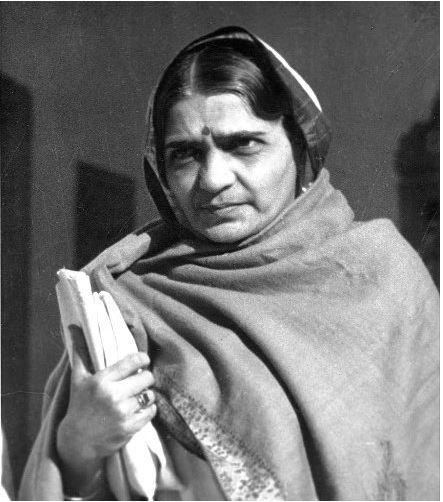

Hansa Mehta

Human Rights with Human Appeal

Imagine if the very first article of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR), 1948, referred to “all men”, rather than “all human beings”, and asked us all to act in the spirit of “brotherhood”.1) Thankfully, that is not how it reads, and for this, credit is due to an Indian woman: Hansa Mehta, whose contribution UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres recognized in his speech celebrating 70 years of the UDHR when he said: “without her, we would literally be speaking of Rights of Man rather than Human Rights.”

The Early Years

Hansa Mehta was born on the 3rd of July 1897, to Manubhai Mehta and his first wife, Harshadagauri.2) She was born in the town of Surat, renowned for its diamond industry, in a high-caste Nagar community – a community known for its contributions to law and literature, and articulate diction. Manubhai was academic-minded, and taught Philosophy at the Baroda College, (later known as the Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda). His second-born daughter, Hansa, would later assume the role of vice-chancellor at this institution, becoming the first female vice-chancellor of any co-educational Indian University. Manubhai himself went on to become the Dewan (equivalent to the Prime Minister) for Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III, the visionary progressive King of the princely state of Baroda (now Gujarat), who is known to have funded B. R. Ambedkar’s education. Following her father’s footsteps, young Hansa studied (and later taught) Philosophy at Baroda College, as well as sociology and journalism at the London School of Economics afterwards: this at a time when less than 2 percent of Indian women got any education at all.3) In England, she met Sarojini Naidu, who would become an influential poet and politician, and to whom Mehta would later dedicate one of her collections of speeches and essays, ‘Indian Woman’.4)

In 1924, the young idealist Hansa married University of London Medal holder medical doctor and fellow idealist Dr. Jivraj Mehta. Jivraj belonged to a caste considered slightly “lower” in social status than the Nagar caste into which Hansa was born. This on the one hand, caused an uproar amongst the Nagars, for which Hansa herself denounced the community, and on the other hand, Maharaja Gaekwad praised her decision in a letter to her father, and also attended all events at her wedding.5) Like his father-in-law, Jivraj Mehta also became the Dewan of Baroda from 1948-49 and was also an elected member of the Constituent Assembly on the ticket of the Congress Party. He went on to become the first Chief Minister of the State of Gujarat, upon the division of the State of Bombay in 1960 on linguistic grounds.

A Gandhian Politician and Women’s Leader

Mehta mentions in her book that she was introduced to Mahatma Gandhi by Sarojini Naidu at Sabarmati Jail in Ahmedabad, and upon meeting him, she was “visibly moved”.6) Her future husband Jivraj was also in London at the same time as Gandhi and they had attended conferences together. In any case, Hansa became an ardent Gandhian – a believer in his principles of satyagraha and ahimsa, that is, the insistence on truth and non-violence, the means through which Gandhi led the Indian independence movement. She, along with her two siblings – older sister Jayashree and her younger brother Kantichandra, became active in the independence movement, picketing on the streets under Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement, which led to her being sent off to jail three times.

