Art. 21 DSA Has Come to Life

Art. 21 DSA is a new, unusual and interesting framework to settle disputes over online content moderation decisions. It might be described as a “new animal”, introducing alternatives to existing redress mechanisms.

By now, the first four online dispute settlement bodies (ODS-bodies) have been certified, and most of them have already started taking cases. In this article, based on recent interviews with representatives from all certified bodies, I will explore how these very first ODS-bodies are set up and which very first experiences they have made.

As I will show, Art. 21 DSA is seemingly delivering a good start. The Digital Services Coordinators in Malta, Germany, Hungary, and Ireland have certified, in my impression, bodies that are ‘serious’, who are diligently starting processes, and that offer Union citizens a low-threshold access to independent review of the platforms’ content moderation decisions. That is pretty big news. However, the more successfully ODS-bodies are becoming, cases mounting easily in the hundreds of thousands in the years to come, the more we should watch out for potential systematic flaws of the new framework.

How the “new animals” do

As of today, four ODS-bodies have been certified by Digital Services Coordinators (DSCs): Online Platform Dispute Resolution Board (OPDRB) (certified in Hungary), ADROIT (Malta), User Rights (Germany) and Appeals Centre Europe (ACE) (Ireland).

1. Actors and backgrounds

All four bodies are run by legal persons, giving the impression of serious actors, carefully setting up processes, concerned about delivering transparency and just outcomes.

The initiative for the Hungarian OPDRB came from Hungary’s national media authority asking media companies to suggest experts, who have then set up the body. It seems that OPDRB is a rather specific actor, which, through requiring a nominal fee and restricting itself to Hungarian language content, is not aiming at processing large numbers of cases from the whole Union.

ADROIT and User Rights instead might aim at high numbers of cases. They do not require applicants to pay a nominal fee, making proceedings basically cost-free for applicants. Both entities are run by lawyers, bringing experience from other areas of dispute settlement (ADROIT), content moderation and Legal Tech (User Rights).

Appeals Centre Europe (ACE) is a Meta Oversight Board spin-off: Its founding members come from there and they start with a U.S. $ 15 Mio grant from the Oversight Board. However, ACE is aiming at loosening ties by incorporating a majority of new members from outside the Oversight Board. Long term funding shall rely solely on Art. 21 DSA fees.

2. Certification and oversight

Not so much is known about the certification processes. But it seems that DSCs have been acting fast, thus helping to make Art. 21 DSA an early success. The Irish as well as the German DSC have published guidelines (here and here), which, however, do not add much flesh to the details of Art. 21 DSA (see here and here).

Some DSCs seem to allow greater flexibility towards ODS-bodies’ needs. E.g., some DSCs might allow modifications of the bodies’ rules of procedure even after certification; and the Irish DSC seems to be ok with ACE not being immediately operational.

It remains to be seen how DSCs will conduct oversight in the future, especially when it comes to reviewing ODS-bodies’ decision making. In my view, when deciding on renewal or revocations of certifications, DSCs will need to evaluate the expertise and independence of ODS-bodies, which then will require reviewing whether policies and laws have been applied correctly. I have asked respective questions to the Irish as well as the German DSC: While it seems that they do not plan with regular review of decisions, they responded that on a case-by-case basis, as part of regulatory oversight proceedings, e.g. for the question of revocation under Art. 21(7) DSA, investigations might include such a review of ODS – decisions.

3. Working areas

ODS-bodies are free to seek limited certification. E.g., Hungarian OPDRP’s certification is limited to Hungarian language content. ADROIT seems able to take all kinds of cases, though aiming at commercial contexts (e.g. online marketplaces). User Rights is currently only taking cases regarding Instagram, TikTok und LinkedIn and they focus on defamation and hate speech cases, leaving aside IP- and CSAM-disputes. ACE’s certification is not limited to certain platforms, but they initially restrict themselves to Facebook, TikTok and YouTube. Interestingly, they only plan taking cases based on platforms’ content policies decisions.

4. Decision makers

Most ODS-bodies constitute a set-up where decision makers operate separated from managing functions. For these decision makers, ODS-bodies mostly seem to rely on fully qualified lawyers. User Rights is showing more flexibility for cases only requiring application of platform policies (senior law students eligible when bringing respective work experience). ACE is currently recruiting and training a core expert team of 5 – 10 decision makers. OPDRP consists mainly of legal scholars (listed here).

Most ODS-bodies are set up to decide individual cases through single-person decision makers (OPDRP: 3-person panel). ADROIT and User Rights might optionally decide very complex cases through a 3-person-panel.

5. Procedural questions

All bodies have set up rules of procedure (OPDRB, ADROIT, User Rights) or are currently drafting such rules (ACE). Generally, these rules contain provisions governing eligible cases, administrative questions (assignment of cases), deadlines for arguments etc.

