreement goals. The consequences of delayed greenhouse gas reductions were pointed out by the Federal Constitutional Court in 2021 with remarkable clarity: a loss of freedom in almost all aspects of life – especially for young and future generations.

If states fail to lead necessary climate transformation, it will quickly become a problem for the acceptance of political systems. When parliaments and governments fail to convince young generations and vulnerable groups that their interests are adequately considered, both face significant legitimacy losses. In such situations, the suggestion to adhere to regular mechanisms of political decision-making loses its persuasiveness, as it is precisely these mechanisms that are responsible for the structural perpetuation of power imbalances, if not the further escalation of the climate crisis.

The Comeback of Civil Disobedience

Against this backdrop, it is no coincidence that the Federal Republic of Germany is witnessing a resurgence of civil disobedience with the rise of the climate movement. Young people are blocking streets, bridges, and runways. They often resort to what they see as one of their last means to influence the political process: their bodies.

Many see this as a violation of democratic principles, if not even the actions of a criminal organization. In a parliamentary democracy, the argument goes, only words and the established institutionalized majority will should count. Those who question this potentially provide every interest group with the discursive tools to depart from democratic consensus.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++

Am Lehrstuhl für Öffentliches Recht, Europarecht und Rechtsvergleichung (Prof. Dr. Uwe Kischel) ist im Zusammenhang mit dem DFG-geförderten Projekt der Neuausgabe des Handbuchs des Staatsrechts eine Stelle als wiss. Mitarbeiter/-in (50%, E 13 TV-L) zu besetzen, zunächst befristet bis zum 31.3.2026 (Verlängerung möglich). Geboten wird eine hervorragende Arbeitsatmosphäre im lehrstuhlübergreifenden Team, ein spannendes und zukunftsweisendes Projekt sowie die intensive und umfängliche Befassung mit aktuellen Fragen des Verfassungsrechts auf höchstem Niveau. Promotionsvorhaben sind ausdrücklich erwünscht und werden nachdrücklich unterstützt.

Weitere Informationen finden Sie hier.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

Others, however, see this as an example of grassroots democracy in action. They argue that the often somewhat unmotivated reference to the principle of majority overlooks the fact that majorities also have limits. Among these limits is the idea that every decision should be reversible, e.g., amendable through the electoral process. In times of the climate crisis, this very core democratic principle is at stake.

But does this finding justify engaging in civil disobedience? Or are people who break the law out of desperation over the climate crisis just ordinary criminals after all?

Disobedience between disciplines

Even in the history of modern democracies, we encounter situations where such an equation intuitively fails to convince. The liberal American legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin, for instance, looked back on the recent history of the United States during a lecture he delivered in Germany in 1983. In hindsight, Dworkin noticed, a significant portion of Americans were glad about the civil disobedience against the Vietnam War. Likewise, almost no one today would categorize the civil disobedience of the US civil rights movement or women fighting for equal rights as ordinary criminal activity.

So, it’s not surprising that political theory has been dealing with the question of when civil disobedience can be legitimate for a while now. John Rawls, for instance, argues that if there is a serious violation of fundamental principles of justice, civil disobedience may be justified when other institutional avenues to address the injustice have been exhausted while still keeping the stability of the overall system in mind. And in 1983, Jürgen Habermas argued that the idea of a “non-institutionalized distrust towards itself” is integral to the democratic constitutional state. Even in a constitutional state, legal regulations can prove to be illegitimate if they run counter to the moral principles of the modern constitutional state. However, such situations cannot be recognized by the state institutions themselves. It is often the weak and marginalized, the “downtrodden and oppressed,” without privileged avenues of influence, who first experience errors and injustices. “For these reasons as well,” Habermas noted, “the plebiscitary pressure of civil disobedience is often the last chance to correct errors in the process of the realization of a legal order or to set innovations in motion”.

