The Rule of Law Stress Test: EU Member States’ Responses to COVID-19

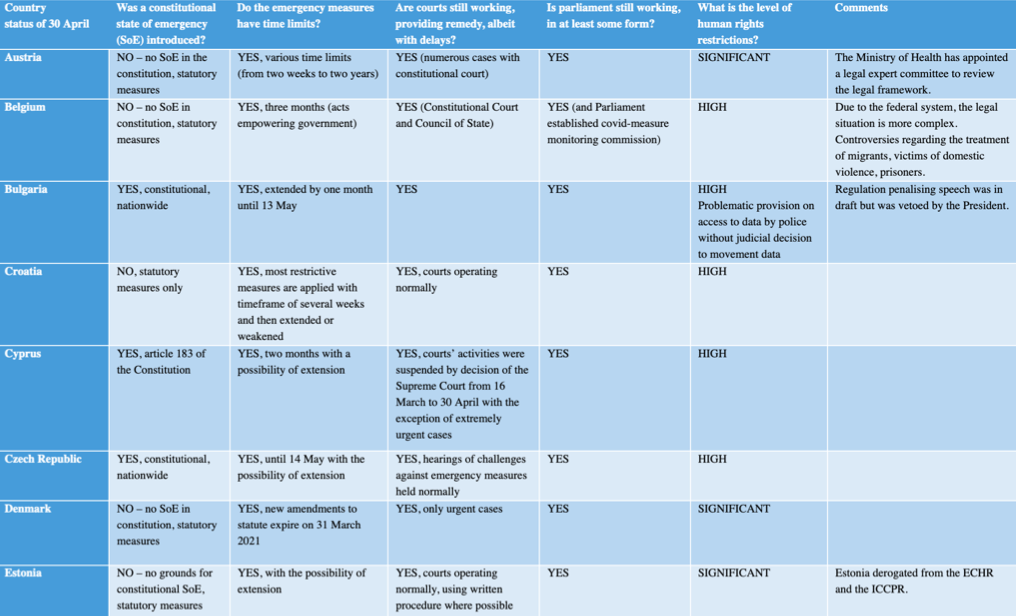

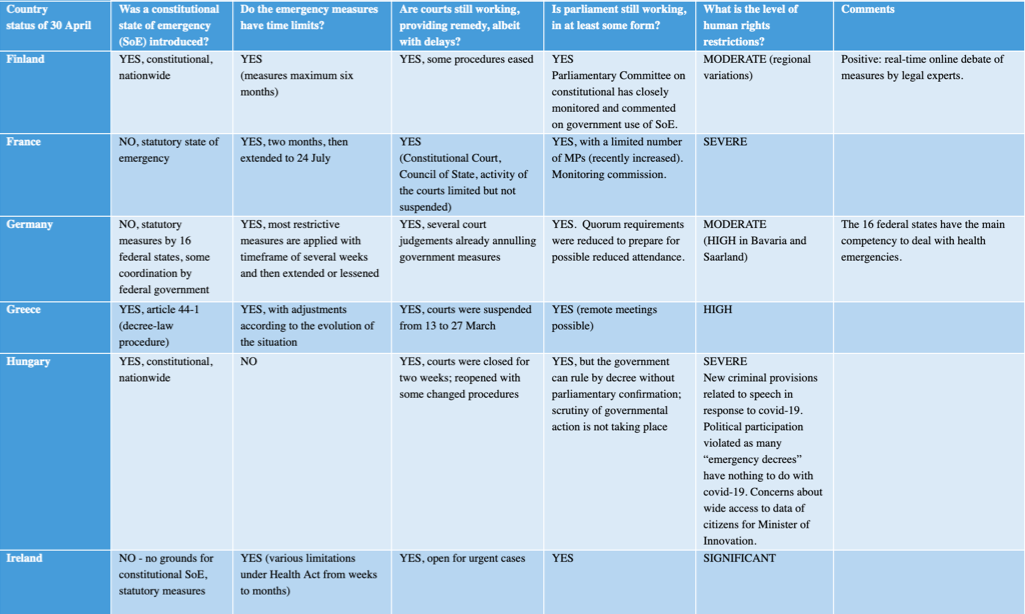

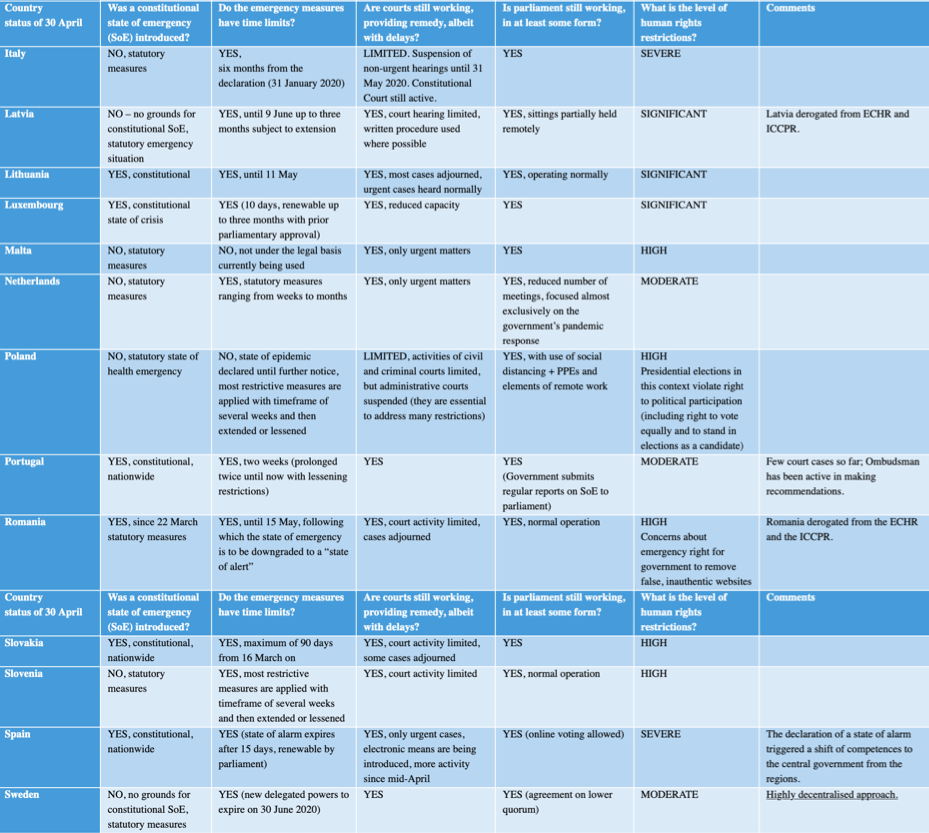

All EU Member States in a State of Emergency

By mid-March, all EU member states were in a state of emergency, whether they officially declared one or not. Across the EU many human rights were severely restricted, particularly the right to free movement. As the table below shows, serious restrictions have been in place across the Union. Even the least restrictive measures – in Sweden – amounted to serious human rights limitations. Several EU member states officially called a state of emergency (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain). ‘States of emergency’ have a bad name because they have often been abused by dictatorships. However, in case of a real threat, such as covid-19, it is not problematic to officially call a state of emergency. It is a possibility foreseen in international human rights law to frame the response to an emergency (for more on this, see DRI’s primer on international law and state of emergency). Not every state of emergency is the same, however. Some exceed what is foreseen in international human rights law. Derogations from human rights should be notified with the relevant bodies of the Council of Europe and the United Nations. Among the EU-27 only Estonia, Latvia and Romania have done so.

Legal Shortcomings of First Responses Were Mostly Corrected Later (Exceptions: Hungary and Poland)

When the World Health Organization (WHO) declared covid-19 to be a “public health emergency of international concern” on 31 January, only Italy reacted. It was not until a few weeks later that most other EU member states suddenly jumped into action and – in the rush – passed measures that were legally questionable. Responses that should have been dealt with in laws were addressed by government decrees or decisions of administrations. The constitutional and legal bases for measures were often unclear or absent. However, after a few weeks – by the end of March – almost all member states corrected early problems through legal amendments (for example Bulgaria, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal). Nevertheless, it appears that many constitutions would benefit from having stronger legal bases for such emergencies.

