Due Diligence Around the World

The Draft Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (Part 1)

On 23 February 2022, the EU Commission released its draft Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence (CSDDD). It follows – and seemingly takes inspiration from – several national mandatory human rights and environmental due diligence (HREDD) laws, notably in France, (“LdV”) Germany (“GSCDDA”) and Norway (“Transparency Act”). It provides a strong legal basis and innovations to enhance corporate accountability, to strengthen stakeholder value and to create a European and possibly global standard for responsible and sustainable business conduct.

More than 1% in fact

The CSDDD, like the LdV and the GSCDDA, applies to large companies. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are generally excluded from their direct scope. Considering that SMEs represent approximately 99% of all companies in the EU, their exclusion is a significant limitation of the CSDDD’s scope. However, the experience of the French LdV shows that nearly 80% of French SMEs – which are not directly subject to the law – are still asked to implement at least some measures of HREDD when they supply to larger companies covered by the LdV. It is therefore clear that the CSDDD too will indirectly apply to a significant number of SMEs that are part of larger companies’ value chains.

Specifically, the CSDDD covers EU companies with more than 500 employees on average and a worldwide net turnover exceeding EUR 150 million in the previous financial year (Art. 2 (1)). Companies in “high impact sectors” – which include textile, agriculture and extraction of minerals (Art. 2 (1)(b)) – will also be covered after a transposition period of two years, when they have more than 250 employees on average, and a net worldwide turnover exceeding EUR 40 million in the previous financial year and if at least 50% of this net turnover is generated in one or more of these high-impact sectors.

With respect to third-country companies, the CSDDD’s scope is broader than that of its German and French counterparts which only apply to companies that are registered or have a branch in the respective countries. The CSDDD, however, also covers companies with “significant operations in the EU”, defined in terms of turnover generated in the EU. This criterion shall create the territorial connection between the third-country companies and the EU territory and justify regulation as required under international law (recital 24). The relevant threshold is a net turnover of at least EUR 150 million in the European Union in the last financial year. After two years, a lower threshold (of a turnover of more than EUR 40 million) will apply if at least 50% of a company’s net worldwide turnover was generated in one or more of the high-impact sectors. Calculating the number of employees worldwide would be difficult which is why the CSDD focuses on the turnover which can be calculated using the method already developed under the Country-by-Country Reporting Directive (recital 24).

Human rights and environment spelt out

Under the CSDDD, companies have to avoid a wide range of adverse human rights and environmental impacts. Their enumeration is similar to the approach taken in the GSCDDA and avoids the problems of the legal ambiguity of Art. 1 LdV which merely states that companies must consider “human rights”, “fundamental freedoms”, and the “environment”. This ambiguity was the reason that the French Constitutional Court struck down the criminal sanction originally envisaged in the LdV.

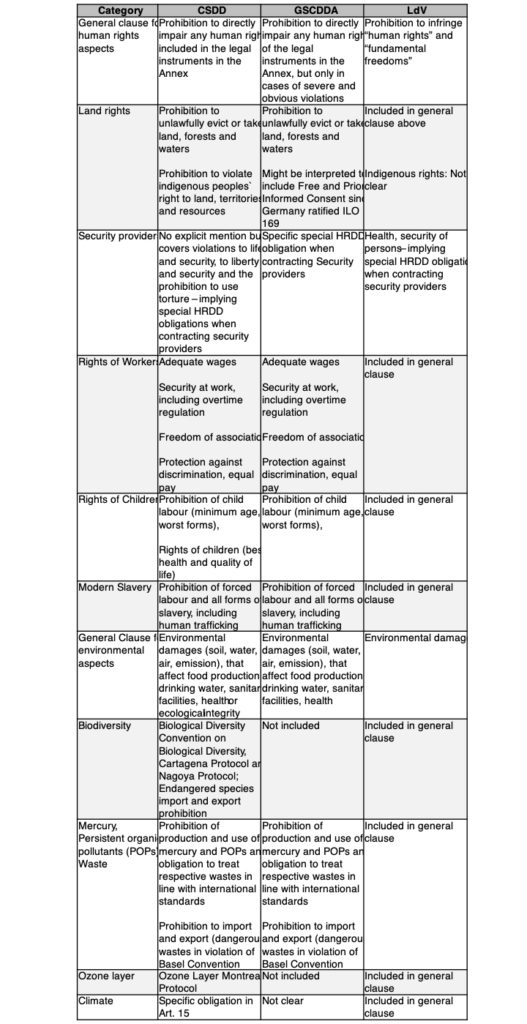

In Art. 4-11, the CSDDD sets out HREDD obligations which all refer to “adverse impacts” that need to be managed. Adverse environmental impacts are defined in Annex II of the CSDDD, and adverse human rights impacts in Annex I.1) The explanatory memorandum does not make reference to the role of decisions of the UN bodies in interpreting the provisions. However, as all CSDDD risk provisions refer to specific Articles of international covenants, it stands to reason those interpretations should be taken into account to interpret the respective terms. The following table summarizes relevant rights and impacts which are included under the CSDDD in comparison to the GSCDDA and the LdV:

