From Constitutional Crisis to Poisoned Chalice

A letter from London

The national elections to the UK Parliament in Westminster are scheduled for 4 July 2024, and are consequential for the constitution. Having waded through constitutional turmoil during the Scottish independence referendum (2015), the Brexit referendum (2016), landmark Supreme Court cases on the role of Parliament during Brexit in 2017 and 2019, fraught elections in 2017 and 2019 (which bracketed unprecedented parliamentary indecisiveness and insurgency against Government), it is fair to say that the UK constitution was on the ropes by 2020 – the moment Covid-19 entered the ring. What came next was more of a policy than constitutional catastrophe, but the incompetent management of the pandemic and the exposure of unethical behaviour at the centre of government paved the way for the Conservative Party’s free fall from grace in the public eye. In the most notable episode – and what has made ethics and integrity a quasi-constitutional issue for think tanks and the public alike – then Prime Minister Boris Johnson was found to have overseen the holding of boisterous parties at the Number 10 Downing Street while imposing strict stay at home orders on the rest of the country, and was proved to have lied to Parliament about it.

The country has had five Conservative prime ministers since 2010 – Cameron (2010, 2015); May (2016); Johnson (2019); Truss (2022); and Sunak (2022). One might say that the frequent change is an instance of the British constitution working – Cameron, May, Johnson and Truss were outed by the party without elections, as a result of policy failures. It vindicates the comment by ex-Party Leader William Hague that the Conservative Party is ‘an absolute monarchy, moderated by regicide.’ But Labour’s preferred description is ‘chaos’. Their manifesto’s title is one word – Change. The unmistakable anti-constitutionalist element in Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s electoral campaign and large victory in December 2019 provides the important backdrop to developments across four distinct areas of the UK’s political and legal constitution, and to what a likely Labour Government might do about it.

Westminster v Whitehall

Parliament is located in the Palace of Westminster. Whitehall is the adjacent street where one finds the nerve centre of the Government. In theory the former tells the latter what to do. In practice the reverse is the case – but rarely more so than in the last five years.

Following the instability of 2019, the stomping Tory majority returned in the election of December 2019 installed a Government having a belligerent attitude to the House of Commons. It immediately dropped statutory provisions in bills that gave Parliament any say on Brexit negotiations. It passed the Dissolution and Calling of Parliaments Act 2022, which restores Prime Ministerial power to dissolve Parliament and call an election at will, and provides in section 4 that such decisions are non-justiciable in any court of law. The Act thus restores the royal prerogative power, and immunises it from the common law controls that ordinarily apply and were understood to have applied in the Supreme Court’s famous prorogation case.

A greater area of constitutional consternation concerns the use of delegated legislation. It came to a head in the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act 2023, described as ‘hyper-skeletal’ by a key select committee of Parliament. Section 14 confers sweeping ministerial powers to revoke and replace EU law notwithstanding notorious accountability difficulties. The Hansard Society’s ongoing Delegated Legislation Review is the best attempt at a reform programme.

Would Labour row back from these moves? A former political secretary to Tony Blair, John McTernan, was candid in his views expressed in the Financial Times: ‘[T]here have been many moves to strengthen the executive over the past 14 years. Labour should exploit them.’

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++

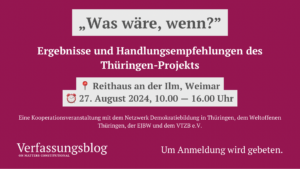

Am 27. August stellen wir in fünf verschiedenen Panels die Handlungsempfehlungen und Ergebnisse unseres Thüringen-Projekts vor. Die Kooperationsveranstaltung mit dem Netzwerk Demokratiebildung in Thüringen, dem Weltoffenen Thüringen, der EJBW und dem VTZB e.V. findet von 10 bis 16 Uhr im Reithaus an der Ilm in Weimar statt.

Bitte melden sie sich bis zum 16. August an. Die Teilnahme ist kostenlos für alle, die die Forschungsarbeit des Thüringen-Projekts mit einer Spende unterstützt haben (bitte mit der derselben E-Mail-Adresse anmelden, die bei der Spende angegeben wurde und dies unter “Sonstiges” vermerken.)

