The Commission’s Rule of Law Blueprint for Action: A Missed Opportunity to Fully Confront Legal Hooliganism

In its first Communication entitled “Further strengthening the Rule of Law within the Union” published on 3 April 2019, the Commission offered a useful overview of the state of play while also positively inviting all stakeholders to make concrete proposals so as to enhance the EU’s “rule of law toolbox”. In reply to this invitation, the present authors put together along with other colleagues a submission on behalf of the RECONNECT project which was subsequently published as a RECONNECT Policy Brief. On 17 July 2019, the Commission released a comprehensive follow up Communication in which it sets out multiple “concrete actions for the short and medium term” having first recalled the extent to which the rule of law must be understood as a shared value and a shared responsibility within the EU.

This post will highlight the most innovative actions proposed by the Commission before highlighting what we view as the main weakness of its blueprint: a reluctance to fully accept the reality of rule of law backsliding. In failing to do so, the Commission’s set of actions, while broadly positive, will not stop the ongoing processes of constitutional capture and rule of law rot we have been witnessing in at least the two EU countries which are now subject to Article 7(1) TEU proceedings.

To make matters worse, Ursula von der Leyen, the new President of the Commission, appears oblivious to the reality of a situation where some national authorities are proactively seeking to undermine the rule of law.

Calling for more dialogue while simultaneously normalising the systemic, deliberate and deceitful annihilation of checks and balances we are witnessing in both Poland and Hungary on the ground that “nobody’s perfect” constitute an approach which will only lead to more time being wasted even while rule of law backsliding is spreading to more EU countries and endangering the very survival of the EU legal order.

1. A positive set of concrete proposals

Leaving aside the diagnosis issue for the time being, the Commission should be commended for offering a positive set of concrete proposals. In line with the structure adopted in its April Communication, the Commission’s July Communication offers a number of proposals in three areas: promotion; prevention and enforcement. Rather than describing these proposals in detail (see here for a brief summary), this post will offer a critical overview.

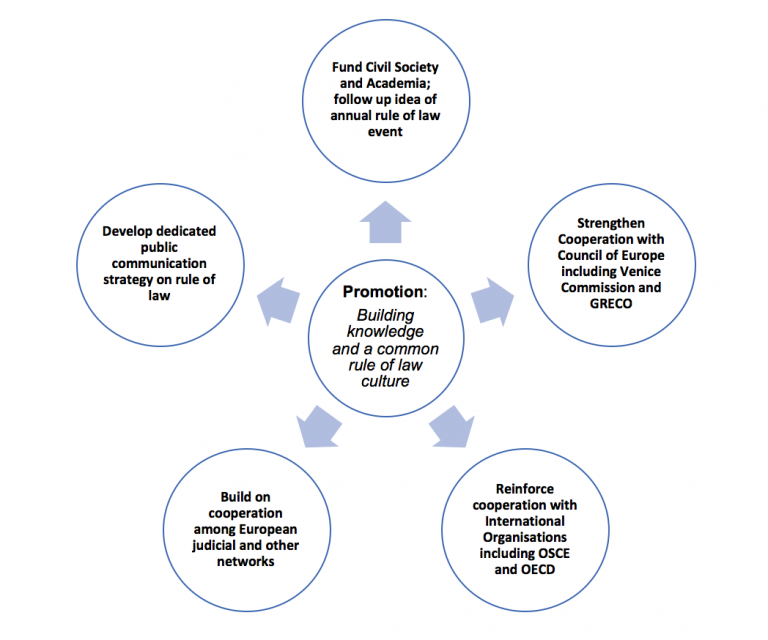

Promotion: Building knowledge and a common rule of law culture

As noted by a RECONNECT colleague of ours, “there is little to criticise” in the “section of the blueprint, which focuses on promoting a rule of law culture in Europe”. We agree and we also welcome each of the Commission’s commitments under this heading.

Regarding some of the Commission’s recommendations, in particular those aimed at national authorities, one may however doubt for instance how realistic it is to expect Hungarian authorities to help “strengthen promotion of the rule of law … including through education and civil society” at a time where the Commission has rightly brought the Hungarian government before the ECJ with respect to its measures targeting the Central European University and NGOs.

Prevention: Cooperation and support to strengthen the rule of law at national level

With respect to prevention-related proposals, the Commission primarily aims to strengthen the EU’s capacity to monitor rule of law related developments at Member State level via a new Rule of Law Review Cycle (RLRC) and a new dedicated dialogue via a network of national contact persons.

Positively, the RLRC will have a broad scope and will cover any potentially negative national development regarding law-making, effective judicial protection, independence and impartiality of the courts, separation of powers, and also the capacity of Member States to fight corruption, as well as media pluralism and elections.

While this is not explicitly stated, the proposed RLRC is based on the paradigm of the normally compliant Member State unwillingly sleep-walking into non-compliance. The main problem with this ‘benevolent Member State paradigm’ is that it does not reflect at all the reality of backsliding Member State as will be explained below.

