The Tyranny of Values or the Tyranny of One-Party States?

In his contribution ‘Fundamentals on Defending European Values,’ Armin von Bogdandy counsels caution. The Treaty on European Union may have included legally operative fundamental principles that are the ‘true foundations of the common European house,’ but enforcing these principles strictly could bring the house down. Von Bogdandy darkly recalls Carl Schmitt’s warning about a ‘tyranny of values’ which, he reminds us, is ‘a defense of values which destroys the very values it aims to protect.’

As von Bogdandy argues, there are important values on the other side. Under Article 4(2) TEU, the EU must respect domestic democracy and constitutional identity – and this commitment requires the EU to tolerate normative pluralism. Moreover, the EU has always stood for peace, and attempting to enforce a common set of values too strongly at a delicate moment may lead to explosive conflict. While von Bogdandy recognizes that EU cannot exist without a common foundation of values and he acknowledges that Article 7 TEU is a cumbersome mechanism for enforcement of those values that requires supplementation, the thought of the EU pressing a Member State to conform to EU values when it is determined to head in a different direction nonetheless makes him queasy.

Von Bogdandy’s arguments are wise in normal times. The EU has long looked the other way while Member States have engaged in normative freelancing, and the EU has previously been rewarded when these states (France under de Gaulle and Italy under Berlusconi, for example) have returned to the European fold through the normal democratic rotation of power. But we no longer live in normal times. The current governments of at least two Member States, Hungary and Poland, are engaged in normative freelancing with the explicit aim of making future democratic rotation impossible, so the self-correction mechanisms on which previous ‘normal times’ have relied will no longer work. Moreover, these rogue governments are not taking their citizens out of the normative embrace of the European Union because their citizens have demanded that these governments do so. The rogue governments we see today are undermining the values of the European Union when the EU is more popular in these Member States than their own governments are.

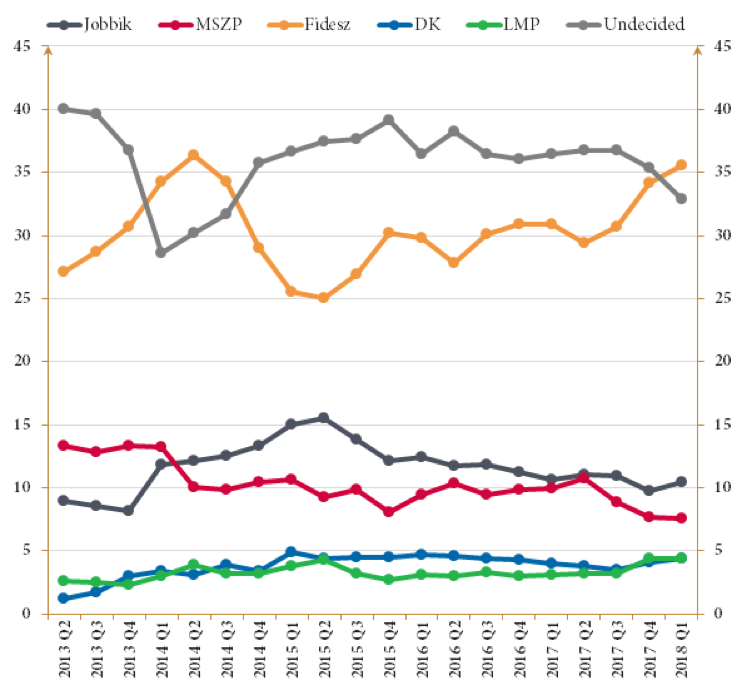

Take Hungary, which is no longer a democratic state because its citizens can no longer change the government when they so desire. In 2010, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz party came to power with an absolute majority of the votes in a free and fair election, but due to the inherited disproportionate election system, the 53% of the vote gained by Fidesz turned into 67% of the parliamentary seats. Under the Hungarian constitution that Orbán also inherited, a single two-thirds vote in the unicameral parliament could change the constitution as well as the so-called “two-thirds laws” that governed important aspects of Hungary’s basic governmental structure and human rights. Orbán’s constitutional majority allowed him to govern without legal constraint, and he won this constitutional majority again in 2014 and 2018. But while Orbán has maintained two-thirds of the parliamentary seats for nearly a decade, he has never had anywhere close to two-thirds of the public behind him. Instead, his party generally hovers at around one-third popular support. What is perhaps most shocking is that there are usually even more people who do not support any of the existing political parties.1)