The government of Hungary made the legal arrangements worse over time. While the initial emergency response in Hungary was limited to a 14-day period, Parliament then passed a law that allows the government to suspend existing laws, adjust their implementation and – the only country in the EU to do so – adopted new legislation that criminalises speech about the pandemic. Statements that may distort the truth and spread panic can now be punished with prison sentences of up to three years. Since then, the Hungarian government has passed numerous emergency decrees, many of them with no connection to covid-19 (building of a museum district, forbidding sex changes), with no involvement of Parliament. Instead of holding the government accountable, the ruling party in Parliament has been busy with issues like refusing to ratify the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention on Violence against Women.

The Polish government avoided applying an obvious constitutional provision on natural disasters because the legal consequence would have been a postponement of presidential elections until 90 days after the end of the extraordinary measures. Judging that the incumbent president, a close ally of the ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, could win, the government created new legislation as a basis for the pandemic response to avoid postponing the election.

The government planned to hold the elections by postal ballot on 10 May despite reservations by the election commission and Europe’s official election watchdog, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). On 6 May it changed course and postponed the election. A new date is not known at the time of writing.

While political rights, such as the right to vote, should be maintained as much as possible during an emergency, in this case the government objectives were of a partisan nature and the vote was held against the wishes of the opposition. The fact that the government appointed a PiS stalwart as the head of the Postal Service’s management board, responsible for administrating the voting by mail, did nothing to allay the fears of a partisan process. The Polish vote cannot be compared to France’s first round of municipal elections in March, which the government held in accordance with the wishes of most of the opposition, which were doing well in opinion polls in contrast to the governing En Marche party. The vote did not represent a government power play, but rather fair play towards the opposition. All French parties then agreed that the second round should be postponed during the pandemic.

The Risks of Corruption

The emergency has resulted in the empowerment of governments to quickly spend significant funds, be it for medical equipment or investments to support the economy, at very short notice. Such a situation increases the risks of corruption. Here, as with all emergency measures, the question is whether rules were abolished unnecessarily or ignored, or whether established and accepted ways of rapid procurement were chosen. For example, the European Commission clarified how European procurement rules allow rapid procurement – even within hours – in cases of “extreme urgency”. Here, as in all other aspects of state of emergency measures, it is important that such rules are not abused for corruption and that they do not stretch beyond the time of their necessity.

Sometimes emergency measures significantly increase risks of corruption when public procurement rules can be circumvented or when they are ignored. Serious concerns were raised in particular around the high-pressure purchase of protective equipment in late March across Europe.

The concern is marked in three EU countries that figure particularly low down on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index, namely Bulgaria (position 74 of 180 countries), Hungary and Romania (both at 70th place). In Romania, a woman with a previous criminal conviction, who had served under current Prime Minister Ludovic Orban in the Bucharest City Administration and in the Ministry of Transport when he headed it, bought stakes in a dormant company on 11 March and won a non-competitive government contract, selling the government on 19 March protective gear which she had purchased the day before for €614,000 from a Turkish supplier. According to reports half of the masks were faulty.

In Hungary, the government suddenly replaced the board of a publicly-traded company that produces cardboard packages for medical products. Some of the new board members have close ties to the ruling Fidesz party. No reasons were given.

It is important that checks and balances continue to function. In Italy, in late April, the authorities arrested three local representatives accused of corruption in the procurement of cleaning-service tenders. Rapid procurement procedures might be a solution, but it cannot be done at the expense of transparency and accountability.

Too Many Laws – A Problem of Legal Certainty

In many EU member states a plethora of legal acts were published which weakened legal certainty – making it harder for the administration, judges, attorneys and the wider public to understand which rules would apply when. Often, there was a lack of coherence to clarify which body was competent to enact measures and on which legal basis. Such lack of clarity undermines accountability and makes it more difficult for anyone seeking a remedy against a measure. In France, the Minister of the Interior announced that the population risked fines for not respecting the confinement 24 hours before the fines were established. In Italy, the Minister of Health declared extensions to freedom of movement, although this was within the Prime Minister’s competence.