Mehta was one of the founding members and the President of the All India Women’s Conference, the oldest national-level women’s organization in India, which played a pivotal role in legislative reforms for the protection of women, including raising the age of marriage for girls. Championing women’s rights and equality, Mehta also drafted the Indian Woman’s Charter of Rights and Duties. The “duties” of women, which included the duty to educate themselves and to care for world peace, were added, unsurprisingly, at the suggestion of Mahatma Gandhi, who knew of this co-authorship between Mehta and Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, who too, like Gandhi, was a resident of Birla House at that time.7)

Drafting the Constitution of India: Mehta’s Vision of Gender Equality

When India introduced the first provincial elections in 1937, upon the passing of the Government of India Act 1935, Hansa Mehta successfully contested for the Bombay legislative council, under the “general” category, refusing to contest under a reserved seat for women. She served on the council from 1937-39 and again from 1940-49. When the Constituent Assembly for the Indian Constitution was set up in 1946, Hansa Mehta was one of the first 11 women who were in the drafting committee of the Indian Constitution, as a representative of the State of Bombay.

Courtesy of Hansa Mehta Library, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda

As a champion of legislative reforms for women, Hansa Mehta further advanced the cause of women’s rights also in the Constituent Assembly Debates. Mehta was also appointed as a member of the fundamental rights subcommittee of the Constitution. Not amused by the distinction between justiciable fundamental rights and non-justiciable Directive Principles of State Policy, which the Indian Constitution has adopted from the Irish Constitution of 1937, she emphasized the fundamental character of the latter.8)

Having contested the election under the general category, Mehta was not only against the affirmative measure of pre-allocated seats for women, but she also strongly opposed a separate electorate for Muslim women, arguing instead for equality between women. Her pride in competing at an equal footing with men, perhaps tilting towards a version of “formal equality”, is reflected in her speech in one of the early sessions of the Constituent Assembly. She said,

“The Indian woman has been reduced to such a state of helplessness that she has become an easy prey of those who wish to exploit the situation. In degrading women, man has degraded himself […] The women’s organisation to which I have the honour to belong has never asked for reserved seats, for quotas, or for separate electorates. What we have asked for is social justice, economic justice, and political justice. We have asked for that equality which can alone be the basis of mutual respect and understanding and without which real co-operation is not possible between man and woman.”9)

To reduce Mehta’s vision of equality to version of formal equality or first wave feminism would be unfair. When India became independent on the 15th of August 1947, minutes after the stroke of the midnight hour, it was Hansa Mehta who, on behalf of women, had presented the first flag of free India to the House, saying that:

“It is in the fitness of things that the first flag that will fly over this august house (of independent India) should be a gift from the women of India. We have […] suffered and sacrificed for the cause of our country’s freedom. May this flag fly high and serve as a light in the gloom that threatens the world today. May it bring happiness to those who live under its protecting care.”10)

Drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Around the same time as the Constituent Assembly, Mehta was appointed to the Human Rights Commission of the United Nations as India’s chief representative, and went on to become its vice-chair. She was one of the two women in the Commission, the other one being Eleanor Roosevelt. Juxtaposed with the stylish Roosevelt, one finds Mehta in her handwoven white Khadi sari, which she wore all her life, for formal meetings often with a brooch.11) In the briefing to Eleanor Roosevelt, Mehta was thus described “as ‘talking in a whisper’, but nevertheless supporting the Indian position tenaciously.”12)

©UN Photo/Marvin Bolotsky

At the Human Rights Commission, where she also chaired the working group on the Implementation of Human Rights Convention, Hansa Mehta insisted that the UDHR should not be aimed at UN member states alone. She adopted a pragmatic view as a response to the deep philosophical debate about the nature of human rights and the priority of the individual, as raised by the Lebanese philosopher Charles Malik. Mehta argued that it was not the place to discuss the perennial chicken-and-egg question of whether the individual comes first, or the society,13) and that the purpose was “to reaffirm the faith in the dignity of the human person”, and not get into the “maze of ideology”.14) On the other hand, highlighting the role of the individual, she said: “The Declaration, which laid down general principles, must be as precise as possible if it was to be understood by the common man”15), thus rejecting both the French draft (for having unnecessary details) and the Chinese draft (for being too terse). She also highlighted that