So how does Orbán win such overwhelming victories in Hungarian elections? Through election law tricks. In December 2011, the Parliament enacted a controversial election law that gerrymandered all-new electoral districts. In 2013, another new election law made the electoral system even more disproportionate, by increasing the proportion of single-member constituency mandates and eliminating the second round run-off in these constituencies so that the seats could be won by much less than a majority vote. The law also introduced ‘winner-compensation,’ which favored the governing party in the tallying of party list votes and managed to suppress the vote of ex-pats who had left under pressures from Orbán’s tightening control while allowing in the votes of new citizens in the neighboring states who backed Orbán.2) With this rigged electoral system Fidesz was able to renew its two-thirds majority both in 2014 and 2018 with less than a majority of the popular vote.

The OSCE election observers were very critical of both the 2014 and 2018 elections, noting that “overlap between state and ruling party resources,” as well as opaque campaign finance, media bias, and “intimidating and xenophobic rhetoric” also hampered voters’ ability to make informed choices. A study of the rural population in Hungary in the 2014 election found that the government used the threat of withdrawal of public employment to leverage votes for Fidesz. Research done in conjunction with the 2018 election found numerous irregularities, including busloads of voters brought in from neighboring countries to vote in Hungary as well as widespread vote buying and intimidation. The election office computer crashed on the night of the 2018 election and numerous election officials reported irregularities in the registering of their election logs. In both 2014 and 2018, Orbán got just exactly the number of seats he needed to keep his two-thirds majority, needing every trick he played. While it’s true that Orbán Fidesz party has remained more popular than any other single party and Fidesz would have “won” the election in any event, Orbán would never have gotten his consistent two-thirds majorities without rigging the election laws.

Beyond rigging the electoral law, Fidesz made the playing field even more uneven by dismantling independent media and threatening civil society. Whenever an opposition party starts to show that it might challenge Orbán, it is ridiculed in the Fidesz-controlled media, investigated by the Fidesz-controlled State Audit Office (and often fined), and harassed by the Fidesz-controlled Election Commission. Without the ability to gain attention through independent media or to find a base in civil society, it is hard for any coherent opposition to form in the first place. As Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way have argued: “Clearly, Hungary is not a democracy… Orbán’s Hungary is a prime example of a competitive autocracy with an uneven playing field.”

Rousseau may have inspired Carl Schmitt’s concept of democracy, but the mysterious ‘general will’ is now used by autocratic nationalists like Viktor Orbán to build an ‘illiberal democracy’ that he claims Hungarians support. Illiberalism is highly critical towards all democratic values, including those currently enshired in Article 2 TEU as well as in Article 4(2) TEU. Orbán’s isn’t merely illiberal in not respecting human dignity, minorities’ and individual’s rights, the rule of law and separation of powers, but he isn’t democratic either, because the outcome of the elections are foreordained.

Orbán’s Hungary isn’t only a ‘pseudo-democracy,’ but it also abuses the concept of national identity protected in Article 4(2) TEU. From the very beginning, the government of Viktor Orbán has justified non-compliance with the values enshrined in Article 2 TEU by referring to national sovereignty. Nowhere has this been clearer than when the government refused to accept refugees in the giant migration of 2015, and also refused to cooperate with the European relocation plan for refugees after that. After a failed referendum in which the Hungarian public refused to support the Orbán government in sufficient numbers as it sought a public rubber-stamp for its rejection of refugees, the packed Constitutional Court came to the rescue of Hungary’s policies on migration by asserting that they were part of the country’s constitutional identity.