Another problem concerns the completed network of contact persons. As noted by Justine Stefanelli, “if just one rule of law-deficient member state designates a contact point that has been politically captured, this could render the entire network ineffectual”.

Overall, one may reasonably worry we might end up with the equivalent of pre-accession window-dressing reporting on values. We do not currently lack information about countries where the rule of law is under threat or actively undermined not least due to the regular reports produced by multiple Council of Europe bodies. Viewed in this light, the focus on gathering information could leave one worry the proposed RLRC may end up at this particular juncture distracting the Commission from decisively addressing the most pressing problems at hand. In the enforcement section of the Communication, the Commission however strongly emphasises its readiness to step in when national checks and balances no longer “seem capable of addressing threats to the rule of law”.

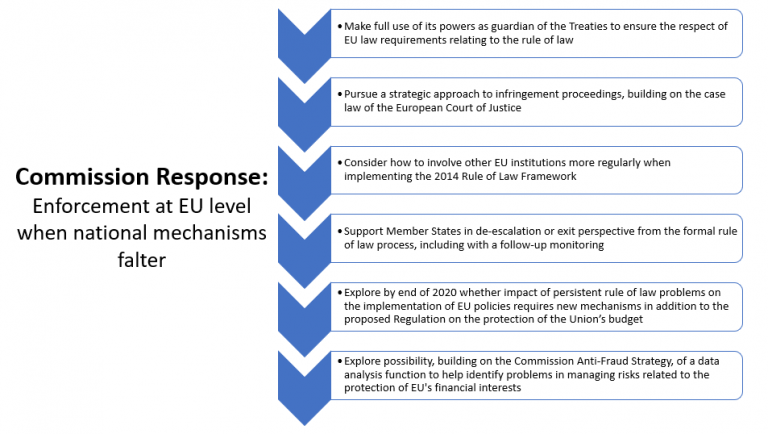

Response: Enforcement at EU level when national mechanisms falter

The Commission’s determination “to bring to the Court of Justice rule of law problems affecting the application of EU law” is obviously welcome but this is also the least one could expect from the Guardian of the Treaties.

Similarly welcome is the Commission’s commitment to “pursue a strategic approach to infringement proceedings related to the rule of law, requesting expedited proceedings and interim measures whenever necessary” but then again one may regret it has taken so long to reach this point.

The Commission and others were warned about what was unfolding in Hungary as early as 2013 in the Tavares report of the European Parliament. It would have been good also to be provided with more details about how the Commission understands “strategic” and “whenever necessary” in this context. That being said, each of the Commission’s commitments is laudable and it is particularly welcome to see the Commission emphasising the link between persistent rule of law problems and the need to protect the EU’s budget.

2. Stopping half way: The Commission’s (mis)diagnosis

The Commission offers the beginning of the right diagnosis at the start of its Communication:

While, in principle, all Member States are considered to respect the rule of law at all times, recent challenges to the rule of law in some Member States have shown that this cannot be taken for granted … Many recent cases with resonance at EU level have centred on the independence of the judicial process. Other examples have concerned weakened constitutional courts, an increasing use of executive ordinances, or repeated attacks from one branch of the state on another. More widely, high-level corruption and abuse of office are linked with situations where political power is seeking to override the rule of law, while attempts to diminish pluralism and weaken essential watchdogs such as civil society and independent media are warning signs for threats to the rule of law

The Commission here comes close to finally accepting that some countries are now led by authorities deliberately seeking to undermine the rule of law with the aim of deceitfully establishing electoral autocracies resulting in the “progressive solidification of factually one-party states”.

Speaking of “attempts to diminish pluralism and weaken essential watchdogs” is however disconnected from the reality of a number of countries as these attempts have already succeeded. To give a single example, Hungary is no longer recognised as a free country by Freedom House and as a consolidated democracy in the latest edition of the Bertelsmann Sustainable Governance Indicators. And this is why we should no longer consider and describe Hungary as a democracy, let alone an illiberal “democracy”, but rather consider it a “pseudo-democracy”.

More problematically, the Commission’s set of actions and proposals previously outlined appear disconnected from these authoritarian developments (more in detail here). To put it differently, while the Commission’s actions and proposals would have been perfect had we been in a “fair weather” situation, sadly, we are not. In at least two EU countries, the rule of law has continued deteriorating even after the activation of the Article 7(1) procedure.

While we can understand why the Communication may be viewed as the wrong place to discuss the ongoing autocratisation of Hungary and Poland, it seems peculiar to claim that the rule of law is a shared value for Europeans – even as evidenced by the results of the April 2019 Eurobarometer survey – while ignoring the extent to which some national officials are increasingly and openly challenging the need to respect the rule of law if not the principle itself. To give two recent examples: last July, the new Hungarian Minister of Justice referred to the rule of law as a vague and elusive term while last August, the Polish President did not merely justify non-compliance with a final, binding ruling of Poland’s Supreme Administrative Court, he openly questioned the validity of the principle of separation of powers and the obligation for the executive to comply with courts’ rulings.