More information here.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

The Territorial Constitution

The UK’s constitution devolves significant power to legislatures and elected governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, but is not federal insofar as the UK Parliament retains unqualified legal and political sovereignty. There has been marked decline in relations between the devolved and UK governments, also in leave-voting Wales.

The Sewel convention, statutorily recognised but not legally binding, is meant to control the UK Parliament’s exercise of plenary law-making authority. It provides that Parliament will ‘not normally’ legislate in devolved matters without the consent of the devolved legislature. But the Westminster Parliament has enacted legislation without such consent on several occasions since the Brexit period. These include most notably the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 and the UK Internal Market Act 2020 (which hastily enacted rules for a post-Brexit UK common market). But it isn’t restricted to big-ticket items. In the first two years of the 2021 Welsh Parliament alone, it refused legislative consent to six Westminster Parliament bills that were anyway enacted into law.

The Labour Party recognises this. The Report of the Labour Commission on the UK’s Future, chaired by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown (the ‘Brown Report’), was conducted under the auspices of the Party and chiefly concerned constitutional reform. It recommended making the legislative consent requirement ‘legally binding’ (p. 103). In the Party’s manifesto, by contrast, this is watered down: it commits to ‘strengthen’ the Sewel Convention by ‘setting out a new memorandum of understanding of how the nations will work together for the common good’ (p. 113). The Labour manifesto more broadly seeks to ‘reset’ intergovernmental relations – a not cosmetic change of tone and style, and which would include a new Council of the Nations and Regions – but is doing so with a kind of ambiguity that, particularly against the more concrete proposals in the Brown Report, might perhaps not be described as constructive.

Human Rights

The Conservative Party committed to ‘scrap the Human Rights Act 1998’ (HRA) in its manifesto of 2015; to maintain it through Brexit but to ‘consider’ it afterwards in 2017; and to ‘update’ it in 2019. The 2024 manifesto has no commitment regarding the HRA at all.

The leading proponent of scrapping the HRA, Dominic Raab MP, became Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Justice in 2021. In 2020, the Party appointed the Independent Human Rights Act Review to investigate the case for repeal and reform of the HRA. Reporting in 2021, to some dismay, it found that no such case existed. Unbowed, Raab introduced his Bill of Rights Bill which would have repealed the HRA and replaced it with a much weaker substitute, leading inevitably to systematic violation of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). However, as the prime mover of the policy, its fortunes fell with those of Raab. A report found he had systematically bullied civil servants across three government departments, and he resigned in April 2023. The bill was withdrawn two months later, the PM lacking the appetite for the inevitable punch up in the House of Lords.

The frontal assault having burned out, a more insidious campaign commenced: one which I call human rights à la carte. Four Acts of the UK Parliament passed since 2021 (and none before then) have contained clauses that disapply or modify the effect of the HRA. Section 3 of the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Act 2024 is the most comprehensive, disapplying nearly the whole of the HRA from decision-making taken under that Act. It leaves in place the court’s power to issue a ‘declaration of incompatibility’, which leaves the laws in effect and is anyway useful political gunpowder for critics of the Strasbourg court or of the ECHR itself. The whole story on human rights exposes the very real limitation of the statutory protection of rights, one which Stephen Gardbaum theorises as the New Commonwealth Model of Constitutionalism. It’s not feeling so constitutional at the moment.

The last Government also significantly curtailed the freedom of assembly and protest through the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 and the Public Order Act 2023. Both statutes confer powers to block protests that create ‘serious disruption’, including noise, but neither defines what it means. They rather confer broad delegated powers on Government to define it – deftly combining the old constitutional problem of unaccountable delegated power with the new one of criminalising public protest. The first batch of ‘serious disruption’ regulations has already been struck down by the High Court for (and predictably) seeking to define ‘serious’ as meaning merely ‘anything more than minor’ (judgment here, press summary here – the decision is on appeal as this comment is published). The UK Parliament’s Joint Committee on Human Rights deemed both laws unnecessary and a presumptive violations of the ECHR (see here and here).