The Constitutional Court in its decision held that ‘the constitutional self-identity of Hungary is a fundamental value not created by the Fundamental Law – it is merely acknowledged by the Fundamental Law, consequently constitutional identity cannot be waived by way of an international treaty’.3) Therefore, the Court argued, ‘the protection of the constitutional identity shall remain the duty of the Constitutional Court as long as Hungary is a sovereign State’.4) This abuse of constitutional identity was aimed at rejecting the joint European solution to the refugee crisis and clearly flouted common European values, such as solidarity.

In a more recent decision, the Constitutional Court by ruling that the criminalization of ’facilitating illegal immigration’ does not violate the Fundamental Law again refered to the constitutional requirement to protect Hungary’s sovereignty and constitutional identity to justify this clear violation of freedom of association and freedom of expression hiding behind the alleged obligation to protect Schengen borders against ’masses entering [the EU] uncontrollably and illegitimately.’ (for more detail see here). The Commission has brought several infringement actions against Hungary for its handling of asylum claims and for its mistreatment of claimants, but the Hungarian government rejects all “interference” from Brussels on this point.

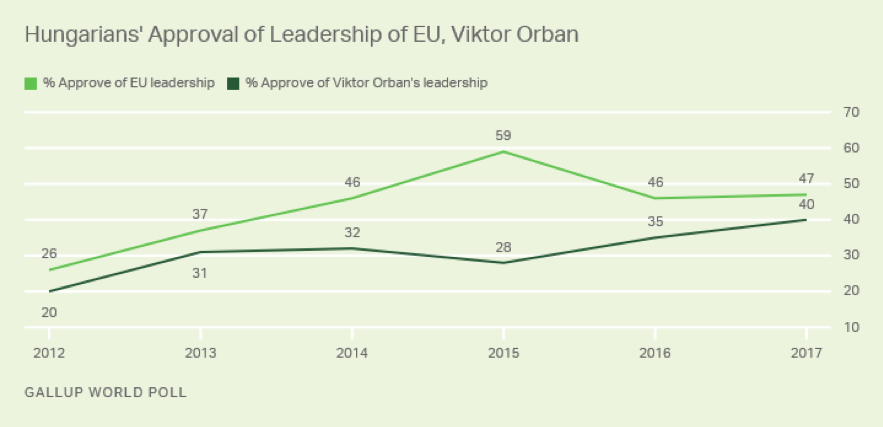

The irony of Orbán’s rejection of the common asylum policy in particular and European solidarity in general is that, when migration was at its height, more than twice as many Hungarians approved of the EU’s leadership at the time as approved of Viktor Orbán’s. As the results of the Gallup Poll indicate, below, in the summer of 2015, at the height of the migration crisis, when Viktor Orbán was defending Hungarians from international “invasion” while the EU was encouraging Hungary to process the asylum claims of a mere 1293 refugees, the popularity of the EU soared, while the popularity of the Hungarian government fell:

And this was not a fluke. On the more general question of approval of the EU (and not just of its leadership as in the prior question), Hungarians outdo all but one other Member States in having a favorable view of the EU. In spring 2016, the first time that the Pew Research Center surveyed Hungary after the migration crisis reached its peak, only Poland surpassed the Hungarian public in its approval of the EU. Evidently, the hard line that Europe had taken on migration did not provide a reason for Hungarians, even if it provided a reason for Orbán, to abandon European values.

As we have seen, then, the Constitutional Court’s argument that national identity requires closing the doors to Europe are not shared by the Hungarian population. And if a national population doesn’t believe its state institutions’ assertions of national identity against the core values of the European Union, what respect does this national identity deserve?