Adopting a climate change plan

According to Art. 15 (1) CSDDD, companies must adopt a plan to ensure that their business model and strategy are compatible with “the transition to a sustainable economy” and with the limiting of global warming to 1.5 °C in line with the Paris Agreement. In this plan, companies must identify the extent to which climate change is a risk for or an impact of the companies’ operations. Additionally, companies will have to include specific emissions reduction objectives in their plans, if they identify climate change as a “principal” risk for, or principal impact of their business operations. Art. 15 (3) CSDDD obliges companies to link variable parts of directors’ remuneration to the achievement of this plan. The obligations to create such a climate action are not technically a part of the HREDD procedures. This means that the CSDDD rules in Art. 4-11 on mitigation, prevention of adverse impacts or complaints procedure will not apply to climate risks, as Art. 29 e also clarifies.

HREDD obligations

The CSDDD, like the LdV and the GSCDDA, requires companies to conduct HREDD. Its Art. 4-11 follow established HREDD principles and require companies to put systems into place which identify risks to human rights and the environment and to respond with measures that prevent, mitigate, end or at least minimize them, and to report on them. Moreover, companies must establish and maintain a procedure for complaints by affected persons and evaluate if the HREDD measures are effective. Companies must publish the findings of the evaluation in an annual report. In line with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), HREDD is defined as a standard of conduct, an obligation of means (recital 15).

Unlike Art. 10 (1) GSCDDA, the CSSDD does not oblige companies to document HREDD measures. This, however, seems advisable not only in order to actually fulfil reporting obligations but also to be able to prove that adequate measures have been taken should the company be sued for civil liability or administratively sanctioned. Also, the GSCDDA documentation requirement and respective possibilities for the authorities to request this documentation is a very effective enforcement feature.

Midcap companies referred to in Art. 2 (1) (b) must only conduct targeted HREDD focusing on severe impacts relevant for these sectors (Art. 6 (2)). The rationale behind limiting the due diligence obligations of these (still large companies) is unclear.

The interpretation of the obligations for high impact sectors in Art. 2 (1) (b) can be informed by the OECD sectoral due diligence guidance (recital 22). More generally, in order to interpret the CSDDD and therefore understand the specific content and scope of legal obligations for HREDD, companies can draw upon the United Nations Guiding Principles Reporting Framework as well as the United Nations Guiding Principles Interpretative Guide (recital 26).

HREDD can prove complex, especially when companies have a large number of subsidiaries, contractors, sub-contractors and other business relationships worldwide. In line with the UNGPs, the CSDDD thus gives companies the possibility to prioritize their actions according to “the degree of severity and the likelihood of the adverse impact, […] taking into account the circumstances of the specific case, including characteristics of the economic sector and of the specific business relationship and the company’s influence thereof” (Art. 3 q CSDDD).

Along the value chain

HREDD obligations of the CSDDD cover companies’ own activities, those of subsidiaries under their control as well as operations carried out by direct and indirect established business relationships throughout its upstream and downstream value chain. It therefore extends beyond the entities with whom the company has direct contractual relationships. This goes quite beyond the GSCDDA which only calls for upstream HREDD obligations covering first tiers suppliers (albeit with certain exceptions (see Art. 9 (3) and 5 (4) GSCDDA) which lead to obligations in all related tiers. It is also broader that the LdV which only seems to cover upstream suppliers and sub-contractors with whom the company has “established commercial relationships”.

The CSDDD covers all activities, worldwide, which contribute to the production of their goods or provision of services, including the development of the product or the service or the use or disposal of the product (Art. 3 g), if they are undertaken by entities with whom the company has an “established business relationship”. This is defined as business relationships which are or could become lasting, and which do not represent a negligible or merely ancillary part of the value chain in view of their “intensity or duration” (Art. 3 f). This differs from the UNGPs which call for the HRDD exercise to extend throughout the entire value chain (UNGP 13, allowing for prioritization based on the saliency of the risks, UNGP 24) and which do not contain a restriction to “established business relationships”. It remains to be seen whether or not the concept of an “established business relationship” may have unintended consequences by incentivizing companies to avoid such relationships and instead engage in “superficial” business relationships.

Towards a fairer globalisation

As the Directive’s MHREDD obligations extend beyond Europe, it will likely set new standards even beyond its actual scope of application through the so-called “Brussels effect”. This can open regulatory space to effectively regulate negative externalities on human rights and the environment caused by EU as well as non-EU companies, both in Europe and beyond, and help overcome recurrent issues such as the race to the bottom (deregulate to compete) and the regulatory chill (avoid regulation to avoid investor arbitration). It might push countries outside of Europe to regulate to avoid having a high human rights risk profile which will push away companies obliged to respect human rights under the European rules. As a result – and despite some shortcomings –, the CSDDD has the potential to foster a fairer globalisation by upholding human rights, labour and environmental standards throughout global value chains and facilitate the shift towards a just transition to a sustainable economy.

References

| ↑1 | Schönfelder, in: Grabosch (Hrsg.), Das neue LkSG, 1. Aufl. 2022, § 4, Rn. 9 ff. |

|---|