Most ODS-bodies do not plan with oral hearings, but OPDRB wants to conduct video-conferences. In an ideal case, bodies aim at being able to decide after a first round of (written, electronically submitted) pleadings. Some ODS-bodies have set explicit rules for judgment by default, when either applicants or platforms fail to produce sufficient context or feedback. Most bodies do not see themselves in a position to take evidence. Rules of procedure sometimes clarify this. According to ODS-bodies feedback, cases are rare in which disputed factual circumstances might be decisive.

Most bodies have established privileged channels of communication with major platforms or are in the process of doing so.

6. Fee structures and cost-bearing

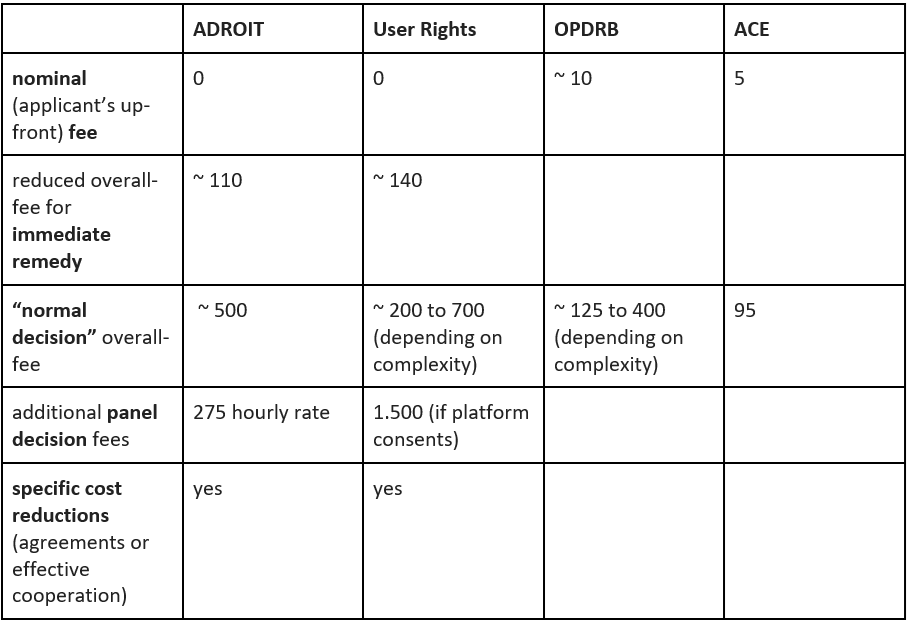

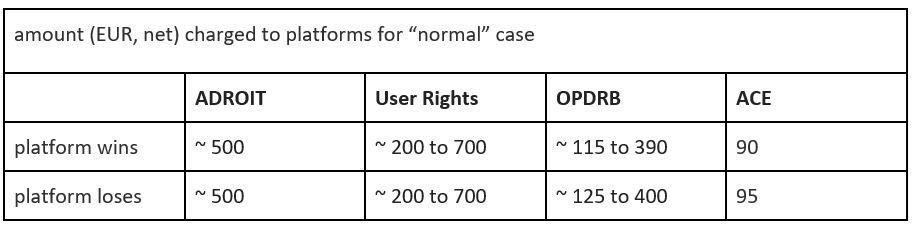

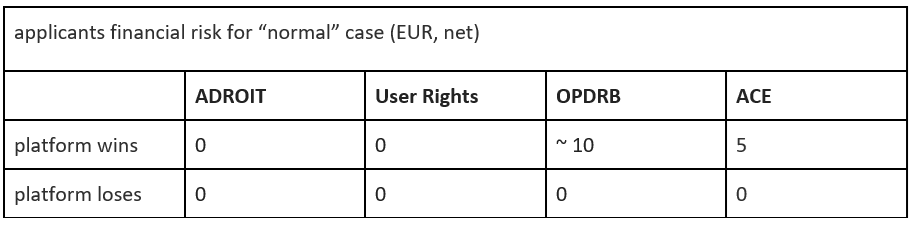

The fees and the cost-bearing mechanic of Art. 21 DSA are the provision’s most disruptive aspect. ODS-bodies will charge overall-fees, which are supposed to cover ODS-bodies’ total costs. ODS-bodies are free to require applicants to pay a little up-front nominal fee. If the applicant wins the case, then this nominal fee is reimbursed to the applicant and the whole overall fee is charged to the platform. If the platform wins the case, then this nominal fee is not reimbursed, and platforms will be charged with overall fees minus the nominal fee. Only ACE (5 Euro) and OPDRB (~ 10 Euro) require such a nominal fee. Only in rare cases of established manifest bad faith applicant action will the applicant have to bear all overall fees.

ODS-bodies overall fees are diverse. ACE is planning with 95 Euro for all proceedings. Other bodies have set up complex structures (see ADROIT – Fee Model, User Rights – Fee Rules), trying to mirror the actual workload of proceedings: E.g., ADROIT and User Rights, through substantial discounts, will reflect diminished workload when platforms immediately reverse moderation decisions (immediate remedy). For “normal” proceedings ending with a decision on the merits, ADROIT sets an overall fee at about 500 Euro (net), User Rights, depending on the complexity of the case, at about 200 to 700 Euro (net), OPDRB between about 125 to 400 Euro.

Additionally, ADROIT and User Rights, for complex or economically relevant cases, reserve the option to decide through 3-person-panels resulting in additional fees.

User Rights, in its Rules of procedure, enables lower fees if platforms engage in fully electronic data transfer through specific API or similar tools. ADROIT is aiming at concluding Mutual Administrative Assistance Agreements (MAAAs) with platforms. In this case, “therein agreed case decision fees” shall apply.

The following table shows a (simplified) overview over fee structures (Euro):

The next table illustrates how platforms, whether they win or lose, will almost always (except rare cases of manifest bad faith applications) bear all or nearly all of ODS-bodies’ costs:

On the other hand, consider the zero/near-zero financial risks for applicants (manifest bad faith actions left aside):

7. Diversity of applicants and cases

As of mid-October, ODS-bodies have already received a substantial number of cases. That is, for ADROIT roughly 1.000, for User Rights roughly 300, and the OPDRP about 15, ACE has not yet taken cases).

So far, applicants come from all kinds of directions (reporters & uploaders, commercial and non-commercial backgrounds). Some bodies signaled to observe applicants who repeatedly initiate proceedings, potentially becoming “regular customers”.

Applicants are bringing diverse cases: Take-down requests alleging product safety laws violations (concerning a competitor’s products on trading platforms), non-licensed use of creative works, Nazi- emblems in multiplayer-games, disputed customer-ratings, app-developers blocked from an app-store, users protesting account suspensions for suspected identity-theft, or account restrictions following hateful postings. Disputes not only involve big social media platforms, but also more niche platforms, like gaming or gambling sites.

8. Platform engagement

Most ODS-bodies found platform engagement, for most parts and with differences between platforms, to look promising. Interestingly, some platforms are pretty often reversing moderation decisions immediately after learning of the ODS – proceeding (immediate remedy), while other platforms would not do so at all. The differences between platforms might mirror different platform policies or varying levels of preparation for Art. 21 DSA.

Maybe different to lawmakers’ intentions, it seems that ODS – proceedings are not used for negotiations or sophisticated techniques of dispute settlement like mediation or similar. As it seems, platforms will either opt for immediate reversal, or otherwise more or less defend their moderation decision and then just wait for the ODS – decision.

9. Decisions

As it seems, all platforms will deliver written reasonings for their decisions. Some bodies, in their decisions, will not reveal the individual name of the decision makers.

In their decisions, ODS-bodies seem to restrict evaluation to the specific platform policy or applicable laws cited by the platform as justification during the moderation process (see Art. 17 DSA). It remains to be seen how to deal with modifications of reasons during the proceedings.

Calculating reversal rates by the outcomes of ODS – decisions would be premature, but a substantial amount of ODS – decisions has found platforms’ decisions to be erroneous. So far, no robust observations could be made about platforms’ willingness to implement ODS – decisions.

Discussion and outlook

As an overall impression, Art. 21 DSA is seemingly delivering a good start. DSCs have certified “good actors”, who are diligently starting processes. Though ODS-bodies have rather silently begun operations, we are already seeing a substantial number of cases. I assume that we might see many more, up to tens of thousands in 2025.

One thing to watch out for in 2025 is how Appeals Centre Europe (ACE) might play a special role within the ecosystem of Art. 21 DSA. Given ACE’s very modest overall fees, it would serve platforms’ interests if recipients bring their cases there instead to other bodies. But platforms have limited options to steer applicants’ decisions where to bring cases. One very hypothetical development could go as follows: If platforms, gaining trust in the work of ACE, would regularly decide to implement ACE’s decisions, applicants could view ACE as a preferred option.

Especially with an expected avalanche of proceedings, in my view, other, more questionable potential consequences of Art. 21 DSA deserve attention: For example, given the extreme one-sidedness of Art. 21 DSA’s cost-bearing scheme, one should question the proportionality of the financial burdens placed upon the platforms. More specifically, the rather high proportion of immediate remedies deserves attention: Through their fee structures, ODS-bodies are “rewarding” platforms for waiving the white flag by immediately reversing their moderation decision. Such monetary discounts might incentivize premature reversals for the sake of avoiding costs. This points to a larger problem inherent to Art. 21 DSA: As recipients can (disproportionately) financially “punish” platforms for moderation decisions, Art. 21 DSA might incentivize “worse” content moderation in the form of “over-put-back” or “under- and overblocking” (for an in-depth discussion of all this critique see Holznagel in: Müller-Terpitz/Köhler, DSA, Art. 21).

Given these uncertainties, it will be interesting how national DSCs are exercising oversight, and how DSCs will report on the functioning of Art. 21 DSA, with a specific view to “systematic … shortcomings”, Art. 21(4)(c) DSA. For this, DSCs might have to review and assess the ODS – decisions, which might turn out to be a challenging regulatory task.

Art. 21 DSA ist ein Schritt in die richtige Richtung. Es wäre wichtig, wo Macht missbraucht wird – sei es durch staatliche oder private Machtträger oder durch Täter, die ihre Gewalt im Schutz anderer ausleben.