The respect for a Member State’s national identity – with its political structures reflecting a commitment to democracy and its constitutional structures representing the national values of the country – must depend ultimately on whether the citizens of that state are willing to defend that national identity. But with this survey of the Hungarian government’s (lack of) commitment to democratic governance and the Hungarian public’s strong commitment to Europe, we can have a very different view of the cross-pressures brought to bear on the European Union from Article 4(2) TEU. Since there is neither democracy nor genuine constitutional identity to respect in Hungary, given the way that both have been abused by the Orbán government, the EU is more than justified in intervening to interrupt the tyranny of a one-party state.

In our present moment, the citizens of the most visible rogue state in the EU are not like passengers who voluntarily bought a ticket to an illiberal destination and are demanding to be taken there. If they were, then the democratic systems these citizens have relied on to voice their preferences and the constitutional commitments that these citizens have crafted might qualify as a genuine national identity under Article 4(2) TEU. But when Member States full of European Union citizens are being hijacked by their own governments to go to a non-European destination that they never sought to visit, however, the Union’s commitments to national democracy and national identity should lead it to intervene. In doing so, the Union would be defending both EU principles as well as the importance of domestic democracy and national identity. Article 4(2) and Article 2 are not in conflict when we consider rogue Member States that have closed their national democratic space.

We understand that von Bogdandy is justifiably nervous about the EU overriding its Member States on matters of constitutional identity. But as we have tried to show here, these are not normal times, nor are these normal and responsible claims of constitutional identity. The values of Article 2 TEU were placed in the legally operative part of the Treaty on European Union because they must be guaranteed in order for the European Union to function. If democracy is hijacked, courts are captured, rights are threatened and the EU is disrespected by a Member State government, the sincere cooperation guaranteed in Article 4(3) cannot be guaranteed. It will surely be both difficult and unpleasant for the EU to try to enforce its values. But the rule of law crisis requires difficult and determined action to prevent the foundations of European law from weakening to the point where the common home that Europeans share collapses.

References

| ↑1 | In considering survey data out of Hungary, it is important to ask what the survey researcher has done with the “don’t knows” on the question pertaining to support for the government. Not surprisingly, Fidesz generally omits the “don’t knows” and reports their support among “decided” voters, where its numbers are much higher. But having such large fractions of voters refuse to align with any party is a sign of democratic deficiency all by itself and worthy of reporting. In the population as a whole, supporters of Fidesz rarely top 40% and instead hover around 35%. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For details of the voting rules that applied first in the 2014 election and were kept largely the same for the 2018 election, see Kim Lane Scheppele, Hungary: An Election in Question, Part 1: The Political Landscape (NY Times, Feb 28, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/NB4R-UMWQ (laying out the distribution of political forces that were the object of gaming in the election rules); Kim Lane Scheppele, Hungary, an Election in Question, Part 2: Writing the Rules to Win—the Basic Structure (NY Times, Feb 28, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/95M5-6573 (showing how a combination of gerrymandering and new rules awarding parliamentary seats tilted the election in the governing party’s favor); Kim Lane Scheppele, Hungary, an Election in Question, Part 3: Compensating the Winners (NY Times, Feb 28, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/U39T-9VMP (showing how the majority party turned its margin of victory into a supermajority result and interfered with the independence of the Election Commission); Kim Lane Scheppele, Hungary, An Election in Question, Part 4: The New Electorate (in Which Some Are More Equal than Others) (NY Times, Feb 28, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/69HC-4XJ5 (showing how nearly half a million voters were disenfranchised and a different half million new voters were added to the voter rolls, while a clever system to divert minority votes to ethnic lists was designed to ensure that ethnic minorities would never gain any parliamentary seats); Kim Lane Scheppele, Hungary, An Election in Question, Part 5: The Unequal Campaign (NY Times, Feb 28, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/63D5-9MST (showing how the campaign rules and the election authorities themselves benefited the governing party). |

| ↑3 | Decision 22/2016 AB of the Constitutional Court of Hungary, para [68]. For a detailed analysis of the decision, see Gábor Halmai, Abuse of Constitutional Identity. The Hungarian Constitutional Court on Interpretation of Article E) (2) of the Fundamental Law, 43 Review of Central and East European Law 23-42 (2018). |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |