Legal “heartfelt thinking”

How “Mingas” Help Evolving the Law

The 2008 Ecuadorian Constitution regards Pacha Mama or Nature as having ‘the right to integral respect for its existence and for the maintenance and regeneration of its life cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes’ (art. 71). A rich body of jurisprudence (here, here and here) has developed around this idea in Ecuador, recognizing today nature’s rights and acknowledging various interpretations of justice and relationships with the natural environment and so-called more-than-human entities (Rodríguez Caguana/Morales Naranjo and García Ruales).

Courts in Ecuador and in many other jurisdictions across the Global South, and increasingly in the Global North (here and here), have addressed this recognition of rights to nature in an heterogeneous and pluralistic manner (Gutmann and Constitutional Court). Yet, it is exactly that cacophony of voices and actors that challenges traditional legal thinking. Rights of Nature (RoN) is an evolving concept that aims at not only opening legal proceedings for more-than-human entities but also for non-hegemonic – such as Indigenous – eco-centric normativities (Gutmann/Morales Naranjo) that refer to ways of normative thinking, or normative practices, that decenter humans as traditional subjects and sources of law and make nature a more central point of reference. Such an opening requires leaving the beaten track and experimenting with new (legal) processes and methods. They can open up a space for experiments that can stimulate legal thinking and contribute to the further development of RoN, as illustrated in the following artistic-legal minga in Quito, organized in the framework of the Amazon of Rights project.

Rights of nature travel the world and the Amazons

The constitutionalisation of RoN in Ecuador has triggered a wave of ‘transplants’ across the planet (Michaels), that is similar to transplanting something from one place to another. This process can be likened to ‘cross-fertilisation’ (Bonilla), a form of horticultural technique, where ideas or legal concepts are exchanged and adapted across different jurisdictions.

More and more legal orders recognize RoN and build on the Ecuadorian case in various ways. RoN pop up in the form of the recognition of legal subjecthood to rivers, fox Run Run, a saltwater lagoon, and waves – even in distant Europe (García Ruales et. al), including more recently in Germany by a local court in Erfurt. This legal migration has generated, as expected, both fascination and irritation (here and here).

Similar to having a tree tomato (Solanum betaceum) grafted with blackberry (Rubus glaucus), Rights of Nature manifest in the Amazons in a diversity of unexpected shapes (for example, see the cases of the Marañón River, the Colombian Amazon or Living Forest (Kawsak Sacha) Declaration (here and here)). RoN include and put at the center more-than-human entities. As such, they are not the only form of eco-centric normativity.

Other expressions of eco-centric normativity in the Amazon include the laws of Indigenous communities, and the norms permanently performed by the region’s countless more-than-human entities, including toucans, seeds, fish, river turtles charapas, trees, spirits, and stones – entities that do not need to be recognized as legal persons to possess agency and influence their surrounding legal landscapes (see also Circovik and García Ruales). Legal makers, intergenerational stories of law, smells and sounds (Parker) all are part of these ‘lawscapes’.

In this sense, and given its planetary relevance, the Amazons is a rich cosmos to explore eco-centric normativities in our Anthropocenic times.

Artistic-legal mingas

These normativities are difficult to capture using conventional legal methods, which is why the artistic-legal mingas are a promising tool. A ‘minga’ is a practice found in various Indigenous cultures in the Andes and the Amazon, particularly among communities in Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru and Colombia. It refers to a communal work effort where members of a community come together to accomplish a specific task or project, such as farming, building infrastructure, organizing events or carrying out political demonstration. Mingas are characterized by cooperation, solidarity, and reciprocity, with community members volunteering their time and labour for the collective benefit of the group and their living spaces. Mingas can also be reflected on the collectively gathering of memories or the collective authoring of new legal interpretations, via the sharing of multiple experiences and projects beyond formal law (García Ruales). This is exactly what took place in the Amazon of Rights’ RoN artistic-legal minga in November 2024 in Quito.

Flyer of the Minga by Cristina Merchán aka Miti Miti

The Amazon of Rights artistic-legal minga brought together poets, musicians, activists, painters, illustrators, comic artists, ancestral judges, rappers, biologists, theater collectives, filmmakers, legal scholars, sociologists and anthropologists – many fulfilling multiple roles simultaneously – to flesh out the various aesthetics and sensory dimensions of rights to nature and eco-centric normativities more generally. As a minga participant in its own right, nature needs to be felt with our own senses and emotions, and most of all, integrated into our daily life. It needs to be corazonada, a word play that mixes corazón (heart) and razón (reason). In our engagement with nature, we should put into practice a type of ‘heartfelt thinking’.

Artistic-legal mingas allow participants to reflect on how eco-centric norms are written but also painted, danced, drawn, performed, sung, woven and corazonados. This is especially pertinent, as Bonilla, Michaels and Zalamea have put it, because ‘the relationship between human beings, law, and nature has also been a primary concern for the arts’, including ‘Inca art and Andean colonial baroque, as well as in modern and contemporary artistic expressions.’

A group of participants in the minga

A much needed eco-centric normativity for planet Earth will be nourished by collective action, strengthened (Fischer-Lescano), claimed, and embodied – corazonada – within the imagination and creativity of collectives, in Quito and beyond. In all kind of contexts, community groups, lawyers and artists (Dietrich et. al) are becoming incubators and guardians of new eco-centric norms and logics. To foster this creative action, future mingas – legal, artistic and otherwise – could be organized, as was ours, following the tradition of popular market (mercados) in Latin America. Following this idea, we organized the Amazon of Rights minga artístico-jurídica through a market stalls format, with larger themes guiding each ‘boot’, including on painting, drawing, collectivity and theater, as well as sounds and textuality (see programme and visual memories here). Below we show how this practice helps evolve and imagine RoN as a new system of law, nourishing them legally, artistically and creatively.