“the Declaration was not a legal document, but one which would be effective through its moral force and the support of world opinion […]. The Declaration aim[s] at defining the rights of individuals, not the rights of states. It must have human appeal[.]”16)

An Educator Beyond the Law

After independence, the government of India recognized her contribution with the second highest civilian award, Padma Bhushan, in 1959. In her later years, she served on the board of UNESCO, and focused on writing. Her portrait adorns the Hansa Mehta library of the Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad University. Under her vice-chancellorship, the university flourished, producing some leading academics. As the vice-chancellor, she, as an effort to encourage more women to enroll in university education, introduced the faculty of home science at the Maharaja Sayajirao University.17)

Mehta did not only possess a penchant for precision and a strong political mind but also a sense of curiosity, having avid interests such as ornithology and astronomy. Hansa passed on her sense of curiosity and courage to the younger generation in the children’s stories she wrote. She translated Gulliver’s travels as “Golibar ni Musafari” and The Adventures of Pinocchio as “Bavla na Parakramo” as well as other European classics into Gujarati, adapting them to the Indian context. Her other remarkable feat was the translation of the epic Ramayana from Sanskrit to Gujarati in metres, following the original six parts (khanda) in the epic. She went on to live for nearly hundred years, meeting her death in 1995, at the age of ninety-seven.

I would like to thank Mrs Janaki Pankaj Shah, Hansa Mehta’s niece, for sharing her childhood recollections of Mrs Hansa Mehta with the author.

Literary References and Other Sources

- Achyut Chetan, Founding Mothers of the Indian Republic: Gender Politics of the Framing of the Constitution, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Radha Vatsal, Overlooked no more: Hansa Mehta, Who Fought for Women’s Equality in India and Beyond, The New York Times, 31 May 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/31/obituaries/hansa-mehta-overlooked.html

- Hansa Mehta, Indian Woman, Butala & Company, Delhi/Baroda, 1981.

References

| ↑1 | See UN Document E/CN.4/99, 24 May 1948 and E/CN.4/SR.50, 4 June 1948. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Manubhai would later go on to remarry, to Dhanvantagauri, and beget eight more children. |

| ↑3 | Hansa Mehta, Indian Woman, Butala & Company, Delhi/Baroda, 1981, p. 45. |

| ↑4 | Mehta, Indian Woman, p. 45 |

| ↑5 | Mehta, Indian Woman, p. 187. |

| ↑6 | Mehta, Indian Woman, p. 190. |

| ↑7 | Mehta mentions this in the Preface of “Indian Woman”. |

| ↑8 | B. Shiva Rao, The Framing of India’s Constitution: A Study, Indian Institute of Public Administration, 1968, p. 325. Also, Indian Constituent Assembly Debates, vol. 11, 22 November 1949. |

| ↑9 | Indian Constituent Assembly Debates, Vol. 1, 19 December 1946. |

| ↑10 | Hansa Mehta, on the eve of Indian independence, 14 August 1947, available at https://www.constitutionofindia.net/debates/14-aug-1947/. |

| ↑11 | Personal recollection of Mrs Janaki Shah. |

| ↑12 | Documents 1945-50, United States Delegation Handbook No. 2, United Nations Commission on Human Rights, Third Session, Lake Success, New York, May-June 1948. |

| ↑13 | Hegel must have turned in his grave. |

| ↑14 | Human Rights Commission, Verbatim record of the fourteenth meeting, 4 February 1947, Lake Success, UN Document E/CN.4/SR.13. |

| ↑15 | UN Document E/CN.4/SR.50, 4 June 1948. |

| ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑17 | She also dedicates a chapter on the importance of Home Science in her book, Indian Woman. |