The Labour Party has committed unequivocally in its manifesto to remaining a member of the ECHR, a point reiterated with uncharacteristic lack of equivocation by Sir Keir Starmer in his first televised debate against Prime Minister Sunak on 5 June 2024. This would rationally entail a principled opposition to the à la carte approaches above. But principled opposition is not the same as political commitment. The Shadow Cabinet has already refused to commit to repealing the new public order laws.

The Rule of Law and of International Law

Despite a traditional hostility to clauses that limit judicial review of even inferior tribunals, a number of new statutes unambiguously restrict access to courts. I noted a statutory assertion of non-justiciability over dissolution advice above, but the Illegal Migration Act 2022 contains a breathtaking number of curtailments (see e.g. sections 5, 13, 42-43). Most dramatically, the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Act 2024 deems the Republic of Rwanda a safe country for the purposes of removal from the UK, following a unanimous decision of the Supreme Court that it manifestly wasn’t (R (AAA) v Secretary of State of the Home Department [2023] UKSC 42). The Government maintains that its post-judgment treaty with Rwanda fixes all the problems identified in the Court’s judgment – but this is not the view of Parliament’s International Agreements Committee, nor the UN High Commissioner for Refugees – nor really of anyone who knows anything about it and is being honest. Not even the Prime Minister can block removal on the basis of any intelligence that Rwanda is or has become unsafe, for as long as the Act remains in force. The deeming provision in section 2 applies to courts of law; and also forbids them from using the HRA or any international law to block a removal decision. For good measure, section 5 of the Act reserves to ministers only the power of deciding whether to abide by an interim ruling of the European Court of Human Rights. There are a range of legal challenges before the courts, but few close to the system expect the courts to formally disapply any provision of the Act.

Prime Minister Sunak has made this statutory scheme and the Rwanda policy a centrepiece of his electoral appeal to the people. The Labour Party has committed to repealing this legislation, not on the professed basis of its constitutional defects or cruelty, but because the scheme ‘won’t work’. It also commits to the ‘international rule of law’ in its manifesto, which entails the repeal of the Act. On the other hand, its commitment to extremely low public spending will make it impossible to avert a proper rule of law crisis by restoring the collapsing court estate.

On the whole, there are some grounds for pro-constitutional optimism here, bolstered by the unprecedented fact that Sir Keir Starmer was himself a leading claimant-side human rights barrister. He’s the author of serious books on European and UK human rights law. He’s understandably quiet about these at the moment.

++++++++++Advertisement++++++++

Alle weiteren Infos findest du hier.

++++++++++++++++++++++++

*

The Week on Verfassungsblog

Earlier this month, Biden issued an executive order that effectively bars individuals caught while attempting to cross the Southern border without an appointment from claiming asylum. LENA RIEMER explains why this violates both domestic and international law and what an alternative approach to migration management could look like.

The Loss and Damage Fund, intended to compensate for climate damage in the Global South, was recently a focus of the climate conference in Bonn. However, not only through the fund but also through litigation, plaintiffs from the Global South are seeking compensation payments. ABHIJEET SHRIVASTAVA and RENATUS OTTO FRANZ DERLER examine the instrument of Loss and Damage Litigation from the perspective of the Global South and demonstrate why, despite certain objections, it is an important lever for greater climate justice.

A milestone for queer rights in Namibia: In Friedel Laurentius Dausab vs. The Minister of Justice, the High Court held last week that laws criminalizing same-sex relationships are unconstitutional and invalid. SARTHAK GUPTA explains why the judgment marks a massive leap forward in Namibian anti-discrimination law jurisprudence.