Painting, drawing, collectivity, and theater

Legal RoN cases often struggle with the complexity of nature and the question of how to transfer ecosystemic relationships into the language of a legal proceeding (cf. Gutmann). This issue was addressed by the first boot, ‘Painting with and about Nature’, which began with the intervention of an ancestral Kichwa Indigenous and Andean judge, Alfredo Toaquiza, (see his most recent co-authored book, Apuko). He shared how he learned painting from his father and was trained in Kichwa spirituality from his grandmother. In the strokes of his paintings, he aims to capture the essence Pacha Mama, the right to collectivity of plants, shrubs and trees, Indigenous justice, Andean Amazonian exchanges of power with animals as companions, as well as the disruptive noise of extractivism. Felipe Rodríguez Estévez, Academic Director of the Observatorio de Criminología and Danilo Caicedo, author of the book Viñeta por Viñeta (Vignette by Vignette) reflected on the role of art in conveying messages, discourses, and knowledge. They also called for caution with romanticized and idealized representations of ‘the other’, within the context of eco-centric normativities, including Indigenous peoples and more-than-human entities.

The second boot, ‘Ravines, Rivers and Forests: The Art of Collectivity’, discussed three recent RoN rulings (on Río Monjas with the importance of ravines, the Machángara River – as well traversing Quito – and the Chiquita community located in the province of Esmeraldas). Estefanía Pavón, activist and spokeswoman of Quebradas Vivas (ravines alive), and Lisa María Madera of the Rescate del Río San Pedro Collectives reflected on how these ruling have not only granted rights to different natural entities but also how they have mandated public authorities to develop restoration plans and infrastructure projects. For both speakers, collectives, and the art of community work as such, transform neighbours and associations into guardians of nature and enable them to conceive the essence of nature. For the Chiquita in the documentary Queremos nuestra agua (we want our water), presented by Julie Hazlewood, the art of collectivity continues to denounce river pollution and echoes the voices of birds, mammals, maize (Zea mays), plantains (Musa acuminata), cassava (Manihot esculenta), water, and the spirits of La Tunda and El Riviel, Jeengume and Wualpura—who played a significant role in opposing the palm oil company.

Another way of approaching nature was offered by Sarawi Andrango, Kayambi poet. She was invited to consider how her poetry records a history of resistance by her peoples, the sayings of grandmothers and grandfathers, and the realities of the lands of Kitu Karas. Importantly, according to her, ‘we cannot speak about the Runa (Indigenous Persons), without the Runas’. Finally, we turned to the visual textuality of the documentary, Un viaje épico: la migración de bagre dorado, about the longest migration of catfish (Brachyplatystoma rousseauxii) in the Amazon basin. Ricardo Burgos-Morán, Professor of Biology and conservation researcher who was part of this documentary, explained the importance of corazonar in order to appreciate the natural and spiritual aquatic world of the catfish, which transcends national borders and laws.

Sounds and textuality

It is often argued against RoN that nature itself has no voice and therefore cannot (legally) articulate itself. In response to this, the artistic-legal minga looked for ways to make nature audible. Andrés Galarza Mier, audiovisual artist and creator, opened the boot making us listen to a composition of sonic diversity of Afroecuadorean-rhythms, buffer zones, and Amazonian sounds. Ecuadorian graphic artist, Diana Sofía Zapata Ochoa or Sozapato, spoke about the challenge of illustrating sounds of an Amazonian Forest, for example how to find the sound emitted by stones (mishas). Adriana Rodríguez, Professor of Human Rights at the Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar and expert on linguistic rights, invited the audience to consider opening new debates in the field of RoN, such as on co-authorship in music. Co-authorship developments unfold acknowledging nature’s ways of communication expressed in different rhythms and sounds of each of the natural entities creating a composition, or what scholar Anna Tsing calls a “polyphony”.

Momentarily wrapping up

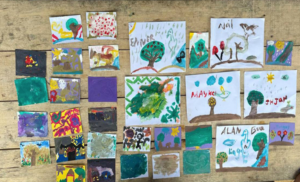

Painted collective memories of the minga

The Amazon of Rights artistic-legal minga concluded with a rap performance in Kichwa and Spanish by Koakali Viteri and Taki Supay, both Kichwa People and members of Sarayaku in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Their intervention brought together the Kawsak Sacha or Living Forest, ‘a living and conscious being, the subject of rights’, and the struggle of members of the Sarayaku People to preserve their culture and surrounding world. Colourful strokes painted by participants in the closing of the minga captured on paper a collective memory of the event. The paintings and brushes used in Quito were then taken to the territory of Sarayaku where children at the Tayak school continue the conversation between Western and Amazonian knowledge.

Paintings at the Tayak school in the territory of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku

Eco-centric normativities and RoN as an expression of them are, as legal scholar Adriana Rodríguez stated in the artistic-legal minga, ‘not a close list – they are always evolving’. They are not only defined by jurisprudential and legal developments, but also in a state of constant construction and creation. As such, we need creative communal practices that can encompass this always evolving nature of rights. Artistic-legal mingas have a remarkable potential to explore ways of relating to nature that are required by RoN and eco-centric normativities more generally. As they offer greater freedom than legal procedures, they open up the opportunity to experiment playfully with new normativities. Following the idea of legal transplants or cross-fertilisation of RoN, we need more of those formats all around the world.