Emergency Communication

Proper government communication is essential to avoid confusion in a crisis. It is also essential because democracy does not stop in an emergency. The public has a right to be informed and to have a basis for an informed public debate. While it is understandable that in the early days of the pandemic governments were mostly occupied with addressing the immediate urgencies, the longer this crisis takes, the better public communication should be to ensure democratic debate and accountability. Indeed, the expectations of government communication must be very high in a context of significant human rights restrictions.

Many member states fell short of that obligation to inform. For example, while the German Federal Government has published a lot of important information on covid-19, it never published a written explanation of its overall plan (which objectives, which indicators) to deal with this crisis. While it is true that the 16 states of Germany have the primary role in addressing the situation, the Federal Government has played an important coordinating role. In Slovenia, a journalist who filed an information request on the government’s measures was targeted in a smear campaign by media close to the government. More positively, the Swedish government explains prominently on its homepage what it hopes to achieve through its measures.

Likewise, many member states have made too little effort to translate complex legal arrangements, such as emergency decrees, into simple and understandable guidance to its citizens. It is a rule of law problem if extreme restrictions of human rights are not clearly and easily communicated to the public. In France, the official journal website stopped summarising newly adopted legislation after the beginning of the crisis, something it had previously done on a daily basis. In Italy, the website of the civil protection – the organ in charge of crisis management – gathers the legal measures but without further explanation on their content which makes it difficult for a non-specialist audience to understand.

On the positive side, the Irish government has published an easy-to-understand overview of the next steps in the government’s plan and what citizens should or should not do. A non-EU country, Iceland, also provides a good example of timely, accessible and easy-to-understand information on what is not allowed in the current situation.

Finally, a facts-based public debate has been hampered by a lack of timely and accessible information on essential infection data, such as the number of infections, the number of fatalities and the number of tests administered, ideally all broken down by region. Given that governments have severely restricted human rights to address the crisis, they have an obligation to provide detailed data to justify these measures. It is problematic for example that German media must rely mainly on data from the Johns Hopkins University, because the official case reporting system lags behind by several days. Almost no EU member state provides reliable data on the number of tests administered. Once again, Iceland, provides an excellent example of how to present clear and detailed public information on essential health data.

Many Constitutions Not Fit for Emergency Purpose

In most EU member states many of the early emergency measures were controversial with the legal community, especially for the points raised above: a plethora of acts with no clear hierarchy and order, significant restrictions by decree or administrative decision, reduced roles for parliaments and courts. It became clear that many EU member states do not have a sufficiently clear legal basis in their constitution. While national constitutional and other high courts as well as European courts will pass their final verdicts on many of these measures, it seems clear that in many countries a review of the constitutional basis for emergencies would be useful, so that the legal system is better prepared next time.

Overview of Country Measures

The table below provides an overview of the situation in each EU state. In addition, we examine the level of human rights restrictions in each country.

Human rights restriction levels:

- Moderate – having some impact on everyday life (increased health security on borders, cancellation of large mass events, caution advised for individuals and businesses), serious impact on some (like risk groups);

- Significant – having some impact on everyday life (borders partially closed, limits on size of assemblies, shutting down some non-essential businesses, schools closed for short periods);

- High – considerable impact on everyday life (borders closed for most traffic, personal movement significantly limited, no assemblies, most businesses restricted or closed, schools closed until further notice);

- Severe – overwhelming impact on everyday life (personal movement banned/needs authorisation, borders fully closed, no assemblies, all but essential businesses shut down, schools closed).

The data in this table were gathered from public sources and analytical articles by DRI’s legal experts. Open questions were verified with country experts. DRI also supported an online symposium hosted by Verfassungsblog, which contains detailed analysis of state of emergency measures across the EU and beyond.

(The table was created with contributions by Théo Fournier. You can download the table here.)

This text was first published at Democracy Reporting International.