Last week, legal scholars from all over the world met in Freiburg at the ConTrans conference. On the one end of the spectrum, scholars like Wojciech Sadurski advocated for a revolutionary approach, simply dismantling the current Polish Constitutional Tribunal and re-building it from scratch. On the other end stands Adam Bodnar, who stressed the importance of legality in the transition process. LUKE DIMITRIOS SPIEKER argues that the EU law shines a possible way ahead – it can justify disregarding the Tribunal’s decisions and empower ordinary courts to assume the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. Eventually, this would lead to a decentralised constitutional review.

The tone in Switzerland regarding the KlimaSeniorinnen judgment of the European Court of Human Rights is becoming increasingly harsh. There was even a vote in the Federal Assembly to not comply with the ECtHR’s ruling. The climate judgment is considered to be a case of judicial activism. What is the substance of these accusations? Is it really an unlawful interference with the separation of powers? CHARLOTTE BLATTNER explains why the Swiss debate misinterprets the role of the judiciary and why the ECtHR’s ruling is neither undemocratic nor activist (for an English version of the article see here).

When it comes to organ donation, Germany ranks poorly in Europe. However, the discussion about an opt-out solution, like it already exists in Spain, has now gained momentum again. JOSEF FRANZ LINDNER shows what a constitutionally compliant opt-out solution could look like and where there is still room for improvement.

Some might remember “Officer Denny”: the Berlin police officer had to stop operating a TikTok account (with 150,000 followers) – rightly so, the Berlin Administrative Court ruled in March. The decision has now been published. NICOLAS HARDING takes a closer look and sharpens its constitutional arguments. The ruling is not yet final; we will see “Officer Denny” again before the OVG Berlin-Brandenburg.

In its annual report, the German domestic intelligence services disclosed that they are classifying the climate activist group “Ende Gelände” as a “suspected left-wing extremist case”. JAKOB HOHNERLEIN argues that the observation is unlawful. In its 2017 NPD decision, the Federal Constitutional Court refined the concept of a free and democratic basic order. The fact that radical criticism of the system cannot be considered anti-constitutional does not seem to have reached the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution.

FELIX THRUN’s and SIMON MÜLLER’s discussion also addresses the Federal Constitutional Court’s new conception of the liberal democratic basic order. The Higher Administrative Court in Berlin-Brandenburg had to decide whether a position for a legal clerkship can be refused if the applicant actively opposes the constitutional order without committing a criminal offence. The decision follows an inconsistent line of case law on this subject by developing its own set of arguments.

This month, the ECJ confirmed a gender-specific ground for asylum: women who have lived in gender equality for years can be entitled to asylum. With this flexible interpretation of asylum law, the ECJ equips it for future crises – including for climate refugees, analyses SEBASTIAN LOSCH.

FELIX REDA sheds light on legal developments in the area of Chat Control. The draft regulation on preventing and combating child sexual abuse, which was pushed by the Belgian EU presidency, is off the table, at least for the time being. However, based on the experience in the Council, it is clear that an (albeit unqualified) majority of national governments are behind Chat Control in principle. Spain and Ireland had called for even more far-reaching measures. In order to avert Chat Control in the long term, civil society and academia must continue to address the issue.

Party donations can have a significant impact on elections. While Indian party financing laws are rather strict, more and more people are using surrogate advertising on social media platforms to place advertisements on behalf of a political party or candidate without explicitly disclosing their affiliation with that party or candidate. A legal loophole, according to TANMAY DURANI, who suggests ways to close it.

How are legislative conflicts resolved in China, for example, when a piece of legislation violates the Constitution? CHANGHAO WEI explains China‘s new mechanism for “recording and review” and describes a system of institutional correction mechanisms that is likely unknown to many outside of China.

Should one postpone or even cancel the Hungarian Council Presidency in light of Hungary’s continuous breaches of the rule of law? Given the mere informal powers of the Presidency, KAJA KAŹMIERSKA argues against it. She claims that the real damage is rather limited, especially because the Hungarian Presidency takes place just after the European elections. Finally, the Hungarian Presidency may even improve the connection of its citizens with the EU and show the best version of itself.

*

That’s all for this week. Take care and all the best,

the Verfassungsblog Editorial Team

If you would like to receive the weekly editorial as an email, you can subscribe here.