Yet, as compelling as these observations may be, they do not immediately translate into practical and legal implications. “There is no Habermas-compliant interpretation of the German constitution,” writes constitutional law scholar Klaus Ferdinand Gärditz in this volume, emphasizing that even sharp conflicts should be resolved according to the rules of the German constitution. Gärditz is not alone in making this observation. In the 1980s, German legal scholars already extensively examined civil disobedience (before shelving the topic for almost four decades). At that time, the majority viewed civil disobedience as an alien concept that should not be integrated into the democratic or doctrinal vocabulary of legal scholarship. Since the constitution comprehensively regulates the institutions and processes of political decision-making, only the positively established majority will and the checks and balances that we have democratically agreed upon count. In other words: There is no room for selective legal disobedience. However, others were more open to the idea of opening up legal scholarship to certain assumptions of political theory. Although breaking the law should not be simply legalized, the democratic and civic dimension of civil disobedience could be considered in mitigating the punishment, at least in terms of sentencing. This is because those who engage in civil disobedience do so not out of pure selfishness or economic self-interest but symbolically, driven by moral motives, as critical democrats.

Back in the Spotlight

Both of these positions continue to resonate in today’s legal debates on the climate movement. Sometimes they are nuanced, or – as recently – they are being rethought in groundbreaking ways. In any case, there is no doubt that the spectre of civil disobedience is back in the spotlight of legal scholarship.

The great interest in civil disobedience extends far beyond academic discourses. Investigations and legal proceedings, as well as blog posts and public statements from legal scholars, are followed and commented upon beyond legal circles. The intensity and breadth of the debate should come as no surprise. On one hand, civil disobedience has become a political factor in the Federal Republic (again) within a very short time due to the well-coordinated actions of the climate movement, “Last Generation.” This has created uncertainty but also raised legitimate questions. The question of whether, how, and whose civil disobedience should influence political decisions must be carefully discussed. The fact that the broader public is also engaging in this discussion is a positive sign for democratic culture. On the other hand, the civil disobedience of the “Last Generation” changes the strategies of disobedience by no longer primarily targeting the state or companies, but by intending to disrupt the daily lives of the general population (to be precise: motorists). Such an indirect approach, where the aim is state action but the disruption of public life is the means, is successful as an attention strategy but simultaneously raises entirely new (political and legal) questions of justification.

About the structure of this book

This book has emerged from a part of the public debates on the legitimacy and legality of civil disobedience in the climate crisis. It gathers texts that were published on the Verfassungsblog between November 2022 and August 2023, responding to various phases and aspects of the debate. From the very beginning of the protests of the “Last Generation,” the Verfassungsblog has been following this topic. Once again, the debates of recent months have highlighted the importance of an interface between academia and the public; numerous articles were widely shared, intensely discussed, and quickly cited in legal literature and judgments.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++

EUROPEAN SOCIETY. A NEW APPROACH TO EUROPE’S PAST AND FUTURE.

Loïc Azoulai (EUI) and Armin von Bogdandy (MPIL) are establishing an interdisciplinary group to explore the concept of European society (https://www.mpil.de/en/pub/research/areas/european-law/european-society.cfm), introduced in the 2009 Lisbon Treaty but still dormant. The project takes a new conceptual approach aimed at understanding, critiquing, and transforming European societies – as we see them enmeshed in ever denser webs of interdependence, but also fraught with ever deeper conflicts and polarizations.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

The articles in this book are not arranged chronologically but are organized around four major themes that have shaped the debate on civil disobedience in our context. In the first part, the book gathers texts that address the relationship between civil disobedience, legitimacy, and legality at a more fundamental level. The second part focuses on the responses of law enforcement authorities, particularly concerning nationwide raids and investigations against members of the “Last Generation” on charges of forming a criminal organization. The texts in the third part examine how the protests of the climate movement impact two core principles of criminal law: self-defense and necessity. While the question of self-defense revolves around whether and within what limits blocked motorists can confront sit-in blockades, three texts delve into a spectacular ruling by the lower court of Flensburg, which deemed trespassing justified due to the escalating climate crisis. In the fourth and final part, we bring together some administrative and comparative law perspectives. In addition to addressing questions related to policing, civil servants, assembly laws, and school laws, two articles that I would like to strongly recommend to the international readership (as we will be publishing them in their English original) consider Australia and the United Kingdom, exploring how these countries are legislating against civil disobedience in the climate crisis.