Viewed in this light, the suggestion not to seek “to impose a sanction but to find a solution that protects the rule of law, with cooperation and mutual support at the core – without ruling out an effective, proportionate and dissuasive response as a last resort” is as naïve as it is counterproductive. What does “sanction” mean in this context? A ruling of the ECJ finding a particular “reform” of the national judiciary not to be compatible with EU Law? Can this really be construed as a “sanction”?

In any event, how many times will we have to repeat that dialogue is the autocrat’s best friend. As noted by Daniel Hegedüs, illiberal governments “are not interested in maintaining a constructive rule of law dialogue with the Commission, or if they pretend engagement … they do it to defy the Commission.” And while the EU is engaged in what is in effect often a monologue in practice, the new autocrats have learned they can beat the EU by creating new facts on the ground despite the ongoing “dialogue”.

A better approach would be to accept the reality of rule of law backsliding which requires legal and political actions by all EU institutions not after but during any dialogue phase. Suspending dialogue as soon as a pattern of disloyal cooperation can be evidenced should also be considered.

3. “Nobody’s perfect”

Our concerns about the Commission’s failure to explicitly and specifically address the problem of authorities deliberately and deceitfully pursuing a process of rule of law backsliding have been exacerbated by some of the comments made by the new President of the Commission.

As noted by Dan Kelemen, Ursula von der Leyen has “made several statements indicating the importance of ongoing ‘dialogue,’ of avoiding East-West rifts within the EU, and underlining that on rule of law matters ‘no one is perfect.’ For those who have closely followed the debate over rule of law backsliding in the EU, these are all watchwords for an approach that emphasizes appeasement of backsliding regimes.”

These statements do stand in striking contrast with her commitment – before she was elected by the Parliament – not to “compromise when it comes to respecting the Rule of Law” and to “use our full and comprehensive toolbox at European level” so as “to defend the Rule of Law wherever it is attacked”.

Stating subsequently that no one is perfect when it comes to the rule of law suggests quite a different approach if not a complete lack of understanding of what has been happening on the ground as it essentially normalises the deliberate transformation of a democratic system based of the rule of law into an autocratic regime and excuses behaviours such as:

- Dismissal of court presidents and vice-presidents “without any specific criteria, without justification and without judicial review”;

- Refusal to “publish and implement fully” rulings of the national constitutional court;

- Refusal to comply with a Commission’s recommendation not to appoint an acting president of the national constitutional court in obvious breach of the national constitution;

- Refusal to comply with an interim order of the ECJ;

- Refusal to comply with an interim order of the national supreme administrative court;

- Refusal to comply with a final ruling of the national supreme administrative court by hiding behind a patently unlawful decision of the captured office of the supposedly independent data protection authority?

- Threats of disciplinary action against a Supreme Court judge for complying with an ECJ order;

- Threat to not comply with ECJ ruling depending on its content;

- Official instruction to ignore the national supreme court’s ruling;

- Provision of misleading information to the Council of the EU regarding disciplinary proceedings against national judges exercising their right to refer preliminary ruling question to the ECJ;

- Attempt to mislead the ECJ according to the ECJ itself regarding the real objective underlying a national legislation lowering the retirement age of judges of the supreme court;

- Public allegation made by the President that a ruling of the national constitutional court violated the national constitution with the same President having played a leading role in creating a constitutional crisis by violating the national constitution to ensure the political capture of the same court;

- Promotion of a “vision” where judges are expected to be always “on the side of the state” with the conduct of judges being described as “dangerous” when they “turn against the legislative and executive authorities”;

- Conspiracy led by top officials of the Ministry of Justice and taking the form of provision of confidential and/or personal information to an anonymous Twitter account so as to bully and scare judges into submission or the organisation of a smear campaign against the President of the Supreme Court, all the while the government is assuring EU institutions that national authorities “have never undermined the legitimacy of the Supreme Court, ordinary courts or judges – individually or collectively”.

But “nobody’s perfect”, right?

This post was previously posted on the RECONNECT blog and is reposted here with kind permission by the authors.

Maybe our problems with the rule of law in Europe has also something to do with its (sometimes bad) quality?

[…] Indeed, as many experts have noted, dialogue is the autocrat’s best friend, as autocrats “have learned they can beat the EU by creating new facts on the ground despite the ongoing ‘dialogu….” Calling for more dialogue with autocrats in the hope of preventing rule of law backsliding is […]

[…] Indeed, as many experts have noted, dialogue is the autocrat’s best friend, as autocrats “have learned they can beat the EU by creating new facts on the ground despite the ongoing ‘dialogu….” Calling for more dialogue with autocrats in the hope of preventing rule of law backsliding is […]