Many thanks to Keanu Dölle and Evin Dalkilic for their support in completing this book, to Liz Hicks for assisting with the translation of the editorial, and to Friedrich Zillessen for editing the blog versions by Tobias Gafus, Lena Herbers, Thorsten Koch, Katrin Höffler, Stefan König, and Michael Kubiciel.

The Week on Verfassungsblog

… summarised by MAXIMILIAN STEINBEIS:

That it must somehow be possible and permissible not to be bothered about refugees, whatever they are fleeing from, is a conviction that is becoming more and more widespread in Europe in these dark times. Isn’t it nice to be able to point at dictators in Belarus and elsewhere and accuse them of “instrumentalising” migrants. ALEKSANDRA JOLKINA criticises the vagueness and misuse of this term.

When metal hits metal and artistic freedom hits intellectual property, ugly noises occur. Whether and how the European judiciary manages to resolve them in harmony on the occasion of the latest round of the dispute over “pastiches” in copyright law can be read in JANNIS LENNARTZ and VIKTORIA KRAETZIG.

Federal Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock has had a parody account on Twitter banned. This raises questions of fundamental rights, which TOBIAS HINDERKS explores.

How does one prevent the AfD from flooding the pre-political space with state-funded right-wing extremism through its Desiderius Erasmus Foundation without violating the equal opportunities of the parties? The legislator has to solve this riddle, and MANJA HAUSCHILD and VIVIAN KUBE have analysed the as yet unpublished draft bill of the traffic light coalition for us.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++

Call for Application – MPIL Journalist in Residence Fellowship 2024

Apply now for the #MPIL Journalist in Residence Fellowship 2024 (Deadline: 06 October 2023). The Fellowship is geared towards experienced journalists who report and write on legal and constitutional topics, or topics from politics, economy, and research. For a period of three months, it provides a unique space for research-based journalism, exchanges with leading academic experts, and encounters with new fields of research on law. A monthly research grant and desk space at the institute in Heidelberg is offered for the duration of the stay.

For further information click here.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the EU, the debate on a treaty reform is coming to life again. A comprehensive constitutional reform proposal has been drafted in the Committee of Constitutional Affairs of the European Parliament, which is discussed by LUCA LIONELLO: “If adopted, the proposals would profoundly change the nature of the European Union: the latter would stop being an organisation derived by the will of the Member States and arguably move more towards the structure of a federal state.”

In Poland, general elections are less than a month away. If PiS wins, it will probably be the end of Polish democracy. If PiS loses, it will probably be the end of PiS. In a depressing and highly recommended long read, WOJCIECH SADURSKI describes the levers the ruling party has already pulled to prevent this from happening.

Ecuador has decided in a referendum to leave 700 million barrels of oil in the ground. ANDREAS GUTMANN interprets the process as a break with the principle, also prevalent in German natural resource management law, of focusing on the goal of making nature available.

In Australia, notoriously averse to constitutional change, there will be a constitutional referendum of immense historical significance in October. It is about finally giving the indigenous people a voice. HARRY HOBBS describes what this is about and what is at stake if the referendum fails.

This week, our blog symposium on parliamentary decision-making “on its own behalf” focuses first on specific matters such as electoral law (FABIAN MICHL) and the already mentioned law of political foundations (ANTJE NEELEN) and then on the comparative perspective with contributions by AMAL SETHI, TERESA RADATZ as well as CHRISTOPH KONRATH and MARCELO JENNY.

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an email, you can subscribe here.